In recent articles for Goldmoney I have pointed out the dollar’s vulnerability to a final collapse in its purchasing power. This article focuses on the factors that will determine the future for sterling.

Sterling is exceptionally vulnerable to a systemic banking crisis, with European banks being the most highly geared of the GSIBs. The UK Government, in opting to side with America and cut ties with China, has probably thrown away the one significant chance it has of not seeing sterling collapse with the dollar.

A possible salvation might be to hang onto Germany’s coattails if it leaves a sinking euro to form a hard currency bloc of its own, given her substantial gold reserves. But for now, that has to be a long shot.

And lastly, in common with the Fed and ECB, the Bank of England has taken for itself more power in monetary matters than the politicians are truly aware of, being generally clueless about money.

Conclusion: the pound is unlikely to survive a dollar collapse, which for any serious student of money, is becoming a certainty.

Introduction

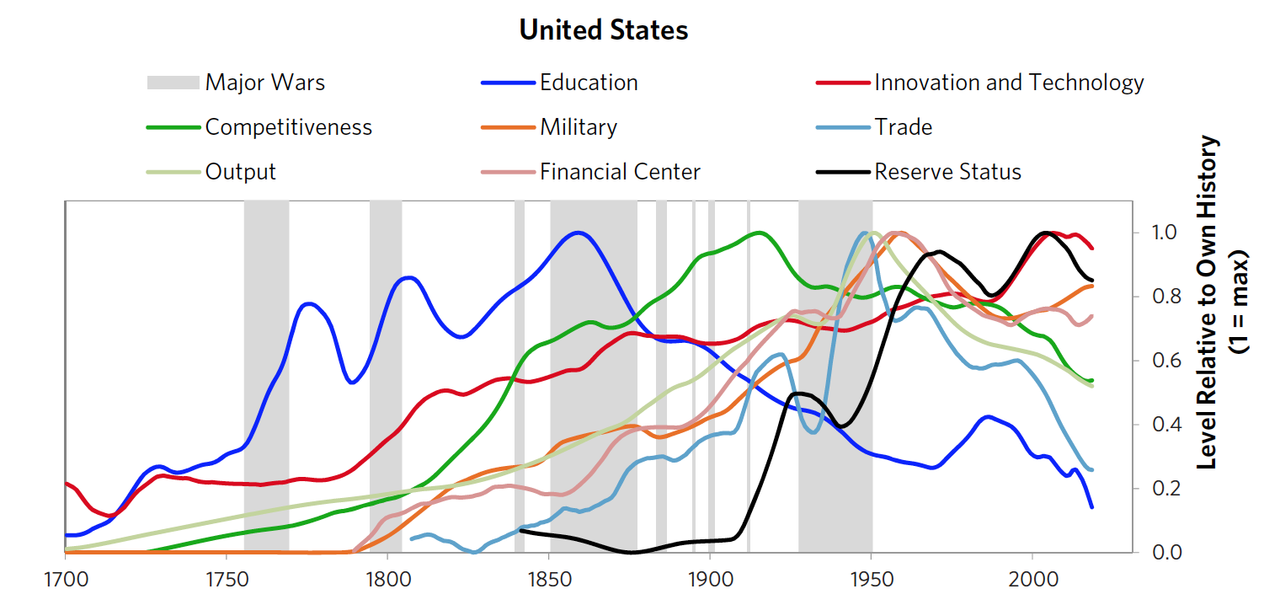

In recent articles I have made a case for the dollar’s demise. Accelerated money-printing is being used to support everything through the coronavirus crisis, which comes on top of a potentially devastating turn in the credit cycle, made worse by the suppression of international trade through tariffs. Only the blind cannot see that with everyone calling for the end of globalisation, it is now actually happening with consequences to follow. Being the grease for global trade the dollar is required by foreigners in fewer quantities and will be sold down by them; they own some $27 trillion in securities, bills and cash, approximately 125% of US GDP in 2019.

It makes the dollar doubly vulnerable to two developing events impacting the domestic front: a global banking crisis and a full-blown depression. The former guarantees an expensive rescue attempt as the Fed has no option but to attempt to underwrite all banking obligations, and the latter will provoke a response of Keynesian inflationism on steroids. Furthermore, such a crisis is bound to lead to dollar long positions being unwound in the foreign exchanges for reasons detailed above, only leaving those required for immediate liquidity needs.

