David Smith won’t soon forget his 38th-birthday party.

Standing on the grounds of an estate in Kingston, Jamaica, in front of a throng of some 200 investors in his foreign-exchange-trading fund, Smith listened sheepishly as his mentor and hero, Jared Martinez, compared him to Moses leading his flock to the promised land. “I wanted to buy something like the staff that Moses used to carry,” said Martinez, whose remarks have been preserved on video. “David has freed so many people down here,” Martinez told the crowd, referring to Smith’s 10 percent monthly returns. “David, we’d like to say thank you for being our Jamaican Moses.”

Smith, now 46, recalls the moment as fraught with mixed emotions, Bloomberg Marketsreports in its June 2015 issue. The charismatic Martinez, 59, who runs the oldest and largest trading school in the U.S. serving the lightly regulated $400 billion–a-day retail forex market, had grown into a trusted father figure for Smith. Under Martinez’s tutelage, Smith had succeeded in expanding his fund and increasing his personal fortune enough to afford a $2 million seaside mansion and a Learjet. Yet Smith knew he was no Moses. His fund was a fraud.

Three years later, in August 2010, U.S. prosecutors alleged Smith and his co-conspirators laundered more than $200 million of investor money through multiple U.S. bank accounts created by Martinez and two of his sons. Those transactions were the basis of 19 counts of money laundering and conspiracy against Smith, with Martinez and his sons identified as unindicted co-conspirators. Smith was also charged with four counts of fraud.

David Smith, now held in Turks and Caicos, is fighting extradition to the U.S., where he would serve out a 30-year prison sentence.

David Evans

Smith sees himself as a victim—a con man duped by another con man who proved more savvy. Smith met with aBloomberg Markets reporter in January in a detention facility on the Turks and Caicos island of Providenciales, a tourist mecca for beachgoers and snorkelers. He says he admitted guilt as part of aplea bargain with U.S. prosecutors filed in March 2011, expecting to testify against Martinez and his two sons, Isaac, now 31, and Jacob, now 34. He had already been convicted and sentenced to 6½ years in a Turks and Caicos prison and was hoping for leniency.

The Martinez family was never charged and in August 2011, a U.S. federal judge in Orlando sentenced Smith to a concurrent 30-year term. Smith is fighting extradition to the U.S. Martinez’s brokerage was fined $250,000 by the National Futures Association, a self-regulatory group, for failing to investigate Smith’s operation.

“Once I decided I’d plead guilty, there was no holding back,” Smith says, locked up just a few miles from the turquoise waters and seaside villa where he often entertained the Martinez family. “I went all the way. I did everything they asked me to do. I got nothing in return.”

Smith doesn’t deny that he committed a crime. He has confessed to defrauding some 6,000 people out of $220 million when his Ponzi scheme collapsed. He just thinks that if he has to take up residence in a U.S. prison, he should have gotten a reduced sentence in exchange for his cooperation.

Ten years ago, Martinez accepted Smith as a student at his forex-trading school outside Orlando. Martinez then followed Smith to his native Jamaica to sell classes to his investors. In classic Ponzi-scheme fashion, Smith used money from new investors to pay off his existing clients, much of it laundered through Martinez-controlled accounts, according to prosecutors. Smith contends Martinez outsmarted prosecutors by claiming he and his sons had no knowledge that they were laundering money for Smith. Martinez and his two sons declined to comment for this story. “I really felt this man was genuine, that he loved me like a son,” says Smith. “He just threw me under the bus.”

Smith’s plea agreement describes wiring more than $100 million of investor funds from Turks and Caicos to I-Trade FX, a brokerage firm he owned in Florida with the Martinez family. Cash flowed through JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and other banks before circling back to the Caribbean. Almost no foreign exchange was traded.

“It was a huge washing machine,” says Assistant U.S. Attorney Bruce Ambrose, who prosecuted Smith for money laundering. Yet he didn’t seek to indict Martinez family members he identified as co-conspirators. Ambrose would not explain why. The U.S. Attorney’s office later issued a statement to Bloomberg Markets saying it stands by its decision not to prosecute the family, saying Smith did not fully cooperate. Moreover, “the statute of limitations has long since expired for charging anyone who may have been involved in criminal activity with Mr. Smith,” it said.

