Sunday, September 13, 2020

Saturday, September 12, 2020

Friday, September 4, 2020

Reporter Who Brought Down Wirecard Details Sprawling 'Corporate Espionage' Operation

As Germany finally officially drops its investigation into the Financial Times over the paper's pursuit of Wirecard, a campaign for which it was eventually vindicated, the Financial Times investigative reporter who broke the story is opening up about the experience of trying to take down a veritable corporate titan, and how both Wirecard and elements within the German government tried to silence him and the FT.

The above-mentioned investigation is perhaps the most egregious example of this conduct. While Wirecard was carrying on a massive fraud in southeast Asia, conjuring billions of dollars in profits via an elaborate shell game, its now-former CEO Markus Braun was working to strike a deal with Deutsche Bank that could have served as a neat coverup.

In a statement released yesterday, Munich prosecutors said the information reported by McCrum and a colleague was "basically correct". BaFin, the German financial watchdog that recommended the investigation, said it had no objections to dropping the investigation into the FT, though BaFin says it's still looking into possible manipulation by short-sellers.

In a story that's, in some ways, reminiscent of a certain actress's story about how Harvey Weinstein cowed her into keeping quiet about a sexual assault perpetrated by him, McCrum recounts how German regulators, and later prosecutors, accused him of an illegal conspiracy. Wall Street analysts accused him of unscrupulously working with short sellers. He was stalked by shadowy figures. His emails were hacked, and swarms of twitter bots slandered him online and taunted him about "going to jail". At times, white-shoe law firms demanded that his employer, the FT, fire him immediately.

At times, McCrum wrote, it felt like "the world had gone mad". But he persevered, mostly because he had a high degree of confidence in his reporting, and because he and the FT's editors and lawyers had braced for a long, difficult road from the beginning.

I’d investigated Wirecard since 2014, following a tip that something was awry with the accounts. Together with the FT’s investigations team editor Paul Murphy and in-house libel lawyer Nigel Hanson, we had learnt what to expect from scrutinising the company: furious online abuse, hacking, electronic eavesdropping, physical surveillance and some of London’s most expensive lawyers.

After publishing their first major report on leaked allegations of rampant fraud at the company, Jan Marsalek, the WIrecard COO who is currently a fugitive from justice, started finding ways to push back against McCrum and his reporting by identifying the reporter's sources and trying to influence them.

It was amid this tumult that Paul Murphy, who at the time edited FT Alphaville, took an odd phone call. A stock market speculator and gossip who Murphy spoke to in private on a pretty regular basis — call him Bill — wanted to make an introduction. Was Murphy really sure about “the stuff on Wirecard” on FT Alphaville, he asked? Bill said he was in touch with someone who vehemently disagreed. His name was Jan Marsalek.

Marsalek, then just 36 years old, was the chief operating officer of Wirecard and the mastermind of its dirty-tricks operation. A suave dealmaker who lived half his life in private jets and luxury hotels, he thrived where the worlds of business, crime, politics and spycraft intersect, a solid gold credit card tucked in the pocket of his designer suit. We now know that he had a range of secret-service contacts in Russia and Austria, as well as deploying at least a dozen private investigators in multiple countries. Documents seen by the FT indicate Wirecard had a broad toolkit at its disposal, ranging from a cast of social-media sock-puppets spouting propaganda to physical surveillance to sophisticated eavesdropping kit used to mirror iPhones.

However he’d done it, Marsalek had identified one of Murphy’s regular sources — and hoped to use him to influence the FT’s reporting.

Pretty soon, strangers were approaching FT reporters in public, and offering them thousands of dollars to remove critical posts, while also trying to cynically plant positive news that might help bolster the stock.

Within days, Marsalek tried a different route into the FT. Bryce Elder, an equities specialist on the paper, returned from a Mayfair lunch and sat down next to Murphy in the newsroom. "A strange thing just happened to me," he said. "I was offered money to quietly remove the Wirecard posts from Alphaville. Of course, I told him where to go but he said there’s a takeover bid coming for Wirecard."

After that incident, Wirecard's tactics became much more sophisticated, and Marsalek's behavior even more brazen. Once, Marsalek personally confirmed a phony rumor about an upcoming deal between Wirecard and a major rival based in France.

Dan McCrum

The FT didn't take the bait, but McCrum and his editors were rattled nonetheless.