The emerging economic crisis is different from Lehman because it is a collapse of non-financial businesses worldwide undermining the widest extent of banking collateral, while the Lehman Crisis was broadly confined to the unwinding of residential property speculation, predominantly in America. It is therefore a more fundamental liquidation problem, involving considerably greater quantities of debt. Excessive speculation is far easier to wash out of the system than real businesses going bust in large numbers.

A new systemic crisis is imminent because the policy of supporting financial asset values by money-printing will sooner or later fail. Already, it has become impossible for independent observers to reconcile rising stock markets with collapsing businesses, the latter getting irretrievably worse by the day. The commercial banks are stuck in the middle of this crisis, expected to extend credit while their bad debts escalate at a record pace.

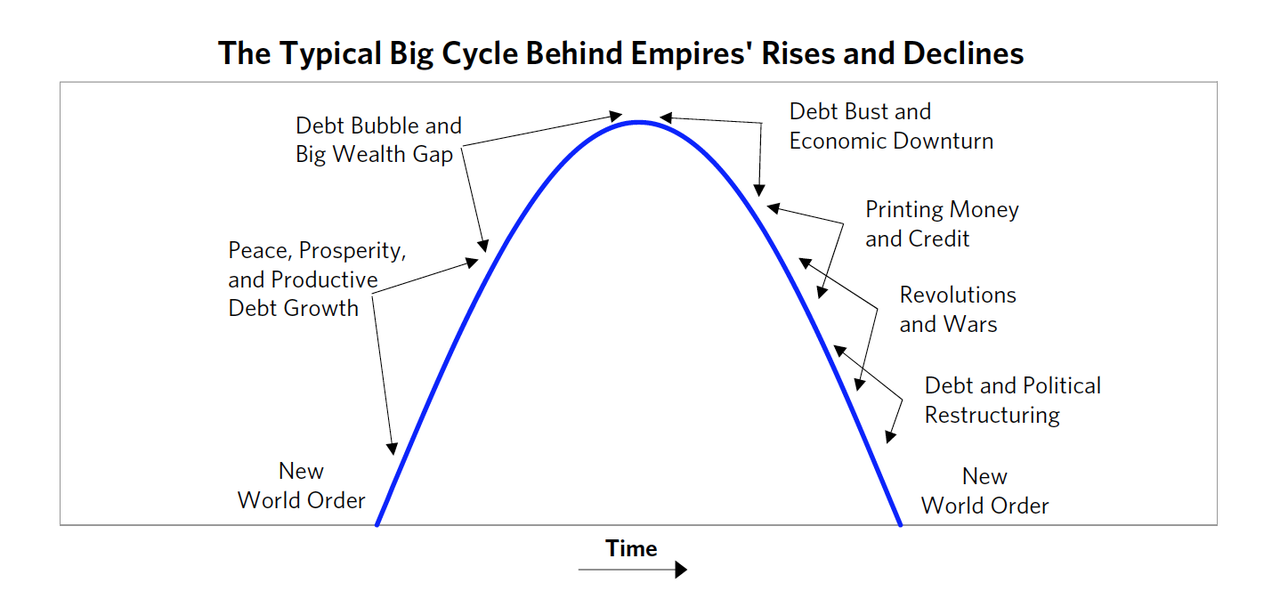

The tensions being created by the authorities’ manipulation of markets in defiance of fundamental factors can only result in a systemic crisis coupled with a crash in financial asset values. By binding their future to an inflation of asset prices, a collapse of fiat currencies will prove impossible to avoid. At least, that is the lesson from John Law when in 1720 his Mississippi scheme collapsed in about six months and his livres currency became entirely worthless.

The reason is not hard to discern. An event such as a banking crisis disrupts investor complacency. A banking crisis is always resolved in the short term by an opening of the money spigot by the lenders of last resort. The Fed can attempt to deal with liquidity, but it cannot stop insolvency. The consequences are that risk assets, starting with equities, are sold as insolvencies rise. And as the asset inflation support scheme of the central banks unwinds, bond yields are reassessed. Defaults become commonplace. Junk becomes junk squared and investment grade descends into junk. Next is the reassessment of government funding requirements, and with the costs required to save the non-financial economy laid bare, even government bond yields escape from the central bank’s manipulative control.

