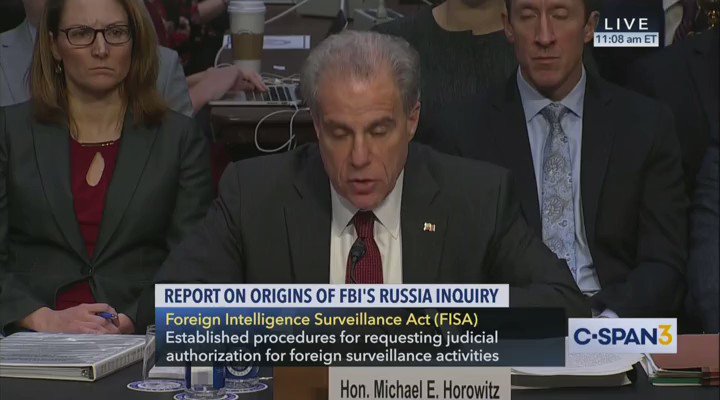

Update: IG Horowitz told Congressional investigators on Wednesday that FBI officials should have seriously reconsidered their surveillance efforts on former Trump campaign aide Carter Page in early 2017, when information they gathered cast significant doubt on their legal justification to surveil him, according to Bloomberg.

Horowitz also said that the FBI misled the FISA court in order to keep spying on Page.

"I don’t think the Department of Justice fairly treated these FISAs, and he was on the receiving end of them," he said.

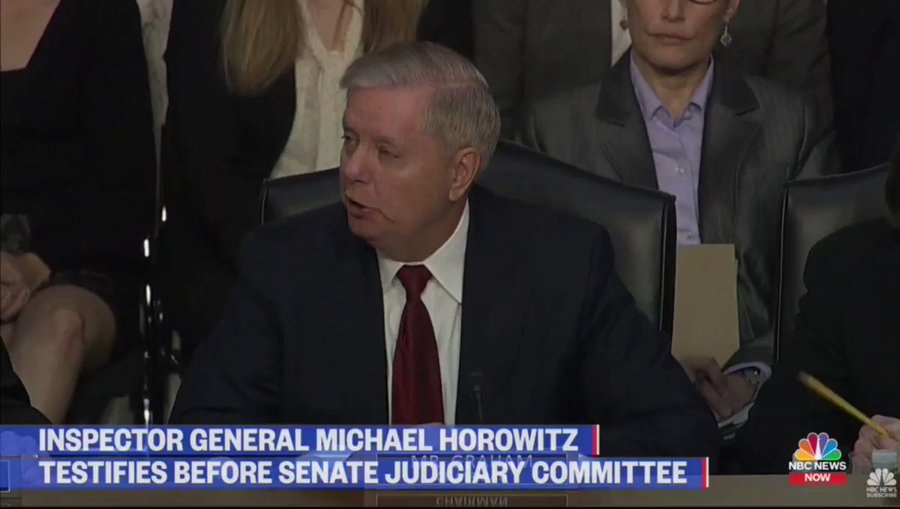

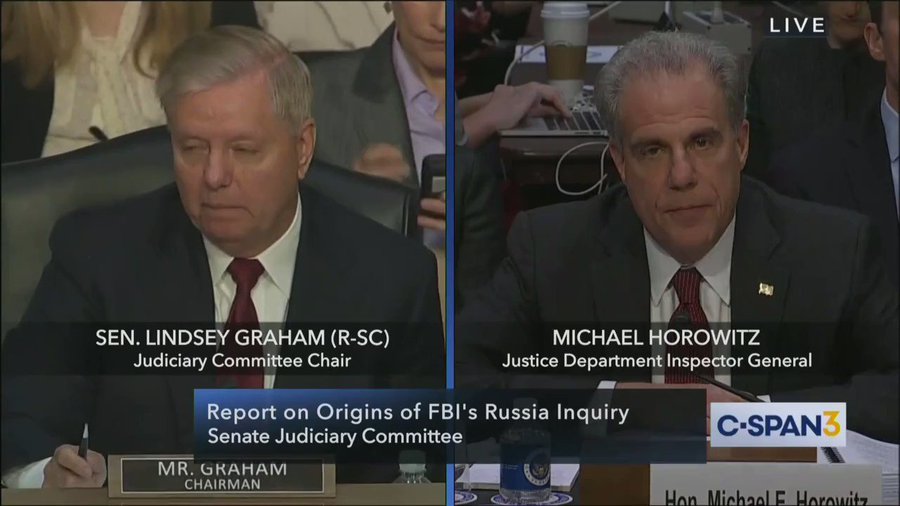

Sen. Lindsey Graham on FBI surveilling the Trump campaign: “Let’s put it this way, if you don’t have a legal foundation to surveil somebody and you keep doing it is that bad?”

IG Michael Horowitz: “Absolutely.”

Graham: ”Is that spying?”

Horowitz: “It’s illegal surveillance.”

2,750 people are talking about this

What (conveniently) no one is saying about IG Horowitz’s testimony today is that while he said in the report there no bias as to how the investigation started (low threshold)... based on everything else he said there is an insane amount of bias from that point forward.