In April 2016, rumours started to circulate among London stock market traders that the FT was about to report that Wirecard was in takeover talks, and that the newspaper would issue a correction and an apology for its past coverage. Elder, who keeps his ear close to this rumour mill, was quickly told the terms of the supposed bid: Wirecard would merge with its French rival Ingenico. He also received a name and number to contact for verification of the deal: Jan Marsalek. Marsalek, who was in Moscow at the time, answered his call and confirmed the takeover: Wirecard had supposedly reached heads of agreement with Ingenico in a transaction designed to create a European payment-processing powerhouse. The price would be €60 per share, 70 per cent above the prevailing market price — a bid premium that would stun investors. But as Marsalek spoke, calls were simultaneously going into Ingenico executives from our Paris office. The French were adamant: there were no talks, there was no deal, the story was fictitious. Ingenico even produced an on-the-record statement.

At the FT we were dumbfounded. A senior executive at a large publicly listed European company had brazenly tried to spoof our journalists into running a completely fabricated, highly price-sensitive story. This was simply outside of our experience and, while it cemented our conviction that something was up, it was also deeply intimidating. What other tactics would the company try, I wondered.

Wirecard's next salvo would strike even closer to home. It included a leaked cache of documents including hacked correspondence from hedge funds betting against Wirecard, as well as copies of McCrum's emails and doctored chat logs to make it look like the FT was in cahoots with investors, all part of a nefarious conspiracy to pick on an innocent German payments-processing giant.

In December I found out, when screenshots of emails between me and a corporate investigator were posted online for all to see. More worryingly, they appeared along with a collection of doctored chat-message transcripts, presented as evidence that I was synchronising the publication of Wirecard-related content with various hedge funds. Wirecard’s associates, helped by an Indian hacker team, had invented their own “whistleblower” who published this cache of supposed evidence as a file called Zatarra Leaks. It included hacked correspondence between hedge funds, clandestine surveillance photos of investors at their homes — and my emails. This was accompanied by a rabid conspiracy about London-based traders and corrupt journalists ganging up on an innocent German technology company. Panicked, I replaced all my personal electronics and spent days setting elaborate passwords on every device. On the advice of Sam Jones, who covered the security services for the FT, I attached a timer to my WiFi router to turn it off at night and reduce the opportunity for attack.

When the paper pressed on undeterred, Marsalek arranged an interview with McCrum and his editor through a back-channel. The rumor was that he was planning to offer them $10 million to drop the investigation.

In early 2018, Murphy was lunching with one of his regular “bid-gossip” contacts at Signor Sassi, a splashy Italian restaurant near Harrods, when Wirecard came up in conversation. “You know they will pay you good money to stop writing about them,” the market contact stated. Murphy smiled, dismissing the idea. “No, I’m serious, they will pay you proper money,” he insisted. “They will pay you $10m. Go and talk to Bill. He’ll help you."

Our immediate assumption was that this was a trap — a sting to demonstrate an FT journalist could be bribed. If there was going to be a lunch with Marsalek, we had to monitor it covertly. The meal in question was arranged with surprising speed — for February 16 2018 — and, ultimately, took place at a steak restaurant at 45 Park Lane, where the prices naturally limit the number of people dining on any given day. Along with Marsalek came Bill and his son, plus a mysterious character called Sina Taleb, who couldn’t quite explain why he was there. Nearby, presenting themselves as three “ladies who lunch”, were Cynthia O’Murchu and Sarah O’Connor from the FT investigations team, as well as Camilla Hodgson, then a trainee FT reporter. They discreetly videoed proceedings with a high-tech handbag, while Murphy was covertly mic’d up

It was for naught: Marsalek didn’t offer Murphy $10m. It may be that a last-minute venue switch exposed our amateur surveillance, or he wanted Murphy to make the incriminating “ask”. Marsalek did voice his belief, based on what he claimed was his direct experience, that journalists could be easily bought. And he repeatedly pressed his line that, knowingly or otherwise, I was working with short-sellers to damage Wirecard stock.

During that lunch, McCrum said, Marsalek openly admitted that he was running a spy operation into the FT.

What Marsalek also admitted to, albeit indirectly, was running a spying operation against us. (“Maybe friends of mine did it,” he said.) And he explained, almost candidly, why this was needed: a misinformed or malicious FT story represented an “existential threat” to Wirecard, which, like any financial institution, had to retain the trust of those it did business with. “If we lose our correspondent banking relationships, the business would go down almost overnight,” he said.

In October 2018, McCrum and one of his colleagues finally met in person with a whistleblower in Singapore who leaked a cache of documents to the FT that offered clear proof of manufactured cash flows via a process known as "round tripping". When the FT moved to publish its next report, editors were surprised when, just hours before it went live, contacts started asking questions about an impending story. Floored by the possibility that they might have a leak, despite all the precautions taken, McCrum and his editor swiftly realized that the leak had come from Wirecard. It was clear Marsalek was now trying to frame the FT for working with speculators.