Money and debt are like matter and antimatter: when they come together in a financial black hole they cease to exist. A financial cytokine storm is bound to hit the over-owned US dollar first, being everyone’s international fiat currency. Its purchasing power measured initially against other currencies declines, and then against commodities, energy and the values of life’s essentials. The marker for this outcome is the price of gold, rising strongly and increasingly likely to cause its own crisis for bullion banks, which are currently committed to losses of $38bn on the Comex gold futures contract alone. The only solution for the US is to accept a return to gold. But that is wholly against the DNA of the Fed and US Treasury, and it would hand unacceptable power to the Chinese, who have cornered the physical gold market.

We stand therefore on the threshold of a global fiat money destruction, starting with the US dollar, being expressions of faith in our governments, which are descending into bankruptcy. And when a nation’s population realises that the reason for rising prices is not, as their government is likely to aver, the greed of capitalists but the loss of its unbacked currency’s credibility, it will prove impossible to stabilise it.

While the dollar’s fate increasingly appears to be sealed, the question arises over the fate of other currencies. To greater or lesser degrees, the same underlying factors affect all fiat currencies and the dollar’s demise will require survivors to have introduced at least an element of soundness in their backing. In this article, we focus on how sterling might fare in this outcome, and whether the UK’s monetary authorities can rescue it from the dollar’s fate.

Delusions in Westminster and Whitehall

For an international audience it is worth outlining the difference between these two expressions of the same location: Westminster is associated with Parliament and the politicians while Whitehall is associated with the great offices of state, the bureaucratic civil service whose offices are in the Westminster street of that name. The civil service advises the politicians, so both these arms of government must understand and accept the solution to any crisis. With respect to money issues they have been delegated lock stock and barrel to Threadneedle Street, the location of the Bank of England in the City.

The physical separation between Westminster and the City matters. Not only have monetary affairs been fully delegated to the Bank of England but different cultures have evolved, with Westminster and the Treasury in Whitehall assuming monetary policies are competently managed. But, as they say, power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. There are no meaningful checks and balances on the Bank of England and its monetary policy. And you cannot sack the Governor without creating a monetary crisis.

The BoE is culturally closer to the ECB, the Fed, and the Bank for International Settlements than Westminster. Monetary policy is no longer focussed on the national interest, but a cadre of unelected central bankers, with more power than the political class, have been cooking up their own objectives. A long time ago, Mayer Amschel Rothschild put it succinctly; “Let me issue and control a nation’s money and I care not who writes the laws”.

The situation in Britain echoes that of America in the 1920s. Calvin Coolidge was the last laissez-faire president. But he did not realise what Benjamin Strong was doing at the relatively new Fed. Strong oversaw manipulation of gold in conjunction with Norman Montague at the Bank of England, the rapid expansion of bank credit and the establishment of a discounted bill market, aiming to copy the success of London’s discount houses. The unwinding of this unbacked credit led to the Wall Street crash and the 1930s depression.

Similarly, a British quasi-libertarian government was elected last year, determined to deal with an overly bureaucratic Whitehall, focused on process instead of objectives. Except, and like Coolidge they don’t realise it, the real power lies with today’s Montague Norman in cahoots with today’s Benjamin Strong — Andrew Bailey and Jay Powell.

We must understand the importance of the relationship between the BoE and the politicians. It makes it virtually impossible for the government to control monetary events. Let us assume that key ministers in the government actually understand the importance of returning to a metallic standard and are willing to give up the facility of financing government spending by inflationary means. It will cut no ice with civil service advisors, who are all committed neo-Keynesians. And the BoE will fight strongly to resist, because a gold standard removes the Bank’s power. It makes it extremely unlikely Britain’s free-market government can ween itself away from inflationary financing, even in a monetary collapse. And the current situation is deteriorating rapidly, too rapidly for a disputing combination of Westminster, Whitehall and the BoE between them to regain control over a collapsing currency.

