Earlier today Trump declared that Sunday would be a national day of prayer.

With Americans having far bigger concerns on their minds, we doubt many will have time for prayer today, although there is one person who certain could do with some divine assistance: Fed chair Jerome Powell.

And there is a specific reason for that... or rather 12 trillion reasons.

But first, let's back up to a post we write back in October 2009 explaining how the Fed's emergency response during the financial crisis - which included credit facilities backed by corporate bonds and even stocks, all the way to unlimited FX swap lines with foreign central banks - was first and foremost in response to a massive dollar margin call that resulted in the aftermath of the Lehman and AIG collapse as conventional cross-border funding pathways froze up, forcing the Fed to step in and flood the world with dollars to avoid a catastrophic surge in the dollar as the entire world scrambled to obtain the world's reserve currency.

Back then the BIS published a paper titled "The US dollar shortage in global banking and the international policy response" which explained how then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in essence bailed out the entire developed world, which was facing an unprecedented dollar shortage crisis due to the sudden deflationary shockwave unleashed by the financial crisis, which also ground the global economy, and conventional dollar funding pathways to a halt while heightened counterparty risk after Lehman's collapse and liquidity concerns compromised short-term interbank funding, resulting in a lock of shadow banking conduits and money market funds "breaking the buck." In short: an unprecedented crisis as a result of a global dollar margin call.

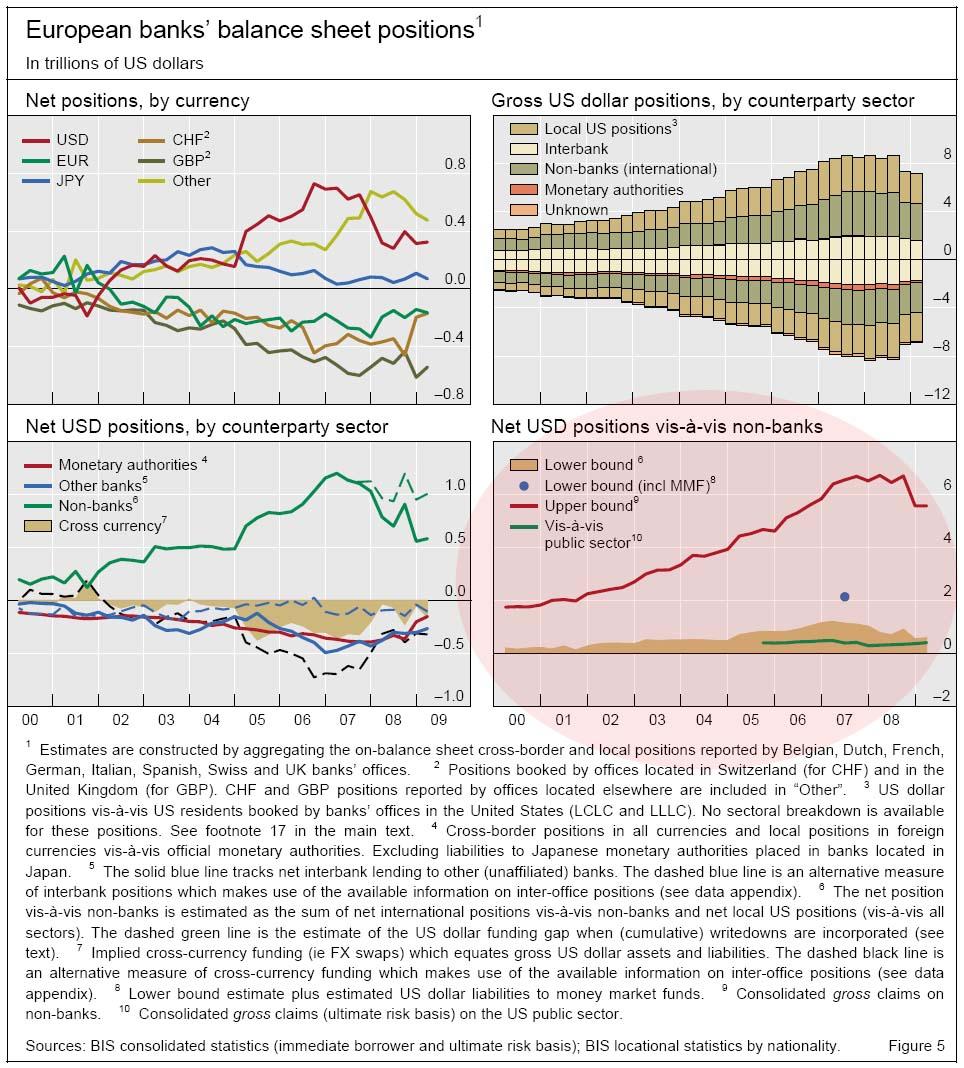

This is how the BIS quantified the peak dollar shortage at the heights of the financial crisis:

