Jens Nordvig, one of the hottest prognosticators in finance, will sell anyone his secret sauce for winning trades for $30,000 a year.

But if you want unfettered access to his best ideas and personal touch—the kind that the deep-pocketed hedge funds covet—be prepared to shell out about 20 times more.

That two-pronged approach to research, off-limits (at least officially) at Wall Street banks, captures one of the most striking shifts in finance today: the rise of a class system where entire businesses cater to only the highest-paying clients. Of course, haves and have-nots have long existed in the world of finance. But the widening gap within Wall Street itself, between what the privileged few and most others get, is creating a new financial elite—what amounts to the 1 percent of the 1 percent.

And if you’re not part of the 0.01 percent, the next best thing is to sell to it.

“Investors either get personalized advice from someone they really trust, or it’s the data tools, good robots—and the price of those two things are different,” the 42-year-old Dane explained from his WeWork office in Manhattan’s Flatiron district one recent afternoon.

For Nordvig, who left Nomura Holdings Inc. in January after five years as Wall Street’s top-ranked currency strategist, it meant leveraging that standing to build his firm, Exante Data, around a rarefied group of the brightest hedge-fund names— and the money they dole out.

Exante counts Key Square, founded by George Soros protege Scott Bessent, and Adam Levinson’s Graticule, a Singapore-based firm spun out of Fortress Investment Group, among its clients, according to conversations with investors and people familiar with the matter. Graticule didn’t reply to requests for comment.

Nordvig declined to identify specific firms, but says there are just “five to seven” large institutions, whose fees covered most of his startup costs. And by design, he isn’t accepting any new business. That’s because while Exante’s six employees are focused on its analytics rollout, Nordvig devotes the majority of his time advising his marquee customers.

He’s in touch with them on an almost daily basis and is just a phone call or instant message away—any time, 24/7. His research is tailor-made to suit each one’s needs and Nordvig says he’ll often spend hours at a time with a single firm debating macroeconomic policy and trade strategies.

In late July, Nordvig was up until midnight defending his high-stakes call to a hedge-fund client in Asia that the Bank of Japan would stand pat, rather than announce a new set of aggressive stimulus measures as everyone expected. (He dissuaded the firm from shorting the yen, which proved to be prescient as the Japanese currency surged following the non-event.)

“At banks, it’s mass production. It’s Target versus Hermès.”

So far, his backers like what they see.

“Jens is one of the great thinkers in the market,” said Key Square’s Bessent, who oversaw Soros’ personal fortune before starting his own billion-dollar macro fund this year. “Part of what we did was we got him to control his number of clients. At banks, it’s mass production. It’s Target versus Hermès.”

Nordvig isn’t shy about what he brings to the table. Prior to his years at Nomura, he spent almost a decade at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., where he rose to become co-head of global currency research and made his name with bold calls and savvy analysis. In between, he did a brief stint at Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates. And Nordvig brushes off the perception among both admirers and critics that he can, at times, be just a bit too brazen in promoting himself. To him, it’s just part of the cutthroat nature of finance.

“I have a track record of being quite detail-oriented, precise in my analysis and also able to develop new frameworks for thinking about things, and at the same time being quite pragmatic,” he said. “I’ve set up the advisory business so that the people I deal with are some of the biggest macro investors in the world, and I know their interests fit with how I think.”

Whatever the case, there is little doubt the appetite for bespoke research like Nordvig’s is growing. Banks are slashing costs, cutting jobs and abandoning their ambitions to be all things to all customers in the face of a slew of regulations over issues like selective access and excessive risk-taking. An industry-wide slump in revenue since the financial crisis has also prompted bank executives to rethink the value of the commission-based model, where investment research is offered for free in return for trade orders.

Many firms have eliminated analysts as they scale back research spending—making personalized service and attention all the more valuable. Some like Citigroup Inc. and Morgan Stanley have drawn up preferred client lists with code names such as “Focus Five” and “supercore” for top clients.