At Sweetings, he’d taken a call from a market trader, who said he’d heard there was a Wirecard article coming at 1pm and wondered what we were reporting. We sat and rolled through the names of those who knew we were planning to publish that day: the two of us, Nigel the lawyer, Lionel the editor. That was it. The copy wasn’t even in our content-management system yet. There was no leak from the FT. The penny dropped: any leak must have come from Wirecard. Alerted by our questions, it had spread the news through the London market and once again was about to accuse us of collaborating with market speculators. The evidence was in the reference by Murphy’s caller to publishing at 1pm. We were never going to publish at that time; 1pm was simply the deadline given for comment. Right on cue, a letter arrived from Schillings: “Our client has been informed of large and unusual short positions being taken out this morning against it, in anticipation of the publication of damaging information or allegations about it which would negatively impact its share price, as previous Financial Times articles have done . . . The repeated pattern of collusion with market players and, particularly, the timing of the short positions being taken out coinciding with Mr McCrum’s approaches, is particularly suspicious . . . ”

Even more amazing: Almost the entirety of the German business establishment, including BaFin, the German financial regulator, sided with Wirecard over the FT. Soon Munich prosecutors had opened a criminal investigation into McCrum. False claims that McCrum and a colleague had tried to bribe the company's southeast asian partners also spread. BaFin followed up the investigation with something even more extraordinary: a ban on short-selling in Wirecard shares. This, combined with news that Japan's SoftBank - back in the news late this week - had just backed Wirecard to the tune of more than $1 billion.

Wirecard shares came roaring back. And yet, despite the company's seeming invulnerability, Wirecard's efforts to target critics and shortsellers only intensified. Soon, the company hired a former head of Libyan intelligence, who in turn worked with an old contact from MI5 to build a team of nearly 30 operatives to surveil not just McCrum, but a whole gaggle of reporters and investors bound by the common thread that they were all Wirecard skeptics.

The list of targets included Hedge Fund legend Crispin Odey.

Overseeing the surveillance effort was a maverick Libyan, Rami El Obeidi. He was briefly the head of foreign intelligence in the transitional government installed after the country’s leader Colonel Gaddafi was killed in 2011. He liked to be addressed as “The Doctor” and always stayed at the Dorchester when in London, meeting there with officials from the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority to press a case that I was crookedly conspiring with short-sellers to bring Wirecard down.

It was “Dr Rami” who brought in an ex-special forces guy from Manchester called Greg Raynor to work the Wirecard case. He, in turn, reached out to an ex-MI5 counter-terrorism operative, Hayley Elvins, and together they assembled a collection of 28 private investigators to follow me, my colleagues and a baffling array of investors and hedge fund bosses, including Crispin Odey.

It was pretty clear by now that the FT had become a huge moneymaking machine for these black operations pressing back against our reporting. Arcanum Global, owned by Ron Wahid and advised by a string of former senior military, policing and intelligence leaders, had a £3.2m contract with Wirecard. Elsewhere Charlie Palmer, partner in the public relations arm of FTI Consulting, failed to get the Mail on Sunday to reprint nonsense written by newspapers in the Philippines.

In October 2019, McCrum and the FT finally published the story that sealed Wirecard's fake. After spending months trying to track down Wirecard's Southeast Asian "partners" - and running into dead end after dead end - the paper published a story claiming most of Wirecard's revenues from the region, ostensibly its most profitable operation, were fraudulent.

It only took another 8 months of dithering from the German authorities before Wirecard finally collapsed in the face of an auditor report confirming $2.1 billion was missing from Wirecard's balance sheet.

Now, Marsalek is an international fugitive, and McCrum has clinched the biggest corporate takedown by a crusading journalist since the fall of Theranos.

One Day After Zero Hedge, FT "Unmasks" SoftBank As Call-Buying "Nasdaq Whale"

Yesterday, as the gamma meltup insanity of the past month finally rolled over and tech names tumbled, we said "the real questions emerge and first and foremost is who was it that led this furious gamma charge higher, taking on virtually every dealer?"