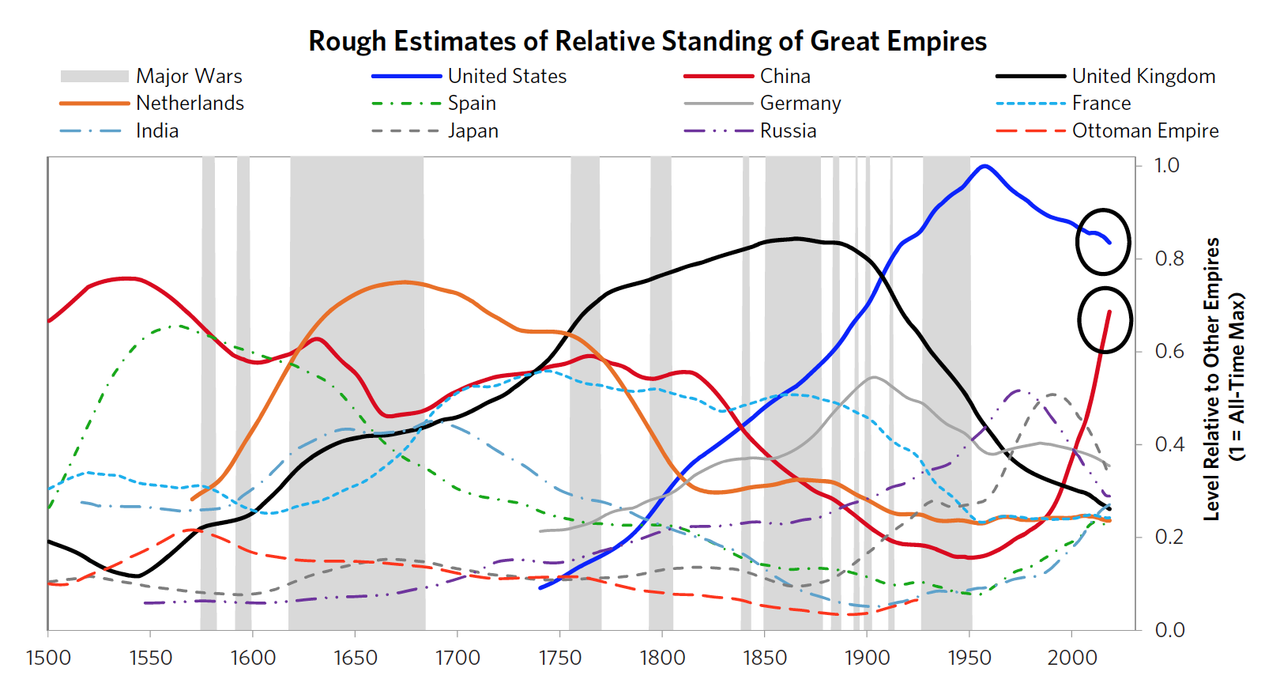

One possible escape route has been closed off in recent weeks, with the British siding with America and therefore her dollar against China and her inherently more promising economic situation. China’s economic policies are far from ideal in the free market sense. China is like all other major nations, relying on inflationary finance to develop her own infrastructure as well as pan-Asian communications and transport facilities. But at least her currency is backed by a high savings rate of some 45%[ii], which as well as reducing the tendency towards price inflation emanating from monetary inflation, provides needed capital for investment in production.

A propensity to save was the defining characteristic of post-war Germany’s mark and Japan’s yen, which is now shared by China’s yuan. And unlike Britain and her allies China’s welfare commitments are minimal, so future government costs are easier to control.

The UK has decided to side with yesterday’s declining power for democratic and cultural reasons as well as the lure of the “special relationship”. It has rejected an alliance with the most dynamic of the major powers, which with Russia as its sidekick is rapidly becoming the world’s superpower, dominating Eurasia and Africa. When the history of our era is written, be in no doubt that we will see that current events, instigated by America, has given China what she really wants: freedom from American hegemony and from her overvalued currency at a crucial time. She can now progress her economy, thanks to its savers, while America continues to destroy hers through maxed-out consumption and monetary inflation.

Furthermore, China has effectively cornered the physical gold market; checkmate for fiat currencies. And not only will America find it intellectually difficult to return to gold, and virtually impossible to return to the necessary balanced budgets, but anything that promotes gold as money plays to China’s strength and America then loses all hope in the financial war waged against China.

