While the use of hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 has dominated headlines for weeks, a new method of treatment developed by Johns Hopkins Hospital has just been given special approval by the FDA to be fast-tracked.

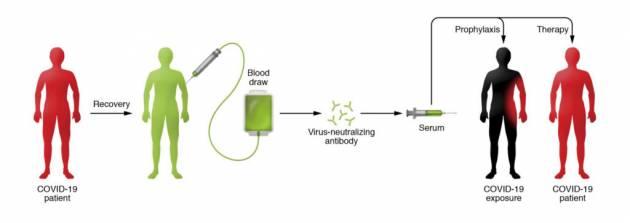

Known as convalescent serum therapy, the antibody-rich blood plasma from COVID-19 survivors is drawn, bagged, and given to critically ill patients.

While the FDA began allowing limited use of the therapy on March 24 for hospitals in Houston and New York City (with an "expanded access program" pending), Johns Hopkins is concurrently developing the therapy with the goal of preventing otherwise healthy front-line medical staff from getting sick. The university is awaiting FDA approval for a second clinical trial on patients who are slightly to moderately ill to see if it can reduce or eliminate COVID-19.

Under the leadership of immunologist Arturo Casadevall, the Johns Hopkins team is collaborating with physicians and scientists around the country to establish a network of at least 40 hospitals and blood banks in 20 states for the collection, isolation, and processing of blood plasma.

More via Johns Hopkins (emphasis ours):

People who recover from an infection develop antibodies that circulate in the blood and can neutralize the pathogen. Researchers hope to use the technique to treat critically ill COVID-19 patients and boost the immune systems of health care providers and first responders. Currently there are no proven drug therapies or effective vaccines for treating the novel coronavirus.

"At the end of January, I knew this disease was going to get out of China, and I knew there was a huge history of the use of plasma and serum in the 20th century," says Casadevall, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of molecular microbiology and immunology and infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and School of Medicine. "This [medical effort] has become a juggernaut… We're racing to deploy this."

Thousands of survivors might soon line up to donate their antibody-rich plasma, according to physicians. But that's only if early promising studies on the therapy done in China are confirmed by U.S. trials that show "dramatic effects and improvements" in patients, according to Tobian. He is optimistic the therapy will do just that. "I absolutely think this could be the best treatment we have for the next few months."

This passive-antibody therapy has been used since the 1890s to combat diseases as wide-ranging as measles, SARS, Ebola, H1N1 flu, and polio—and holds the promise of keeping the virus at bay until a vaccine can be developed. (Current estimates are that a vaccine for emergency use could be available by early 2021.) During the SARS outbreak in 2002–2003, an 80-person trial of convalescent serum in Hong Kong found that people treated with it within two weeks of showing symptoms had a higher chance of being discharged from hospital than did those who weren't treated.

The beauty of the therapy, says Casadevall, is that it involves the well-established—and safe—method of blood donation. Except in this case, survivors' plasma (or serum), which contains the antibody to COVID-19, is separated from red blood cells and transfused into the three categories of recipients: the critically ill as a last-stop "compassionate care" measure; patients who are slightly or moderately ill to keep them out of ICUs and off scarce ventilators, and front-line medical workers to prevent them from getting sick. Nearly a cup of the serum (200 milliliters, or one unit) would be administered to each recipient, according to Tobian, with each donor providing enough serum for up to four patients. (Each donor, depending on body size, can provide two to four units.)

Casadevall had the vision for this treatment. He also had the wisdom not to micromanage his team of doctors, whom he set free to create their own fast-flowing mini-teams. Together, they united with peers around the world in a marathon of selfless, round-the-clock work toward an urgent common goal—to overwhelm and crush the COVID-19 virus. "Looking forward to another day of working with an incredible set of colleagues," tweeted Casadevall in late March. "Day began at 4 a.m. and will go to near midnight." In this process, doctors, researchers, and regulators from as far away as Israel and Ethiopia banded with Hopkins doctors to create treatment protocols, open labs, win regulatory and institutional approvals, identify donors, compile data, and organize and share vital information. The research effort received a welcome boost in late March with a gift of $3 million from Bloomberg Philanthropies and $1 million in funding from the state of Maryland.

"We usually spend a year preparing for the next flu season," says Andy Pekosz, vice chair of the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. "What we do for flu in a year, we're trying to do in a month for COVID-19. Our window of acting is a small one." The fast-spreading coronavirus has already killed at least 70,000 people around the world, with nearly 1,300,000 total confirmed cases. Numbers that continue to grow.