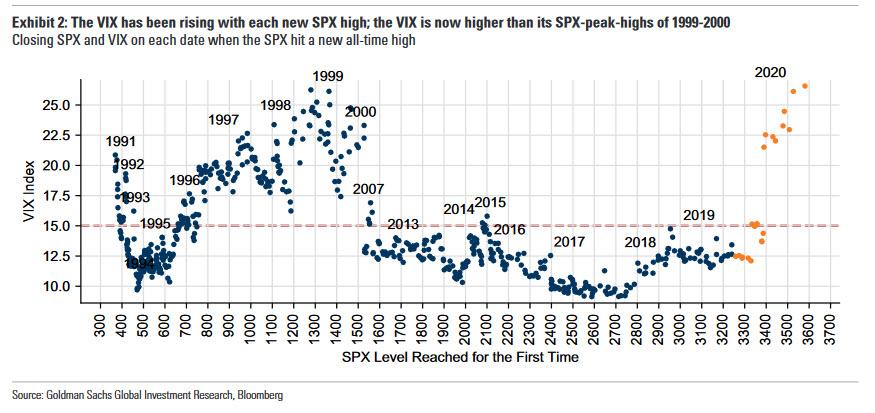

As a reminder, this came following several weeks of bizarre market moves duly discussed here, which we said could be described as an unprecedented "epic battle" in gamma "between one or more funds who were aggressively loading up on gamma and bidding up calls to the point that VIX was surging even as stocks hit 9 consecutive all time highs, while dealers were stuck "short gamma" and in their attempts to delta-hedge the ever higher highs, would buy stocks thereby creating a feedback loop where the higher the market rose, the more buying ensued."

Yesterday, we first identified the solitary party that was responsible for the unprecedented call-buying insanity as Japan's bizarro VC/media conglomerate SoftBank, and elaborated:

It is hardly unreasonable to imagine SoftBank, the "brains" behind such catastrophic investments as WeWork,

WireFraudWireCard, and countless other failed "unicorns" would desperately try to Volkswagen not just a handful of tech names, but the entire market in the process. After all, Masa Son is desperate to deflect attention from the fact that as we put it last October, "SoftBank is the Bubble Era's "Short Of The Century." And if there is one thing that can salvage the Japanese VC titan's reputation it is a second tech bubble which blows out the valuation of his countless (otherwise worthless) investments which form the backbone of SoftBank's "AI Revolution" whatever that means.

Today, one day after our original report, the Financial Times catches up and confirms that SoftBank has been "unmasked as the 'Nasdaq Whale' that stoked the tech rally", writing that Masa Son's investing vehicle "has bought billions of dollars’ worth of US equity derivatives in a move that stoked the fevered rally in big tech stocks before a sharp pullback on Thursday, according to people familiar with the matter" (oddly enough, the FT forgot to note that "this was first reported by Zero Hedge" but whatever.)

While traditionally SoftBank for investing in either unicorns or megafrauds such as WireCard, the FT repeats what we first said, namely that SoftBank has "also made a splash in trading derivatives linked to some of those new investments, which has shocked market veterans." It goes on to quote a derivatives-focused US hedge fund manager "These are some of the biggest trades I’ve seen in 20 years of doing this. The flow is huge."

How huge? Huge enough to send the implied vol of calls of the world's biggest company, Apple, soaring at the same time as its stock price hit record highs.

It's also why the S&P kept rising alongside the VIX, which hit a record high at a time when the S&P was also at an all time high, as we first pointed out on Wednesday, warning that the last time this happened was when the dot com bubble burst.

How much did SoftBank buy? According to the WSJ, which also moments ago confirmed our original reporting, SoftBank...

... spent roughly $4 billion buying call options tied to the underlying shares it bought, as well as on other names

... which due to the embedded leverage in options, is the equivalent of buying tens if not hundreds of billions of underlying stocks, thus sparking the massive upward move in the handful of tech stocks which then spilled over everywhere.