... European banks’ US dollar investments in nonbanks were subject to considerable funding risk at the onset of the crisis. The net US dollar book, aggregated across the major European banking systems, is portrayed in Figure 5 (bottom left panel), with the non-bank component tracked by the green line. By this measure, the major European banks’ US dollar funding gap had reached $1.0–1.2 trillion by mid-2007. Until the onset of the crisis, European banks had met this need by tapping the interbank market ($432 billion) and by borrowing from central banks ($386 billion), and used FX swaps ($315 billion) to convert (primarily) domestic currency funding into dollars. If we assume that these banks’ liabilities to money market funds (roughly $1 trillion, Baba et al (2009)) are also short-term liabilities, then the estimate of their US dollar funding gap in mid-2007 would be $2.0–2.2 trillion. Were all liabilities to non-banks treated as short-term funding, the upper-bound estimate would be $6.5 trillion (Figure 5, bottom right panel).

Had the Fed not stepped in with a barrage of liquidity-providing instruments and facilities, the rest of the world would have simply collapsed as the $6.5 trillion dollar funding gap closed in on itself, causing an indiscriminate sell off of all dollar denominated assets. It also triggered the first ever launch of virtually unlimited dollar swap lines between the Fed and all other central banks:

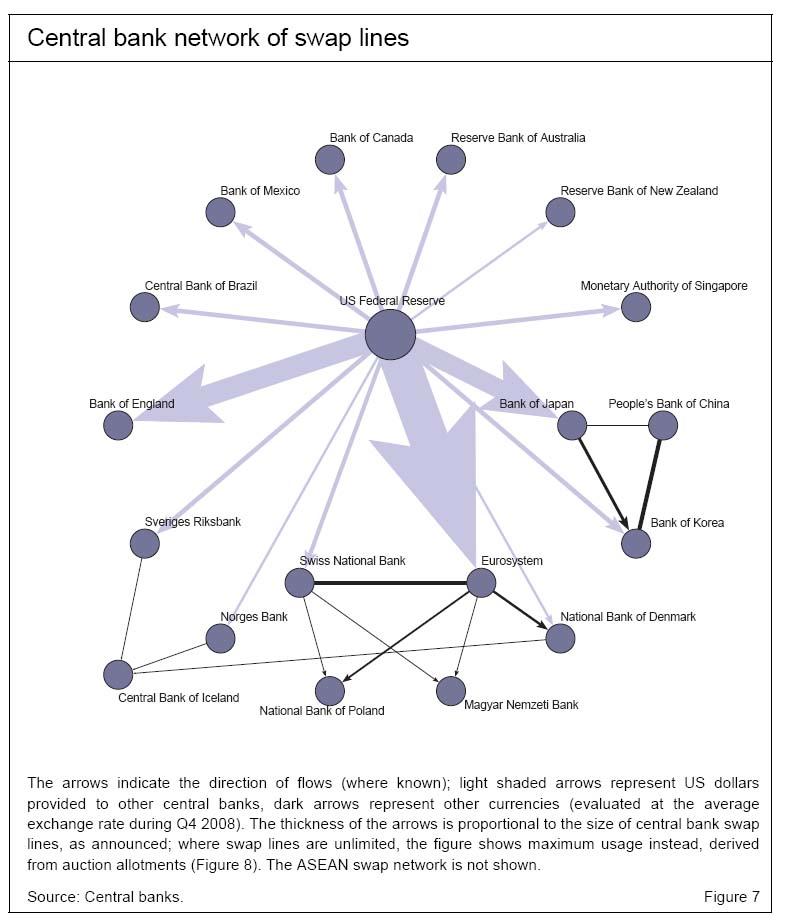

The severity of the US dollar shortage among banks outside the United States called for an international policy response. While European central banks adopted measures to alleviate banks’ funding pressures in their domestic currencies, they could not provide sufficient US dollar liquidity. Thus they entered into temporary reciprocal currency arrangements (swap lines) with the Federal Reserve in order to channel US dollars to banks in their respective jurisdictions (Figure 7). Swap lines with the ECB and the Swiss National Bank were announced as early as December 2007. Following the failure of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, however, the existing swap lines were doubled in size, and new lines were arranged with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan, bringing the swap lines total to $247 billion. As the funding disruptions spread to banks around the world, swap arrangements were extended across continents to central banks in Australia and New Zealand, Scandinavia, and several countries in Asia and Latin America, forming a global network (Figure 7). Various central banks also entered regional swap arrangements to distribute their respective currencies across borders.