Law enforcement agents from the U.S., Jamaica, and Turks and Caicos say that the Martinez family actively participated in Smith’s criminal enterprise, and they were stunned that U.S. prosecutors never charged the father and sons.

“It was a great case,” says Louis Skenderis, a special agent with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, who spent three years investigating the family’s role in helping Smith move cash in and out of the U.S. “We brought David to Florida as a witness against the Martinezes, and he agreed to plead guilty as part of the deal.”

“I think David Smith is just a pawn,” says Janice Holness, executive director ofJamaica’s Financial Services Commission, interviewed at her office in Kingston. “Smith is a crook and got what he deserves, but there are bigger fish. He’s taking a fall for these people, including Jared Martinez.”

Smith turned to Martinez, founder of a forex-trading school, after his fund tanked. He says Martinez was like a father to him.

Reed Young

Martinez has said that’s simply not true. “It’s difficult to be falsely accused of anything,” he said in an October 2011 press release, two months after Smith was sentenced. “And it is unfortunate that we were perceived to be guilty by association.”

Martinez, whose Florida license plate reads “FX Chief,” says he has earned millions of dollars trading and running forex classes at his Market Traders Institute, which he founded in 1994 and which employs 115 workers. Dozens of telemarketers hawk his classes. He says he’s taught 30,000 students a formula for making consistent profits with MTI’s Ultimate Traders Package, which sells for $7,995. Yet, in an interview withBloomberg Markets last year, Martinez estimated no more than half his customers make back trading what they spend on their MTI tuition.

Martinez also said the retail forex industry is cleaner now than it was a decade ago. “Ten years ago, it was the Wild West,” he said. “Ponzi schemes were running rampant.” (See “The Currency Casino,” December 2014.)

Smith, dressed in blue gym shorts and a baggy gray T-shirt in the Providenciales police station, described how he turned from a legitimate if failed forex trader to a criminal who put all his hopes in one friendship. He grew up in a middle-class family in Kingston, the son of two high school science teachers. When he was 24, Smith took a job as a trader for a financial firm called Jamaica Money Market Brokers. While working there, he also earned a B.S. in business from Nova Southeastern University’s Jamaica campus. Two years later, in 2003, Smith was let go from the firm for what its marketing manager Kerry-Ann Stimpson describes as a breach of the firm’s “core values.” She declined to elaborate.

Smith set up a forex-trading company in 2005 called Olint, short for Overseas Locket International. Olint didn’t start out as a Ponzi scheme, he says. Smith just wasn’t very good at trading. “I lost a lot of money,” he says. “I could have declared losses and given back what was left, but I didn’t want to do that.” Instead, according to his plea agreement, he told clients that Olint accounts were earning returns averaging 10 percent a month. When the word spread, money from middle- and upper-class Jamaican investors poured in.

The losses, though, were piling up. “I stopped trading totally and started looking for education,” Smith says. Searching the Web, he discovered Martinez’s MTI. Smith flew to Orlando in April 2005 to take MTI’s four-day course, which promised to show students how to predict currency-trading patterns with “technical analysis”—reading and interpreting charts of, say, the dollar versus the euro’s past behavior.

When Martinez, who was born on the Blackfeet American Indian reservation in Montana, learned that Smith ran his own investment firm, he and Isaac approached Smith about forming a partnership, Martinez later told regulators. In February 2006, Smith invested $1 million to help fund I-Trade FX, the Martinez family’s new Florida-based forex brokerage.

Smith’s operation in Jamaica, run from a shopping mall storefront in downtown Kingston, was bustling. Olint was organized as an exclusive private club that accepted only new investors referred by members. Early investors received monthly e-mailed statements showing returns as high as 12 percent. To manage withdrawals, Smith says, he would decide returns to be paid each month. He would drag out payments during periods when requests for withdrawals increased. If plenty of new money was coming in, he would lower the return for that month. If withdrawals were rising, he would increase it in an effort to hold on to investors.

In March 2006, Smith’s scheme nearly unraveled. Following a tip by an investment banker, police and agents from Jamaica’s Financial Services Commission executed search warrants at Olint’s office, hauling off documents, cash, and computers, including a Bloomberg terminal. A cease-and-desist order banning Olint from opening new accounts soon followed from the FSC.

Smith invited nervous investors to pull out even though he knew he didn’t have enough to pay everyone. The gambit worked, quashing press reports that Olint was a Ponzi scheme. “The money flew back in,” quickly tripling Olint’s assets, Smith says. “If I’d gotten requests for another $1.1 million, I couldn’t have paid it,” he says.