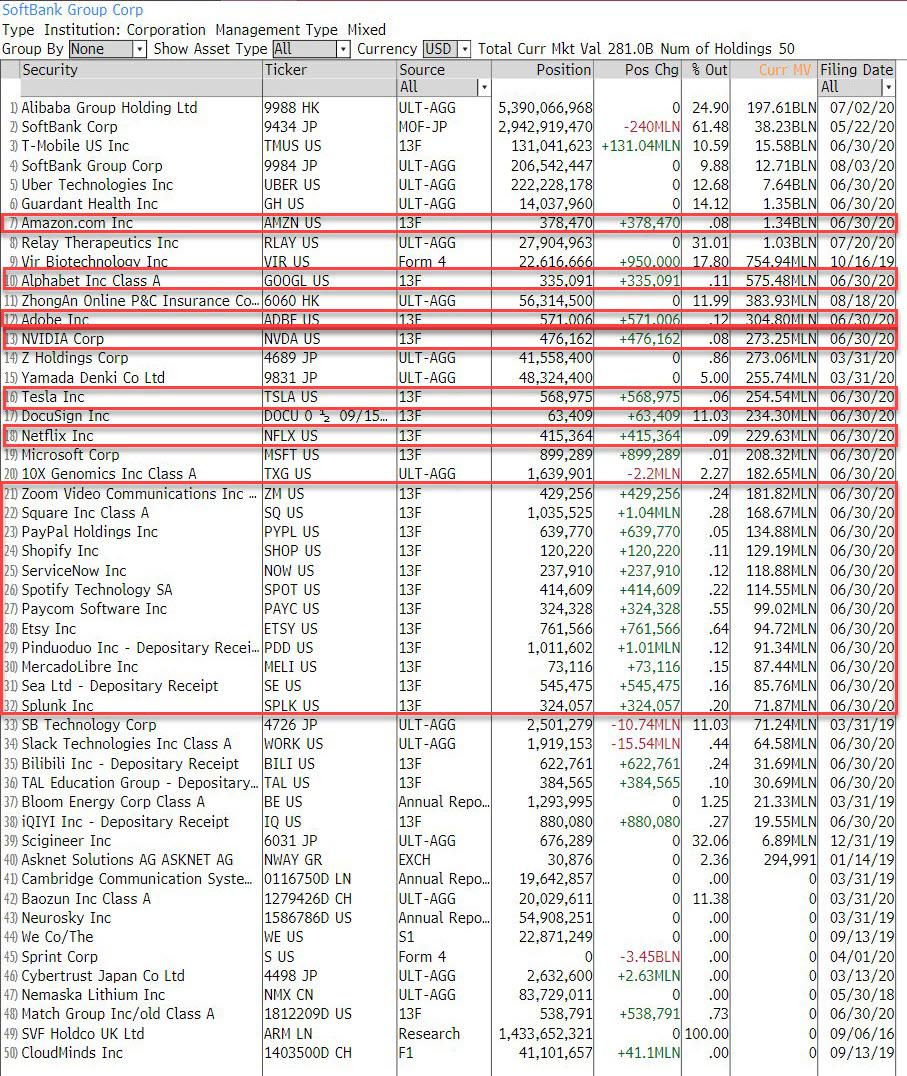

And speaking of underlying stocks, in Q2 SoftBank just so happened bought brand new stakes in all the super high beta names including Amazon, Google, NVidia, Tesla, Netflix, Zoom and so on.

SoftBank's trade was simple: buy billions in underlying ultra-high beta stocks, then also buy billions in call options to take advantage of illiquid markets and gamma, and sure enough all the "SoftBank stocks" exploded to all time highs, and in the process dragged the entire market higher.

Going back to the FT's confirmation of our original report, it quotes another anonumous "person familiar with SoftBank’s trades" who said it was “gobbling up” options on a scale that was even making some people within the organisation nervous.

"People are caught with their pants down, massively short. This can continue. The whale is still hungry."

Or not, because if SoftBank "forgot" to take profits and has been piling on gamma, it is now entirely at the dealers' mercy as we first explained yesterday, which incidentally explains today's continued plunge in tech names as traders brace for the unwind of all that gamma.

Of course, that's the last thing SoftBank - which already is hurting from the dismal performance of so many of its recent investments - wants, and is why a banker "familiar with the latest options trading activity" told the FT that Thursday’s market pullback would have been painful for SoftBank (well, duh), and "he expected the buying to resume" unless of course the dealers double down and sell all those same calls that exploded in recent days. The FT then added, perhaps for the benefit of its Robinhood readers that "a larger and longer-lasting stock-market decline would be more damaging for this strategy, and would probably involve rapid declines."

While there was nothing actually new in the FT report beside merely confirming what our readers already knew, all we can say is that we sincerely hope that Masa Son publishes all his material derivative holdings so the public can take the other side and finally crush this grotesque company which last October we said was the "Bubble Era's "Short Of The Century"."

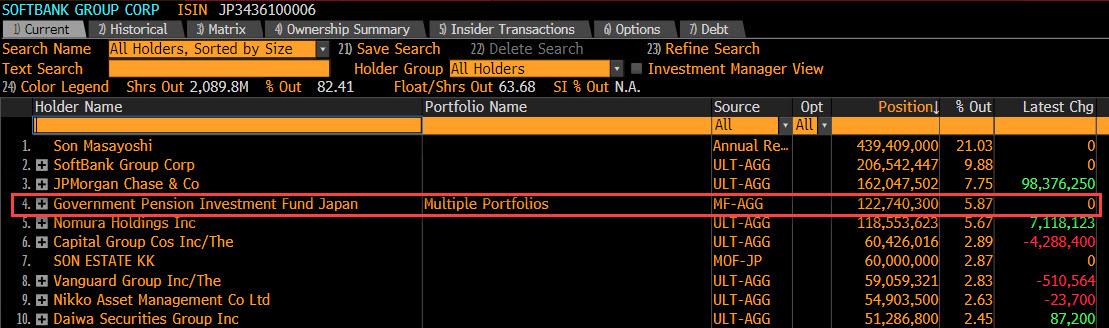

Meanwhile, for those wondering just how far from the Minsky Moment we are, it appears that Japanese pensioners - who are the 4th largest holder of SoftBank - are now indirectly buying deep OTM Apple and Tesla calls:

One final point: while there is an amusing feud brewing between the FT and the WSJ about who broke the SoftBank story (spoiler alert: neither)...