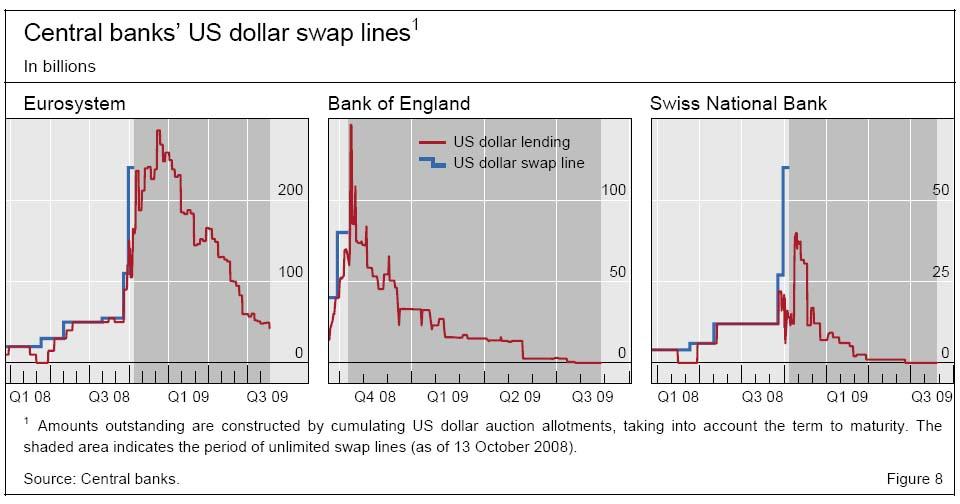

The newly created swap lines which served as a "letter of credit" underwritten by the entity that prints the US currency...

... soared in usage in the early days of the financial crisis, and were critical to contain a far greater liquidation cascade.

Why do we bring all this ancient history up? For two reasons.

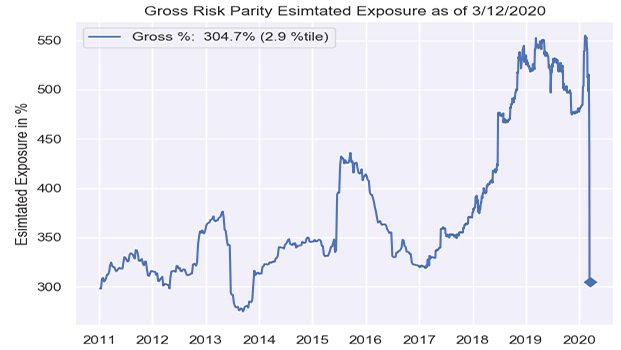

First, it may come as a shock to some but ever since the financial crisis nothing has been actually fixed, and instead the Fed stepped in at every market stress event to inject more liquidity, aiding the issuance of even more debt, and kicking the can while while helping mask the symptoms of the crisis, only made the underlying financial instability even more acute. Meanwhile conventional wisdom that the US banking system was rendered more stable now are dead wrong, with the public and countless financial professionals fooled by the nearly two trillion in excess reserves (we all saw what happened when this number dropped to a precarious "low" of "only" $1.3 trillion in September of 2019) injected by the Fed in recent years. All this liquidity upon liquidity has only made the system that much more reliant on the Fed's constant bailouts and liquidity injections.