“It’s a changing landscape,” said Matthew Feldmann, a consultant at Scepter Partners, a multi-family office, and a former money manager at Citadel and Brevan Howard. “People like Jens have found a niche area where all you need is a few wealthy individual customers.”

Perhaps just as important is the proliferation of automated trading strategies and machine-driven data mining, which has replaced many traditional roles that used to exist on Wall Street (not to mention made it harder for hedge funds to outperform as technology makes financial data almost ubiquitous).

Nordvig’s old job at Goldman Sachs exemplified that bygone era. As recently as 2007, he’d stand in the middle of the trading floor with mic in hand on the first Friday of every month, just before the 8:30 a.m. payrolls report. His task? Shout out his immediate take. If the U.S. added more jobs than expected, he’d cry “buy dollar-yen!” and within seconds, Goldman Sachs’s traders would hit the button on their keyboards to put in the order.

“We used to be able to make so much money by just being fast,” he said. Yet today, it’s all done by robots.

Amid the upheaval, Nordvig is confident his experience and smarts will ensure his high-priced advice remains in demand. But he’s not taking any chances.

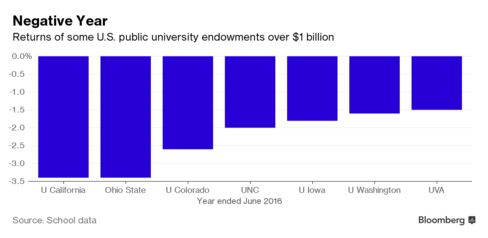

After years of lackluster returns and faced with the biggest withdrawals since the financial crisis, hedge funds are looking for any edge they can find. These days, that often comes from the world of quantitative analysis. Even legendary names like Paul Tudor Jones, who made their fortunes the old-fashioned way, are hiring a bevy of programmers and mathematicians to build out more sophisticated, computer-driven strategies.

But not everybody has the research budgets to hire scores of Ph.D.s or pay for Nordvig’s white-glove service. That’s where the “data” in Exante Data comes in (Exante is derived from “ex ante,” Latin for “before the event”). Plenty of research superstars have decamped from Wall Street to set up boutique advisory firms, but Exante’s two-tier model is rare. Once the data business is fully up and running, Nordvig promises to give mere mortals on Wall Street the same type of data-mining tools once available only to the biggest quant shops.

Nordvig says he has one overriding advantage: he simply understands markets better.

Yet competition on the data front is heating up. Scores of startups are already scraping data and turning the information into actionable ideas. Goldman Sachs is the biggest investor in Kensho Technologies Inc., which analyzes historical trading patterns to predict how assets react to events like policy meetings and economic releases. An outfit called SpaceKnow Inc. uses satellite images of factories to gauge economic activity in export-oriented countries like China.

Nordvig, in his typical cocksure manner, says he has one overriding advantage: he simply understands markets better.

In coming months, Exante will launch its first data product for the masses. According to Nordvig, his data scientists have come up with a complex algorithm that precisely estimates how much the yuan exchange rate is influenced by China’s buying or selling of dollars, on a daily basis.

There’s nothing publicly available that comes close to measuring intervention in such detail. But Nordvig says his algo succeeds because it can capture anomalies in yuan trading, like a sudden widening in bid-ask spreads, and then compare the data against freely-traded markets in big financial centers.

While the tool can’t yet gauge intervention in offshore yuan and currency forwards, his backtested results show it closely tracks less frequently released official figures. And knowing beforehand can make a huge difference. Case in point: In August 2015, the People’s Bank of China unexpectedly engineered a weakening of the yuan, which blindsided investors and sent financial markets worldwide into a tailspin.

“This is about knowing what topics are important to the clients you serve,” Nordvig said.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2016-09-15/wall-street-s-0-01-the-guru-who-only-talks-to-hedge-fund-elite