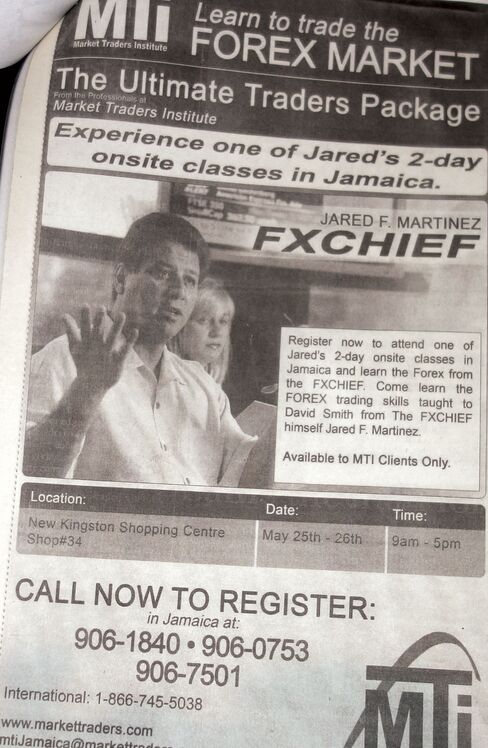

Advertising in Jamaican newspapers, Martinez invited investors to learn the same forex-trading skills he taught Smith.

No criminal charges were filed against Smith in Jamaica. That might have to do with the money he was spreading around the island in campaign contributions for local politicians—many of whom were also investors. Smith gave away more than $8 million of client money, according to court documents, including $5 million to the Jamaica Labour Party and $2 million to its rival, the Jamaican People’s National Party, which now controls the government. While the JLP says only its candidates received contributions from Smith, the PNP acknowledges receiving direct contributions.

Peter Bunting, the investment banker who brought the case to the attention of the police and who now serves as Jamaica’s national security minister, says Olint investors represented a who’s who of Jamaica, including politicians, businessmen, and judges. “The enmeshment with the official system was very substantial,” Bunting said at his Kingston office in February.

Olint needed to find an alternative to the Jamaican bank accounts that had been used to receive investor deposits, according to Smith’s plea agreement. A week after the cease-and-desist order, Martinez and his son Isaac, who served as president of the brokerage, asked the NFA to license I-Trade FX. The regulator awarded I-Trade a brokerage license in August 2006, and Smith began transferring funds to the firm.

Martinez, meanwhile, began conducting forex-trading seminars in Jamaica, capitalizing on the island’s buzz around Smith and Olint. Dominic Azan, who became MTI’s Jamaica sales manager, still remembers the electricity he felt in the summer of 2006 listening to Martinez onstage, his audience in thrall, as he talked up the trading success of MTI graduates. Azan felt reassured about the $1 million he and his family had invested in Olint— nearly all of which was later lost. “Who didn’t want to be part of it? Here’s the guru, the FX Chief himself, the guy who taught David how to trade,” says Azan, who recalls admiring Martinez’s Breitling watch collection and gleaming Rolls-Royce.

Martinez made the most of his opening: “TURN $2,000 INTO $10,000 in Twenty Days. Learn How!” urged an MTI advertisement in a Jamaican newspaper in September 2006. Students lined up for classes paid for by Smith: Olint paid $1.9 million to MTI for investors’ seminars, according to a report prepared for the Turks and Caicos government by PricewaterhouseCoopers. The result was a faithful following who believed so deeply in Smith and Martinez that they were willing to entrust their life savings to the pair. Smith says there is no doubt Martinez was aware of his scam. “He knew the money wasn’t being traded, and yet I was paying people 10 percent a month,” says Smith. “He knew it was a lie.”

Martinez later testified before the NFA that he was aware of David’s regulatory problems in Jamaica and had had more than 500 conversations about them. Still, he said he found nothing suspicious about Smith before the Ponzi scheme collapsed in 2008. “We did a substantial amount of due diligence,” Martinez told the NFA, which began a probe of I-Trade FX in 2007. He said he never asked to see proof of Smith’s returns. “Some people, especially Jamaicans, they can be very offended by that,” he explained.