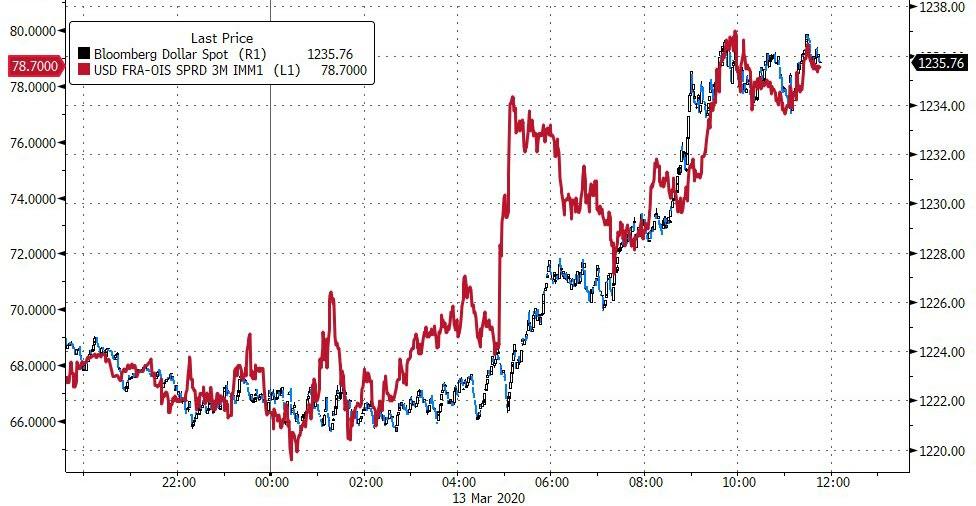

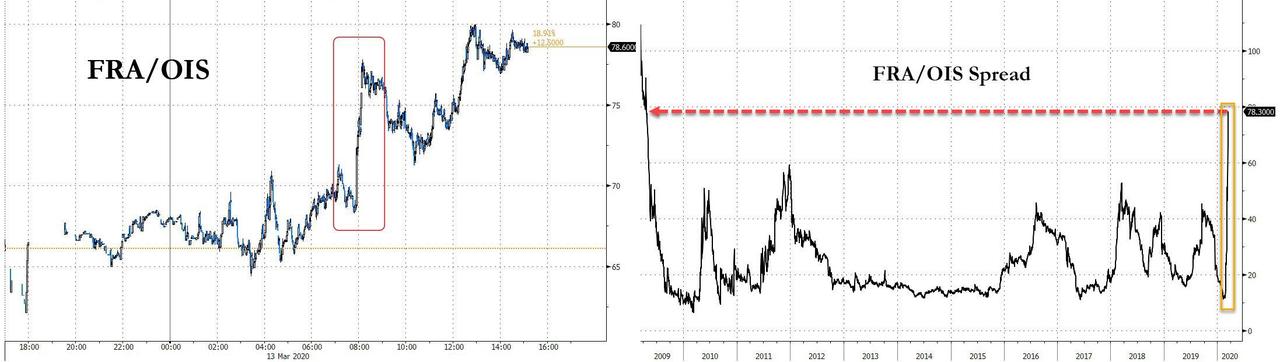

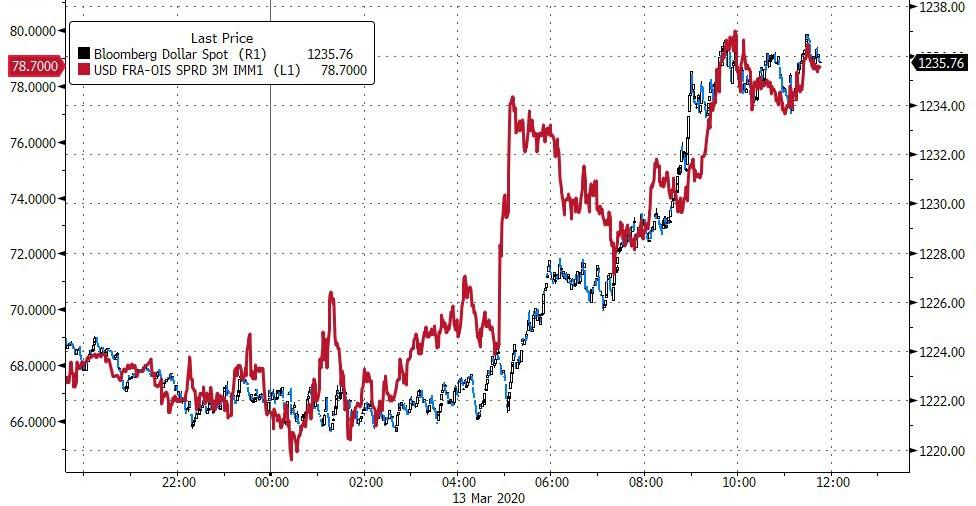

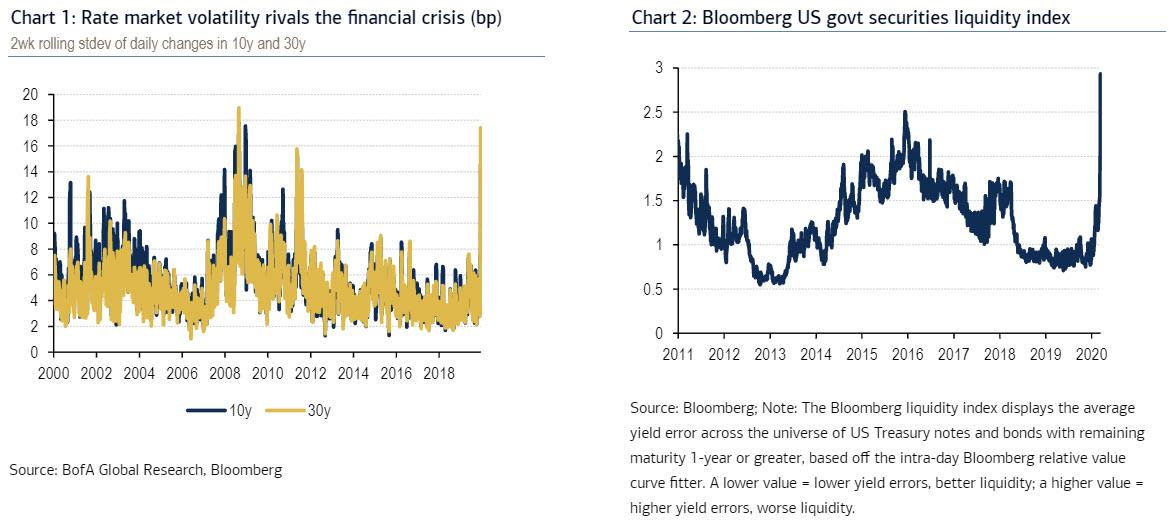

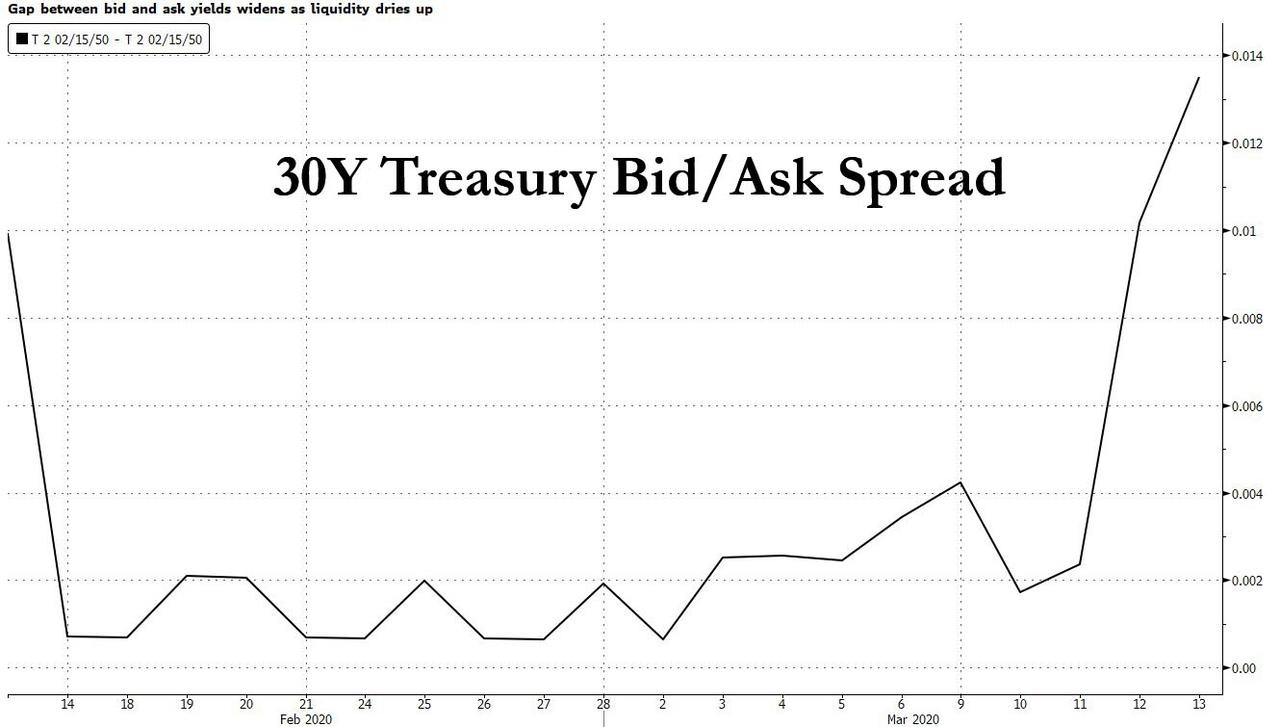

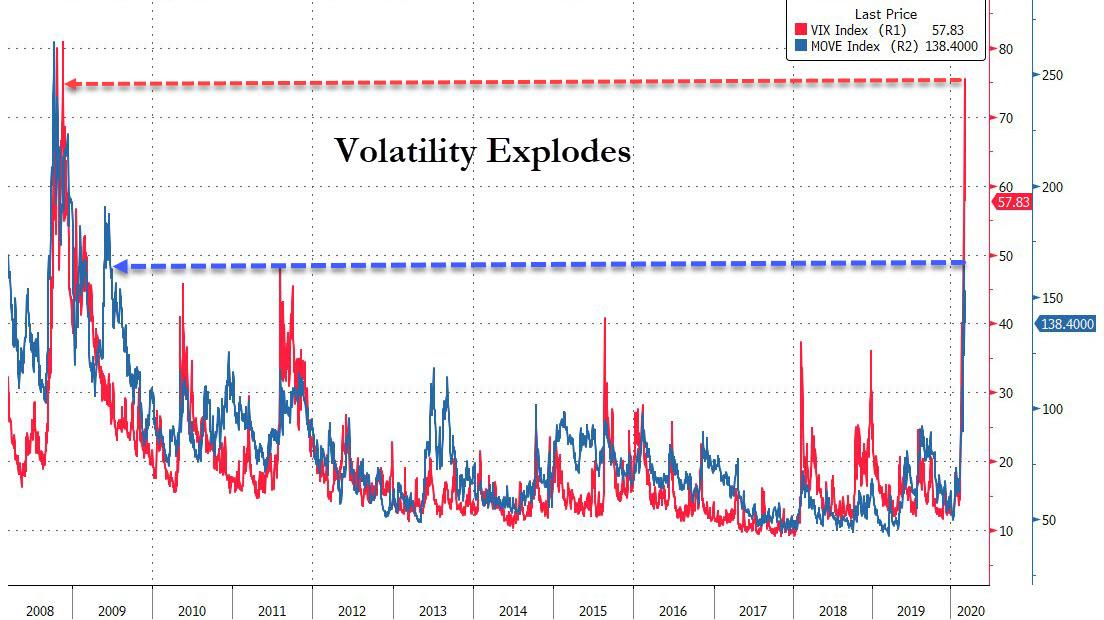

Ssecond, as the events of last week so ominously demonstrated, the dollar