Britain’s banks are especially vulnerable

Based on its pre-eminent role in the financing of trade, for some 200 years the City of London has been a major centre in Europe for international finance. Half that time was spent on a gold standard between the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War. Following the latter, New York became increasingly powerful while London declined. After the Second World War and Britain’s descent into socialism and exchange controls, London became less relevant until the Thatcher era, when the removal of exchange controls and the City’s big-bang restructuring made London fully relevant to global finance once again.

The massive expansion of financial business since the mid-eighties reflected the generally non-nationalistic British approach to business. In the European context this is why the nationalists in Frankfurt and Paris by giving preference to national champions could never compete, and the reason why European banks chose London to base their non-domestic lending and investment banking activities.

A general fiat currency collapse will wipe out virtually all London’s existing financial business: over-the-counter derivatives, trade finance, bonds and eurobonds, equities — these will be only some of the casualties. So far as the UK Government is concerned, tax revenue from these activities are over 10% of its total income and their failure will immediately throw up a matching budget deficit — virtually impossible to finance in these conditions. The other side of the coin is what happens to the UK’s banking system in a global systemic collapse, to which the UK is much exposed because of its financing pre-eminence.

According to the Bank of England’s database, total outstanding financial institutions’ sterling and foreign currency assets at 31 May stood at £8.12 trillion ($10.2 trillion), 3.6 times UK GDP. In a banking crisis the government would have no option but to take these assets on board or to alternatively underwrite loan losses in their entirety. Furthermore, without the continuing support of stable financial asset values — which is inconceivable following a systemic crisis of any magnitude — then net liabilities will be uncovered, and losses will accumulate. In other words, if in this inflationary environment stock markets crash and bond yields rise, the government will be exposed to further catastrophic losses.

The Bank of England’s database does not include assets and liabilities of the foreign subsidiaries of financial institutions which are a further substantial sum. Do not expect their automatic inclusion in any rescue package. These losses will have to be addressed in other financial centres and given that offshore centres do not have safety nets for depositors the losses and consequences will be considerable. Nor do they include shadow banking, estimated by the Office for National Statistics in 2018 to be a further £2.2 trillion, though this figure fluctuates wildly.

There is a further complication, and that is the divorce of Chinese activities from the Anglosphere, affecting both HSBC and Standard Chartered, two major British banks with substantial Chinese and Far Eastern businesses. The politics of the situation are at odds with financial reality, and criticism of China’s non-democratic regime risks ending up in a rescue attempt of these banks by the BoE and the Treasury, while rapidly disappearing business leaves the British holding the remaining liabilities.

The context of Brexit

The UK is negotiating trade terms with the EU to apply following the implementation period which expires at the end of this year. The promise of a golden future, which certainly chimes with the Prime Minister, is embodied in free trade. Free ports are proposed. With members of the Commonwealth free trade agreements can be easily negotiated with good will on both sides, and agreements with Japan and South Korea can be simply novated from existing EU agreements. But the prospect of a fast-tracked agreement with the US may be receding, with President Trump increasingly distracted by domestic concerns in this his election year.

The lack of a trade agreement with the EU is less of a threat to the UK than commonly argued, the greater losers by far being the EU. However, the UK is still financially obligated for EU economic programmes. According to Brexit Central, under the current Multiannual Financial Framework Britain could be on the hook for financial claims up to €478bn, though this is disputed. More important is the UK banking system’s counterparty risk in the event of an EU banking crisis.