Regulators have suggested Martinez should have known better. “Advertised returns of the magnitude Smith claimed are often fraudulent,” the NFA wrote in an April 2009 ruling. “I-Trade should have questioned them.”

Smith fled Jamaica’s regulatory heat in the summer of 2006, relocating 400 miles (644 kilometers) northeast to Turks and Caicos, where he used investors’ money to buy his family’s waterfront home on Providenciales. He also set up two new investment clubs to raise cash, which he wired to I-Trade in Florida.

In March 2007, the Martinez family opened JIJ Investments, a hedge fund incorporated in Florida as “an alternative depository” outside the purview of the NFA, according to Smith’s plea agreement. “Unindicted co-conspirators are the listed directors of the firm,” according to the criminal complaint. JIJ Investments’ directors were Jared, Isaac, and Jacob.

The Martinez family wired $76 million from I-Trade to its JIJ accounts at JPMorgan, Bank of America, and Wachovia Bank, later purchased by Wells Fargo. Each wire transfer was described as money laundering in the criminal complaint against Smith. None of the banks was accused of any wrongdoing.

While Smith operated from Turks and Caicos, the families remained close, according to NFA testimony by Isaac, who often stayed at Smith’s island house. “His kids called me Uncle Isaac,” he said. “I would fly with him on his private jet.” Smith says he and Isaac enjoyed deep-sea fishing for yellowtail snapper. Isaac told the NFA that he never knew about Smith’s illegal activities.

The good times ended in July 2008 when the Turks and Caicos police executed a search warrant at Smith’s home and office in Providenciales. Olint and its victims were the talk of the island.

Dominic’s father, Khaleel Azan, says he and Martinez often dined together. He says he appealed to Martinez in late 2007, when he couldn’t withdraw the family’s $1 million from Olint. “Jared told me, ‘I promise, we have over $100 million from David. I’ll make sure you get your money.’” But the family’s investment was lost.

Chris Walker, an obstetrician in Orlando, says Martinez introduced Smith as 'the best student he's ever had.'

Jeffrey Salter

Chris Walker, an Orlando obstetrician, also lost more than $1 million investing with Olint, and his father, Kenneth Walker, lost $1.5 million—his life savings. Chris Walker met Smith at a forex-trading seminar conducted by Martinez in Jamaica. He recalls Martinez ushering Smith up onto a podium in front of hundreds of attendees, at a hotel in Ocho Rios. “Jared introduced David like the Messiah, as the best student he’s ever had,” says Walker. He says he poured more cash into Olint after the seminar. “Jared is a very effective salesman,” Walker says.

Walker later sued Smith, as well as Martinez and his sons, in Florida state court, alleging fraud, but says he gave up after running out of money. “It boggles my mind why the Martinez family did not get indicted,” he says. “Why aren’t the co-conspirators behind bars?”

Smith was arrested in February 2009. In April 2009, I-Trade was fined $250,000 by the NFA for failing to sufficiently investigate suspicious activity by several customers, including Smith. A month later, I-Trade shut down, though Martinez’s forex school is still in business. In 2010, Isaac, as president and compliance officer of the firm, wasfined an additional $50,000 for failure to supervise. Jacob, meanwhile, was bannedfrom the industry for three years in 2012 and ordered to pay a $150,000 fine should he seek to return to the industry.

Smith didn’t get off so easily. In 2010, he was convicted of Ponzi-related crimes in Turks and Caicos. In March 2011, he pleaded guilty in a federal court in Orlando, resulting in his 30-year prison term.

“I’m really shocked the Martinez family has escaped U.S. prosecution for a massive money-laundering exercise,” says Mark Knighton, the retired head of the Turks and Caicos financial crimes unit, who ran the island’s investigation of Olint. “We certainly had the evidence.”

On Jan. 23, in a surprise to the U.S. Department of Justice, Smith was released two years early from his Turks and Caicos prison cell. He spent that night with his wife, Tracy, and their four children, ages 5 to 13. It was the first time in four years the family had been together. “I am enjoying the moment right now,” he said in a telephone interview amid the excited screams of his kids. “I don’t know when they’re going to come and get me.”

Less than 24 hours later, Smith was taken back into custody at the request of the Justice Department. The U.S. will present its case for extradition at a hearing on Providenciales on June 5. It could be a long time before David Smith goes home again.

This story appears in the June 2015 issue of Bloomberg Markets.