shortage is back with a vengeance, as confirmed by last week's concurrent surge in both the Bloomberg Dollar index and the FRA/OIS spread, a closely followed indicator of interbank dollar funding availability.

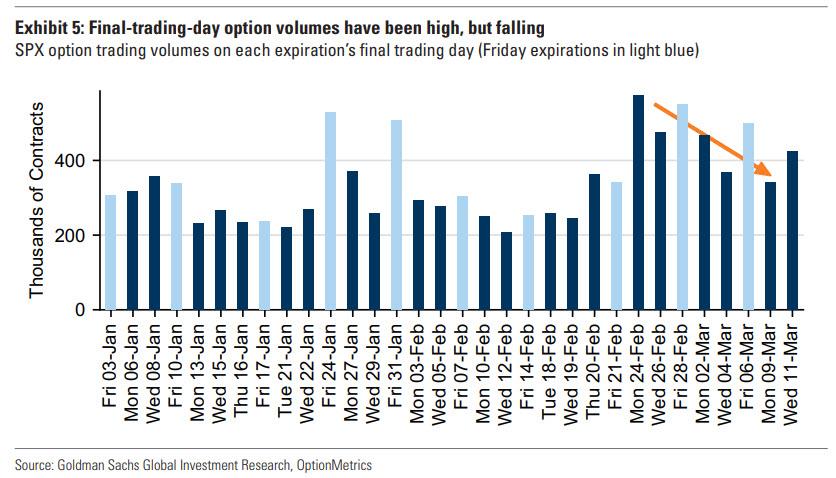

Indeed, as of Friday, and following a rollout of various "bazooka" interventions by the Fed including a massive $5 trillion repo facility and the launch of QE5, as well as an emergency six POMO operations on Friday to unlock the freezing Treasury market which failed to boost risk sentiment, the FRA/OIS not only failed to respond but surged to the highest level since the financial crisis.