... the real question is which media publication will refuse to touch on the next part of this story, and where the rabbit hole really goes: namely the frontrunning of call options by certain HFTs who clearly magnified the gamma effect sparked artificially by SoftBank.

Wednesday, September 2, 2020

Angry Robinhood Traders Unleash Tsunami Of Complaints

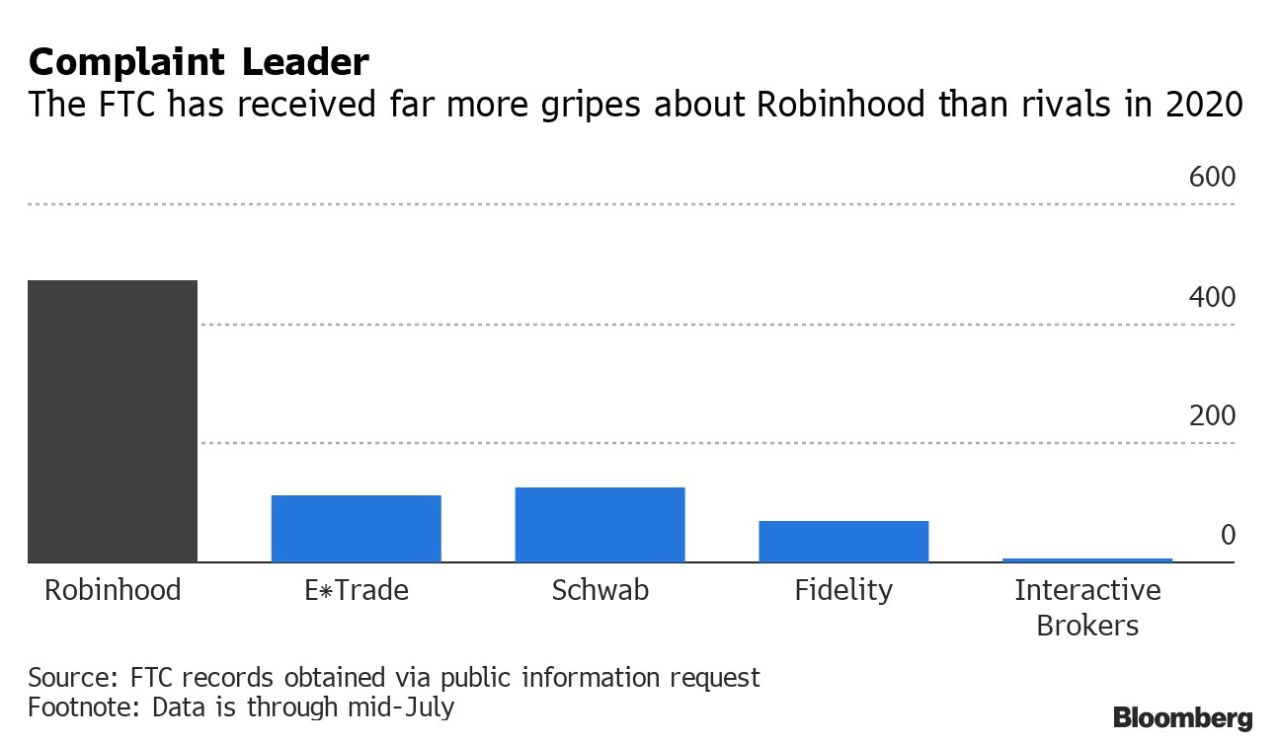

Robinhood's quick rise to the top of the brokerage world hasn't come without speedbumps. To wit, US consumer protection agencies are being flooded with complaints about the app. In fact, four times as many complaints are being filed about Robinhood than other traditional brokerages like Schwab and Fidelity, according to Bloomberg; in 2020 alone more than 400 complaints have been lodged against the "free" daytrading app.

The complaints have featured "novice investors in over their heads, struggling to understand why they’ve lost money on stock options or had shares liquidated to pay off margin loans."