From the beginning, Casadevall knew he faced more than a medical problem. Plasma therapy's history was unknown to most people, so he needed to draw public attention to his cause. Realizing a medical journal commentary would reach a limited audience, Casadevall shopped around an editorial that urged the use of convalescent serum. The essay, published in the Feb. 27 edition of The Wall Street Journal, told the story of an ingenious Pottstown, Pennsylvania, doctor who in 1934 arrested a measles outbreak at a boys boarding school by using serum therapy. "A remarkable victory against a highly contagious disease," Casadevall wrote.

Casadevall fired off the essay to dozens of colleagues who encouraged him in his plan to also publish a scholarly paper that conveyed sufficient technical information to prove to the medical community he had done his homework. In four days, he and long-time collaborator Liise-anne Pirofski, head of the infectious diseases department at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, wrote what Casadevall calls "maybe the most important paper in my life"—'The Convalescent Sera Option for Containing COVID-19,' which appeared in the Journal of Clinical Investigation on March 13. Written in the cool, precise language of clinical experts, the paper concluded, "We recommend that institutions consider the emergency use of convalescent sera and begin preparations as soon as possible." But its final sentence carried a sharp and decidedly unscholarly sounding warning—"Time is of the essence."

The result? "Everything took off," says Casadevall. "Its publication coincided with the major increase in cases in the United States. The media jumped on it."

Had it not been for a tropical pet bird whose guano infected its owner in 1995, Casadevall's path might never have crossed with that of infectious disease specialist Shmuel Shoham, an associate professor of medicine at the School of Medicine. "That was how we bonded," recalls Shoham, who hammered out the first protocol for the treatment of potential COVID-19 patients.

Back then Casadevall was at Albert Einstein in the Bronx while Shoham was at Boston University, but thanks to a mutual friend, they co-authored a ground-breaking paper in the Annals of Internal Medicine that was picked up by The New York Times. Their research proved the hitherto unknown link between human fungal illness and "cockatoo poo," as Shoham puts it.

Over the years, their careers took them to different cities and in separate directions, but when Casadevall arrived at Hopkins five years ago, they renewed their friendship and became key collaborators again. In mid-February, when Italy reported mounting cases, Shoham began thinking: "If there's a hole in the boat, it doesn't matter if it's on my side or your side, we're all going down. If this is happening in Italy, there is absolutely no reason why this could not happen in Baltimore." Then he saw a tweet from Casadevall: "Plasma is going to be the solution." At first, Shoham pushed back, saying the therapy hadn't worked on influenza patients. But those patients were too ill, Casadevall replied, and in a flurry of back-and-forth tweets, he won over his colleague to his point of view.

With the virus beginning to rage in the U.S., Casadevall convened a 7:30 a.m. conference call on March 4, five days after his WSJ op-ed appeared, with a group from Hopkins' Division of Infectious Diseases. Shoham hopped on the call while driving to work. "I told them we had to do [something]," Casadevall recalls. "This was something that was just not on the radar screen. There was silence, and I said, 'We're going to need a protocol.'"

Shoham volunteered to write it. Although he typically spends two-thirds of his time with patients, by fortunate happenstance he had few patients on his calendar, and that gave him time to dive into COVID-19. By the next day he had pounded out the bare bones of a protocol to prevent infection by administering the plasma to those who had been exposed. "It was sort of a really messy protocol with highlights like a 'This Space Left Intentionally Blank' place holder," Shoham says. He finished a more detailed, but still rudimentary, draft in time for Casadevall's next conference call a few days later.

Casadevall fired off the protocol to a Mayo Clinic colleague, who converted it into one for the treatment of early-to-moderate disease, which Hopkins doctors further refined and revised in collaboration with Mayo doctors. This pattern of rapid, long-distance collaboration would be repeated endlessly among other doctors for other needs in the days to come.

"All of a sudden, centers all over the country were saying, 'Oh, my God, this is something we can do.' So, then we had big conference calls with dozens of centers," says Shoham, who is now the FDA's principal investigator for the prophylaxis study, which makes him responsible for all execution and oversight of clinical research on that protocol.

The team had to know how to collect donor serum and how to transfuse it. So, pathologist Tobian and his colleague Evan Bloch, an associate professor of medicine, came aboard. Today, Tobian and Bloch help lead the transfusion group. "We get emails every single day from other hospitals on how we start collection, how we work on the regulatory aspects," Tobian says. "And we're in touch with transfusion medicine physicians across the nation numerous times a day." The pace has been "crazy," adds Bloch, a specialist in neglected infectious diseases.