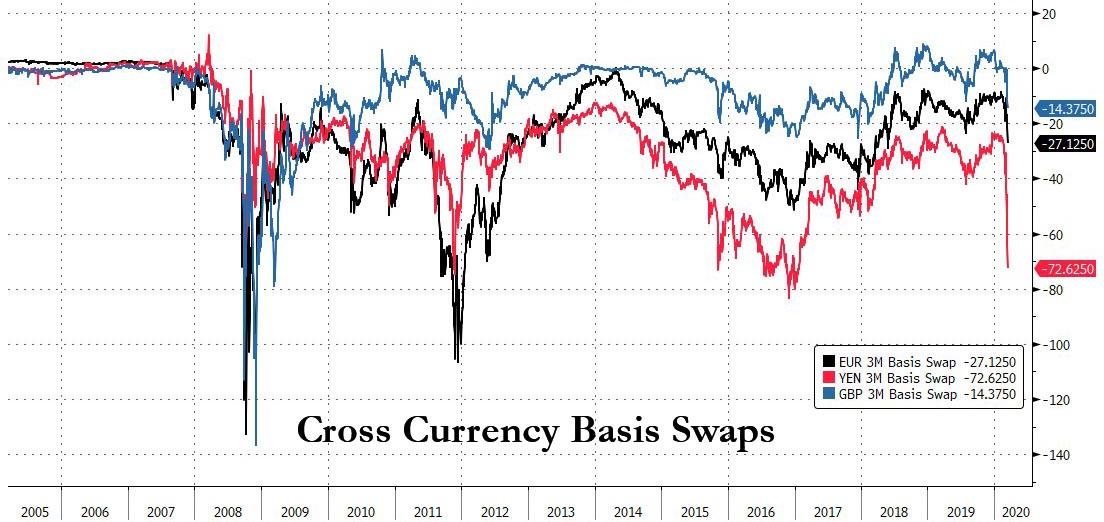

At the same time cross-currency basis swaps - especially for Japan - are screaming dollar shortage...

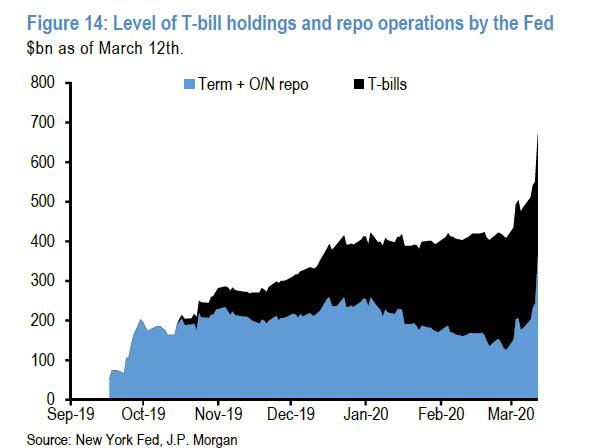

... which is not worse only thanks to the trillions in excess dollars already sloshing in the system as well as last week's emergency liquidity injections which boosted the Fed's balance sheet by over $200 billion in just a few days in the form of expanded repos and quantitative easing.

... which is not worse only thanks to the trillions in excess dollars already sloshing in the system as well as last week's emergency liquidity injections which boosted the Fed's balance sheet by over $200 billion in just a few days in the form of expanded repos and quantitative easing.

And yet - as the market's response to the Fed's bazooka announcement demonstrated - it does not appear to be enough.

Why?