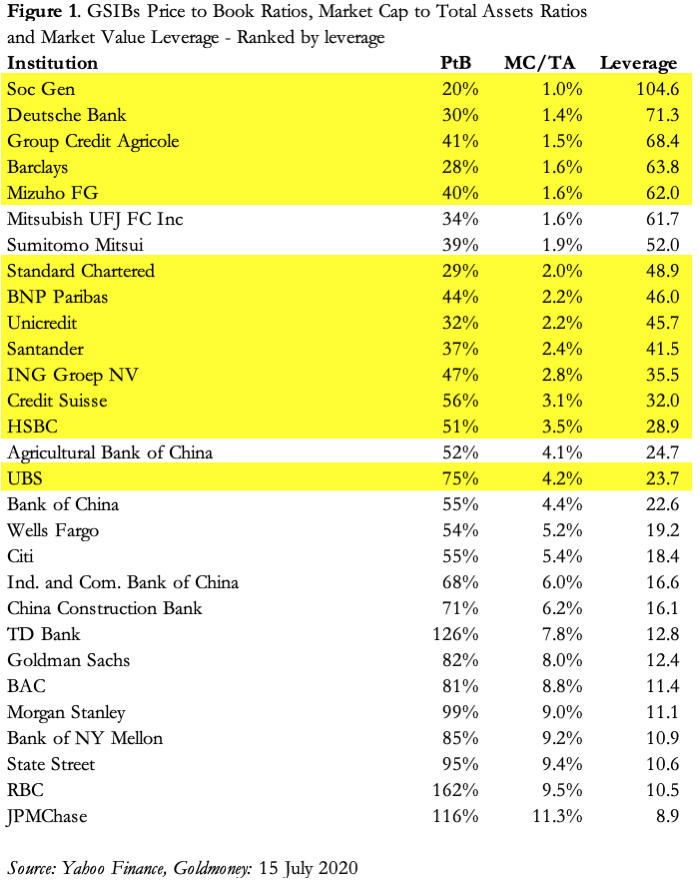

In Figure 1, global systemically important banks (GSIBs) in Europe and the UK are highlighted in yellow. The most highly geared banks are in the Eurozone, when total balance sheet assets are compared with the market capitalisation of banks’ equity. Of the fifteen most highly geared, only three banks are not European, and all three UK GSIBs are in this category.

The most extreme of the GSIBs is Société Generale, currently with assets over 100 times its market capitalisation. The difficulties of the major German private banks, Deutsche and Commerzbank (not a GSIB) have been widely publicised, as have those of Italian, Spanish and Greek banks. When a systemic crisis hits global markets, there’s a good chance it will start in the European time zone, for which London remains the financial centre.

It’s not just about COVID-19

So far, planned spending in connection with the coronavirus amounts to an estimated £190bn — about 7% of M1 money. The hope is that once the crisis passes, the economy will revert to normal – the so-called V-shaped recovery. As this prospect recedes, businessmen will review their forecasts, and the majority will either close or downsize their operations.

The purpose of the furlough scheme was to bridge a V-shaped recovery and prevent massive unemployment, but that ends in October, having kept over nine million people out of the unemployment statistics. Unless there is some sort of miracle, many of these will be unemployed when, or even before the furlough scheme ends.

The extra spending on the furlough and other schemes has been covered by the Bank of England’s £200bn quantitative easing programme on a one-off basis. Doubtless, as the situation evolves there will have to be further funding by this route, otherwise funding costs will rise sharply.

Having gone nap on a V-shaped recovery it is not clear how the government plans its exit. Governments almost always make the mistake of thinking there is an economic normal to which a previous situation can return. This is the underlying assumption behind statistical measuring and economic modelling. Instead, economies are dynamic except in a totalitarian regime where everything is rationed by a central committee. But we know that doesn’t work, as demonstrated when the Berlin Wall fell.

There is therefore no “normal” to which to return. Subsidising existing businesses and furloughing staff is an encumbrance to necessary changes in production in order to satisfy consumers, who will have changed their needs and wants. For example, if the coronavirus is conquered and all social interaction returns, it is reasonable to assume that consumers won’t be in the market in large numbers for luxury SUVs to the same extent, yet manufacturers have been investing their production heavily in this direction for the last twenty years. Before the lockdown, retailers deemed it necessary to have branches in every city and every shopping mall, in order to secure and maintain market share. Their priorities have now changed from these strategic objectives to conserving capital.

To be fair to Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor, he appears to understand this point and has made available interest-free finance to small and medium size businesses. Partly, that will be used by businesses to stabilise their finances, but it does give the opportunity for entrepreneurs to fund new ventures. But even then, subsidised capital is usually taken up solely for the opportunity rather than to fund a properly considered venture, leading to malinvestments exposed at the turn of the next credit cycle.

But there is one thing clear: even with a government dominated by ministers more libertarian than any since the Thatcher era and therefore sympathetic to free market solutions, there is no exit plan that fully recognises the role of free markets. Government spending as a proportion of GDP has increased, will increase further and is unlikely to decline. Nor is there any recognition of the global bank credit cycle and its consequences. Forgotten is the downturn in global trade, which for an entrepôt nation is vitally important. For different reasons, the developing crisis for the dollar is also developing for sterling.