8,531 people are talking about this

At one point Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) asks, "A lawyer at the FBI creates fraudulent evidence, alters an email that is in turn used as the basis for a sworn statement to the court that the court relies on. Am I stating that accurately?" to which Horowitz responds: "That's correct. That's what occurred."

This exchange. Staggering.

Cruz: “A lawyer at the FBI creates fraudulent evidence, alters an email that is in turn used as the basis for a sworn statement to the court that the court relies on. Am I stating that accurately?"

Horowitz: "That's correct. That's what occurred"

10.7K people are talking about this

Then there's this gem:

Oof.

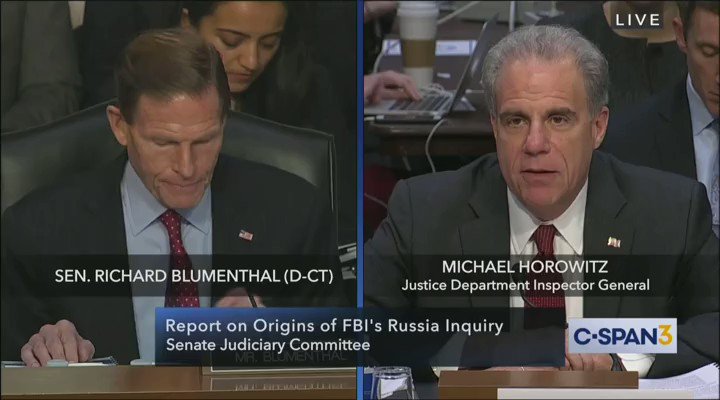

Blumenthal: "[FISAs] are renewed because they are producing useful information, correct?"

IG: "Or they should be producing useful information."

Blumenthal: "...they were producing useful information, correct?"

IG: "I'm not sure that's entirely correct."

2,971 people are talking about this

***

While every painful second of every individual's testimony during the impeachment hearings was relayed and narrative-managed by the mainstream media (and still failed to increase public awareness, let alone support for the Democrats' plan), interested viewers were hard-pressed to find Justice Department Inspector General Michael Horowitz testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee (on his findings regarding alleged surveillance abuse during the 2016 election) anywhere on the mainstream.

There are plenty of nuggets to enjoy - if you can find a live stream (here) - but this one was particularly noteworthy.

A day after a smug-sounding James Comey tweeted that the IG's report vindicated him:

“So it was all lies. No treason. No spying on the campaign. No tapping Trumps wires. It was just good people trying to protect America.”

Howoritz, in one short sentence, destroyed the former FBI Director's credibility by explaining simply...

"I think the activities we found here don't vindicate anybody who touched this FISA."

BOOM inspector-general smacks Comey right in his self-righteous mouth. Nobody was Vindicated that touched this issue and investigation

62 people are talking about this

As Mr. Horowitz wrote in his report, he lays the blame at the top (cough Comey cough):

“We are deeply concerned that so many basic and fundamental errors were made by three separate, hand-picked investigative teams; on one of the most sensitive FBI investigations; after the matter had been briefed to the highest levels within the FBI; even though the information sought through use of FISA authority related so closely to an ongoing presidential campaign; and even though those involved with the investigation knew that their actions were likely to be subjected to close scrutiny. We believe this circumstance reflects a failure not just by those who prepared the FISA applications, but also by the managers and supervisors in the [investigation’s] chain of command, including FBI senior officials who were briefed as the investigation progressed.”

As WSJ noted ironically, Mr. Comey’s memoir, “A Higher Loyalty,” relates how as FBI director he kept on his desk a copy of the October 1963 memo from J. Edgar Hoover asking for permission to wiretap Martin Luther King. He claims he did so to help ensure the bureau would never forget how a “legitimate counterintelligence mission . . . morphed into an unchecked, vicious campaign of harassment and extralegal attack.”

Mr. Horowitz’s findings about what was done under Mr. Comey’s leadership suggest there’s still a need for such a reminder.

Finally, in case the entire "Russia, Russia, Russia" narrative of the last three years has just become too much for you, here is Senator Lindsay Graham, in two short minutes explaining the whole farce so clearly that we dare even the most dyed in the wool NeverTrumper to explain how this was not a clear act of sedition...

I would like someone to explain how this egregious FBI conduct happens for any reason-

other than a deep state bureaucrat’s desire to keep the pressure on the Trump campaign out of political malice twitter.com/politicalshort…

625 people are talking about this

Of course, as Sen. Marsha Blackburn exzclaimed on Twitter, "The fact that CNN and MSNBC refused to run Lindsey Graham's opening statement uninterrupted, but is now carrying Senator Feinstein's, is proof that political bias is not isolated to the FBI."

Update: Horowitz says the Carter Page FISA warrant was based "entirely" on the debunked Steele dossier...

BOMBSHELL:

Inspector Horowitz admits that the warrant to spy on the Trump campaign was based "entirely" on information from the debunked Steele Dossier.

The media continues to deny this fact!

7,134 people are talking about this

What (conveniently) no one is saying about IG Horowitz’s testimony today is that while he said in the report there no bias as to how the investigation started (low threshold)... based on everything else he said there is an insane amount of bias from that point forward.

8,531 people are talking about this

Q

Q