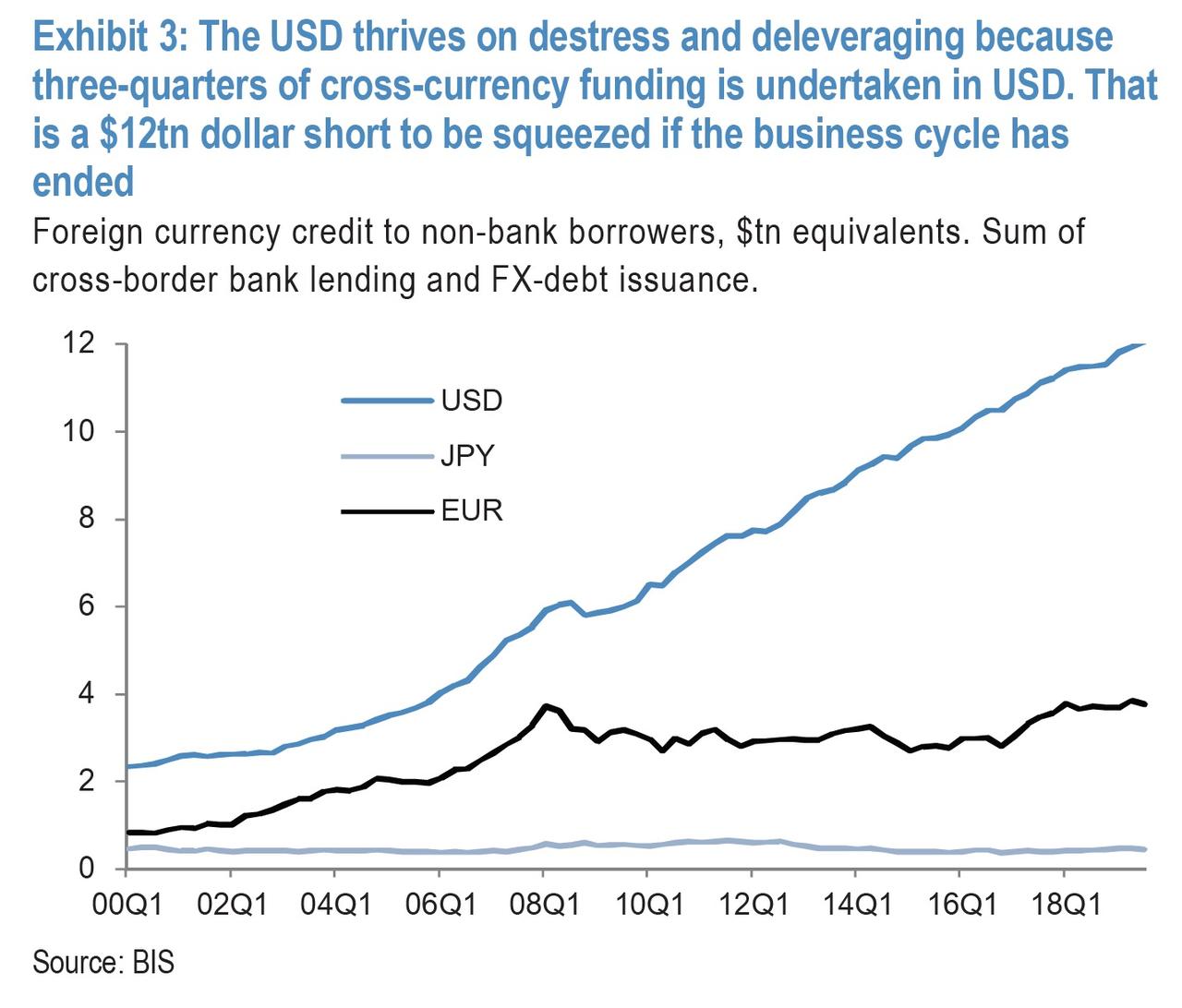

Because, and going back to the original topic of a massive dollar margin call, there is now - in JPMorgan's calculations - a global dollar short that has doubled since the financial crisis and was $12 trillion as of this moment, some 60% of US GDP.

So what can the Fed do? For one possible answer we go to Zoltan Pozsar who last week laid out precisely why the coronavirus pandemic (and subsequent oil crisis) would led to a historic run on the dollar (as he so aptly put it "the supply chains is a payment chain in reverse... and so an abrupt halt in production can quickly lead to missed payments elsewhere"), and concluded that to offset the dollar scramble, the Fed would need to "combine rate cuts with open liquidity lines that include a pledge to use the swap lines, an uncapped repo facility and QE if necessary."

So far the Fed has already launched stealth QE, which will likely transform into an official, full-blown QE5 this week when the FOMC meets, and all that's missing are swap lines and an uncapped standing repo facility, both of which cross beyond the purely monetary realm and have political implications. Whether those are also announced today will depend on if the Fed will pursue another intermediate step first, in the form of a Commercial Paper facility, which Bank of America believes will be unveiled in just a few hours.