Can sterling avoid the dollar’s fate?

The economic solution to preserve the currency can be easily described. The problem is whether those in charge understand it after decades of Keynesian intervention and inflationism. Not only must Keynes’s theories be jettisoned, but the whole macroeconomic paradigm as well. And there must be an unequivocal acceptance that the role of the state must be rolled back to only the defence of the nation, the provision of law and order and to maintain clear, simple contract law. Taxes must be substantially reduced but balanced budgets maintained as well. Socialism must be ditched, and the people be permitted to build and maintain their own wealth.

That it can be achieved without going onto a gold standard was shown in Germany following the collapse of the paper mark in 1923, and again in Germany in 1948 when Ludwig Erhard piloted the nation from post-war destruction to becoming the wealthiest European nation by the time of its reunification. His recipe was simple: remove control of the economy from the Allied military administrations and hand it back to the people.

Germany had monetary stability without gold, but under the Bretton Woods agreement the dollar was a sheet anchor, directly (or indirectly in the case of Britain and France’s colonies). Germany used this breathing space to build her own gold reserves. Low government spending, a growing savings culture and growing exports allowed the foreign exchanges to set a rate for the mark confidently, giving it added credibility for the German people who welcomed the opportunity to save appreciating marks. But today, no such exchange stability will exist when the dollar collapses, except for those nations which take appropriate monetary action.

Therefore, a precondition for stabilising the currency without gold is that there are other stable currencies. After this crisis wipes out purely fiat currencies it will therefore require a return to gold backing for the few survivors. Britain foolishly sold most of her gold when Gordon Brown was Chancellor of the Exchequer and has only 310 tonnes left. As a rule of thumb that works out as £8,600 of M-zero money supply to one ounce of gold, comparing badly with Britain’s European neighbours.

It is worth noting that Germany, France and Italy do have significant gold reserves. A sub-optimal solution for them would be to transfer these reserves to the ECB and the ECB to use them to stabilise the euro. Better solutions can be had. The ECB has shown with its monetary policies to be entirely reliant on unsound money, with which it is destroying the eurozone’s banking system. Its management is incapable of being re-educated. As an institution it should be dismantled before it does any more harm.

Meanwhile, the Bundesbank has been forced into silence on the matter, retaining at its core a few influential sound money men, despairing of a solution. But for them to take over control of ECB policy would be politically divisive, making it virtually impossible to deliver monetary stability.

The practical and political choice would be to withdraw. German politics, informed by two currency collapses in the last hundred years, strongly suggests Germany would choose to go it alone with its own gold-backed currency. Far better for Germany to abandon the money side of the European project. This would be a major development, leading to the destruction of the euro. But with the collapse of the dollar and the current ECB management in charge, this would be seen as an increasingly likely outcome for the euro anyway.

If a new German mark had gold backing, the Netherlands would probably join to form the nucleus of a gold-backed bloc. France and Italy have the gold reserves but lack budgetary control. Whichever way it pans out sound money could emerge in Europe, in which case the right economic policies in the UK might have a chance of stabilising the pound, because there would be a basis of comparative valuation for it on the foreign exchanges and a complete monetary collapse might be avoided. But compared with having and deploying credible gold reserves it would be rather like playing league-level football with your shoelaces tied together.

Conclusion

Despite having the most libertarian government for the last forty years, there is little sign any senior ministers really understand monetary affairs. Furthermore, by giving over responsibility for money to the Bank of England, there is a feeling in Westminster and Whitehall that there is no need to worry about how the Bank achieves agreed targets on unemployment and price inflation. The result is the Bank is now arguably more powerful than the executive, planning monetary policies with other central banks instead of for the direct benefit of the British Isles.

Britain faces a difficult time in the next few months. A global banking crisis can be taken as read, requiring the government and the BoE to backstop all banking obligations. The destructive monetary policies of the ECB, with which the BoE has been complicit, should drive Germany to re-establish the mark, hopefully backing it with gold to form the nucleus of a new European sound money regime, but there is no guarantee of this outcome.

Furthermore, by submitting to America’s anti-China policy, Britain has done away with the one possible economic and monetary lifeline at its disposal. Clearly, no one in government thinks this really matters, showing a lack of strategic vision.

It will be a brave Britton who relies on the survival of his currency through these extraordinary times.