Complaints were also filed when Robinhood's app went down for a full day back in March during the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Users complained about losing money and not being able to sell holdings (in retrospect, they should be praising the company for preventing them from dumping just before the Fed nationalized the market and sent the S&P 61% higher from the March lows). They complained about not being able to make money because the app was down. A legitimate grievance: no phone number, or direct contact at Robinhood have been listed, probably because the company still can't afford a client-facing support team.

One complaint unearthed by Bloomberg in a FOIA request stated: “It just says to submit an email. This company’s negligence cost me $6,000.”

Another complaint, from a user who estimated they lost $20,000, said: “I can’t make trades, can’t take my own money and can’t leave their service.”

The complaints are par for the course for a company that has focused solely on growth over the last few years. Robinhood has signed up more than 3 million clients in the first four months of 2020 alone and has become the go-to app for those in quarantine, receiving unemployment and looking for something to do all day.

Regulators have received so many complaints, they have joked that they feel like they have become Robinhood's customer service department (it's funny cause it's true). Both the SEC and FINRA are currently investigating how the company handled its app's outage in March. Their findings and any enforcement action is being watched closely, as it may interfere with plans for an IPO that is widely expected from Robinhood, which is now valued at $11.2 billion after its latest round of funding.

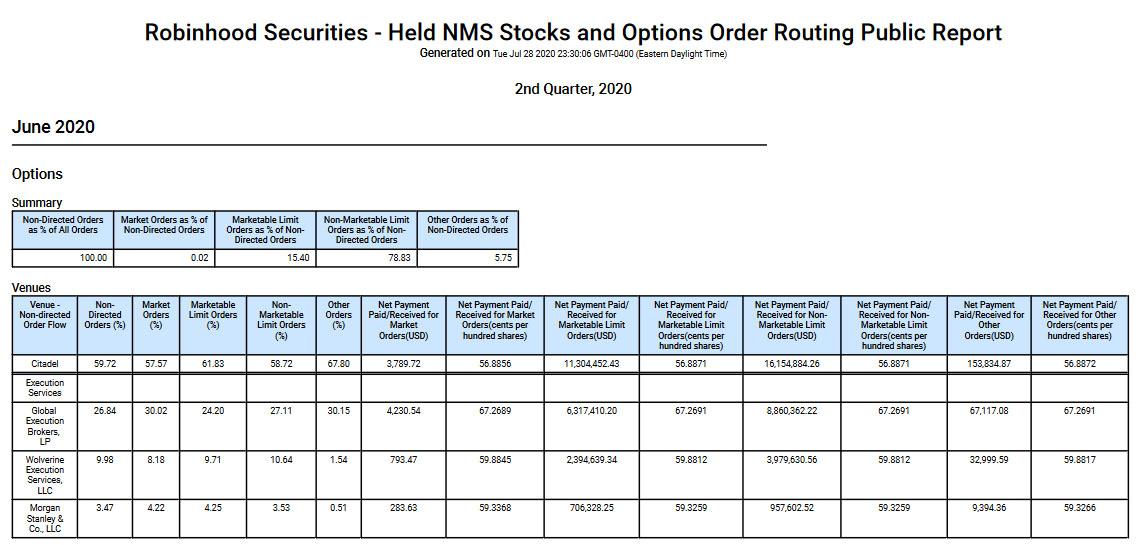

Robinhood has responded by saying it has doubled its customer service representatives this year and is "hiring hundreds more". They have also said that after the March outage, they have strengthened their platform and improved reliability. The company is able to offer free commissions because it sells its order flow, something we have harped on and pointed out numerous times on this site (we exposed that the app was selling its order flow to HFT algorithms as early as 2018).

Meanwhile, Robinhood still appears to be having outage issues, with the app going down as recently as Monday and again this morning.

In response, the company hired former Republican SEC commissioner Dan Gallagher as its top lawyer. Gallagher has years of experience with federal regulation.

“Robinhood is empowering a whole new class of investors, and I think it is critical for us to have a voice in Washington to advocate for our customers and fairer markets,” Gallagher concluded.

Enjoy those IPO shares, Dan. After the Citadel-led IPO of course.

As an alternative to Robinhood, try LevelX @ www.levelx.com

Friday, August 28, 2020

Sunday, August 23, 2020

Friday, August 21, 2020

Thursday, August 20, 2020

Jeffrey Epstein’s Private Banker At Deutsche & Citi Found Swinging From A Rope

Jeffrey Epstein’s private wealth banker, who brokered and signed off on untold multiple millions of dollars in controversial Deutsche Bank and Citibank loans spanning two decades for the convicted pedophile, has died from a reported suicide.

The news of yet another mysterious Epstein-linked death comes shortly after the FBI was seeking to interview the bank executive about loans he approved for Epstein and the indicted child trafficker’s labyrinth of US-based and offshore companies.