In a sign of these high-tech times, Casadevall has never met either man. "I don't even know what Evan Bloch looks like," he says, "and I talk to him all the time. These men are magnificent. They rise to the occasion." In-person meetings happen but are mostly regarded as "a luxury" they can't afford because they would put people at risk, says Shoham.

To analyze the serum, Casadevall called in Pekosz. Until March, Pekosz, a basic researcher, had not thought he would be so directly involved in such an effort. But after Casadevall shared his plans, Pekosz realized some of his work could support the need to measure antibodies in the blood before transfusions were done.

"It became a whirlwind, a tornado we got swept up in, part of a massive effort to treat patients and make a direct impact on the pandemic," says Pekosz. In late March, Casadevall emailed Pekosz to say Vice Provost for Research Denis Wirtz had provided $250,000 in funding to launch a new lab to assess COVID-19 antibody responses in serum earmarked for the hospital's patients.

"Arturo said I needed to set up a lab to do this because this may be a really daunting task in terms of the number of patients we want to treat," Pekosz recalls. "At that point, I really understood, 'Wow, this is going to be a beast unto itself.'"

A big piece of Pekosz's job—besides supervising six new lab employees, a staff that may soon double—entails advising other hospitals on how to proceed. "I can't even remember the number of institutions that have contacted me who want to do the same thing. We're trying to work with them to be as close to each other's test results as possible, so we can have consistency across sites."

After Casadevall's initial burst of enthusiasm and organizational action, he confesses there was a moment when things seemed dark. "You realize the magnitude of what you're trying to do, and, in particular, you realize there could be huge regulatory issues," he says. He reminded himself that projects like this had been done by prior generations and in other countries, and with determination, he says, "I never for a minute doubted we could pull it off."

The FDA's approval process is a two-edged sword, according to Shoham, who says one of the biggest issues is the regulatory environment. Seemingly antiquated FDA requirements have sometimes left doctors shaking their heads. A submission of an IND (the application for an investigational new drug) is not official unless it is physically mailed with numerous copies of paperwork. "We could have sent an email [with PDF attachments]," says Tobian, referring to an IND that Hopkins prepared. "Instead we [were] trying to find who can make all these photocopies and send a FedEx package, and everyone's mostly been told they need to be working from home."

Nonetheless, neither he nor Casadevall believes the old-fashioned delivery system slowed the FDA's decisions or their work. "The FDA has an impossible job," Casadevall says. "I would never criticize them. They are working really hard. Their job is safety, and our job is to get this done."

Lysander, the Spartan admiral who conquered Athens in 405 B.C., is Casadevall's hero. "He did something that was unheard of at the time," Casadevall marvels. "He spared the city, and by sparing the city, he preserved Athens.

"To me, my heroes are always humanists—people who do their job, but there is a humane aspect to how they do it," he says. "The greatest thing about being human is the capacity for empathy, the ability to care for others and be optimistic in the worst of times."

Casadevall's team lavishes praise on his leadership. "He is a force of nature," says Shoham. Brilliant, charismatic, enthusiastic, and generous is how Bloch describes him.

"Arturo pulled off what few people could do," Pekosz adds. "He got multiple institutions across the nation to pull together in this project to create the momentum that led the FDA to say, 'We have to do this, because people are moving forward.' There was such a groundswell of enthusiasm for this approach, the FDA had to pay attention to us."

For most of the team, there's been little rest for weeks. When asked how much sleep he's been getting, Bloch replies, "Last night wasn't bad—about four to five hours. It's just continuous work through weekends, through nights." What drives him is partly the worst-case scenario forecasts he reads which he says are "frightening. … You're thinking about the people in the background—the health, social, and economic impacts. Having insight into what is going on can be a little bit stressful."

"There isn't going to be a day off for many, many months," Casadevall says.

People in medicine often think about delayed gratification, according to Shoham, because they never know whether some bit of knowledge they possess today might be needed tomorrow for an unforeseen reason.

"We're not thinking about the next thing," he says. "This is it. This is the one."

Results from the trials in the two New York City hospitals are expected around the end of April. How widely serum therapy is used after that for the time being remains unclear.

"We want now to get the clinical trials done," Casadevall insists. "Compassionate use is going to be available [in the trials]. Convalescent sera is going to be used in the country, there's no question about that. It's already been deployed in Europe. I think the next task is to learn if, when, and how to use it, and for that, we have to do clinical trials."

The Red Cross is seeking people who are fully recovered from COVID-19 and may be able to donate plasma to help current patients with serious or immediately life-threatening COVID-19 infections, or those judged by a health care provider to be at high risk of progression to severe or life-threatening disease. For more information, visit the website of the American Red Cross.