The Los Angeles County Medical Examiner confirmed Thomas Bowers died by an apparent suicide by hanging at his home.

Bowers headed the private wealth banking division for Deutsche Bank and signed off on millions in loans to Epstein.

Bowers, prior to taking over the private banking arm at Deutsche Bank, served in the same top position at Citibank, as the head of the bank’s private wealth arm. Citigroup also made massive loans to Epstein, according to records and banking sources who spoke to True Pundit.

True Pundit founder Mike “Thomas Paine” Moore previously headed anti-money laundering for a major Citigroup division during the time frame Citi commenced large loans to Epstein.

“The loans to Epstein were personal and commercial,” Paine confirmed. “The Citi loans I can confirm were for more than $25 million. Some were secured, some were not.”

Did Citi bend its lending rules for Epstein? Paine said that appears “quite likely,” with Bowers and other Citi executives he later recruited to work for him at Deutsche all working to secure the approvals regardless of compliance-related red flags.

And sources said Citi loaned Epstein much more money, eclipsing $100 million and also allowed Epstein to use the bank to send thousands of wire transfers from his accounts. Bowers, who turned up dead just days ago, brokered the loans for Epstein, sources said.

Bowers was the chief of Deutsche Bank’s Private Wealth Management division and worked from the bank’s Park Avenue offices in New York City. At Citi, Bowers served as the chief of the The Citi Private Bank and previously ran Citigroup’s Global Markets and Wealth Management businesses.

And when Bowers left Citi for Deutsche Bank, Epstein followed.

Meanwhile, Epstein stopped making payments on his millions in outstanding Citi loans. But that mattered little because Bowers approved new high-risk loans and credit lines from Deutsche Bank, sources said.

And that relationship with Epstein continued until Bowers left Deutsche Bank in 2015. By that time, Epstein had chalked up untold millions in loans with the help of Bowers who recruited many of his top private wealth top bankers from Citi to Deutsche Bank.

The FBI who was interested in interviewing Bowers, sources confirm. The FBI subpoenaed Deutsche Bank in May for all loans and accounts linked to Epstein and there were many unanswered questions. Deutsche Bank closed out Epstein’s accounts weeks after the bank was served federal subpoenas.

Federal law enforcement officials said the FBI planned to interview all Wall Street wealth fund managers who worked for Epstein. Bowers included.

How much money did Deutsche broker for Epstein? That number to this point has proven elusive. The FBI is not talking, but one executive divulged Epstein had secured more than $60 million from Deutsche Bank’s U.S. and German arms. Likely that number is larger, but at this point the bank is keeping its exposure quiet.

Just like Bowers had brokered for Epstein at Citi, Deutsche also set the convicted pedophile up with over a dozen bank accounts that Epstein employed to receive and send wires and funds.

One banking executive said Bowers had visited Epstein on his private island at least once. Bowers had also visited Epstein in New York and attended social events at his mansion. Federal law enforcement sources did not comment about these new revelations.

However, Citi executives who worked with Bowers said the bank executive maintained an active night life and enjoyed the party circuit.

Epstein also helped bring in a plethora of new business from wealthy associates to Bowers at both Deutsche Bank and Citi, sources said.

“Epstein made Bowers and his financial institutions hundreds of millions of dollars,” one executive said. “It really didn’t even matter that Epstein stiffed Citi for $30 million in defaults because he brought so much new money, new blood in. Citi made far more than it lost.”

Seems like a pattern. The American Banker reports:

Epstein brought lucrative clients into JPMorgan’s private-banking unit and was close to former head Jes Staley, who visited Epstein’s private island as recently as 2015. Leon Black, Apollo Global Management’s billionaire chairman, met with the financier from time to time at the company’s New York offices, and used Epstein for tax and philanthropic advice.

Police reportedly found Bowers hanging from a rope in his California home.

He was 55.

Previous press releases detailing Bowers’ role with the private wealth arm of Deutsche, detailed the division and its target clientele:

Deutsche Bank Private Wealth Management has been serving the interests of wealthy individuals, families and select institutions for more than a century. With offices across the U.S., Deutsche Bank’s Private Wealth Management business division provides a variety of customized solutions to private clients worldwide including traditional and alternative investments, risk management strategies, lending, trust and estate services, wealth transfer planning, family office services, custody and family and philanthropy advisory.

Private Wealth Management includes the U.S. Private Bank and Deutsche Bank Alex. Brown, the private client services division of Deutsche Bank Securities Inc., the investment banking and securities arm of Deutsche Bank AG in the United States and a member of NYSE, FINRA and SIPC.

This story is developing.