With a seismic overhaul of the $2.6 trillion money-market industry weeks away from kicking in, money managers are bracing for a last-minute exodus of as much as $300 billion from funds in regulators’ cross hairs.

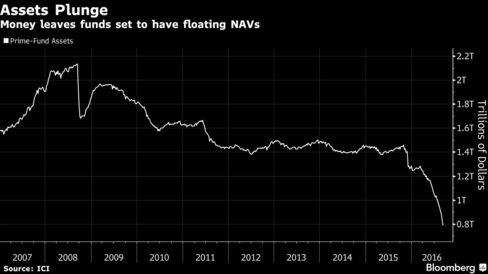

Prime funds, which seek higher yields by buying securities like commercial paper, are at the center of the upheaval. Their assets have already plunged by almost $700 billion since the start of 2015, to $789 billion, Investment Company Institute data show. The outflow has rippled across financial markets, shattering demand for banks’ and other companies’ short-term debt and raising their funding costs.

The transformation of the money-fund industry, where investors turn to park cash, is a result of regulators’ efforts to make the financial system safer in the aftermath of the credit crisis. The key date is Oct. 14, when rules take effect mandating that institutional prime and tax-exempt funds end an over-30-year tradition of fixing shares at $1. Funds that hold only government debt will be able to maintain that level. Companies such as Federated Investors Inc. and Fidelity Investments, which have already reduced or altered prime offerings, are preparing in case investors yank more money as the new era approaches.

“All managers, like ourselves, are positioning around the uncertainty of the exact magnitude of the outflows,” said Peter Yi, director of short-term fixed income at Chicago-based Northern Trust Corp., which manages $906 billion.

$300 Billion

While Yi sees the additional outflow from prime-fund investors potentially reaching $200 billion in the next 30 days, TD Securities predicted in a Sept. 7 note that it may tally as much as $300 billion.

Yi is preparing by shortening his funds’ weighted average maturity and avoiding short-term debt that matures beyond September. He’s not alone. For the biggest institutional prime funds tracked by Crane Data LLC, the weighted average maturity of holdings fell to an unprecedented 10 days as of Sept. 12. It’s not just floating net-asset values that investors are avoiding. Prime funds can also impose restrictions such as redemption fees.

Amid the tumult, money-fund assets have held steady because most of the cash leaving prime and tax-exempt funds has streamed into less risky offerings focusing on Treasuries and other government-related debt, such as agency securities and repurchase agreements. These funds are exempt from the new rules, which the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission issued in 2014.

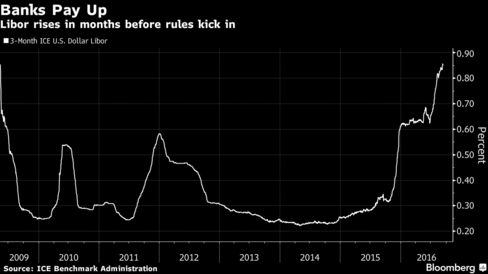

A major repercussion of the flight from prime funds is that there’s less money flowing into commercial paper and certificates of deposit, which banks depend on for funding. As a result, banks’ unsecured lending rates, such as the dollar London interbank offered rate, have soared. Three-month Libor was about 0.85 percent Wednesday, close to the highest since 2009.

Libor may stabilize after mid-October because prime funds may begin to increase purchases of bank IOUs, although the risk of a Federal Reserve interest-rate hike by year-end will keep it elevated, said Seth Roman, who helps oversee five funds with a combined $3.2 billion at Pioneer Investments in Boston.

“You could picture a scenario where Libor ticks down a bit,” Roman said. But “you have to keep in mind that the Fed is in play still.”

Financial firms paying higher rates to attract investors to their IOUs will push three-month Libor to about 0.95 percent by the end of September, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Although bank funding costs are rising, it isn’t a signal of financial strain as in 2008, said Jerome Schneider, head of short-term portfolio management at Newport Beach, California-based Pacific Investment Management Co., which oversees about $1.5 trillion.

“This is not a credit stress event, it’s a credit repricing due to systemic and structural changes,” he said.

The market for commercial paper has shrunk about 50 percent from its $2.2 trillion peak in 2007, pushing financial firms to diversify funding sources -- choosing longer-term debt and loans in foreign currencies.

At least $269 billion in commercial paper and certificates of deposits held by prime funds will come due before Oct. 14 and most issuers of that debt will need to find financing outside the money-fund industry, JPMorgan predicts.

The hubbub in money markets has its roots in a crucial episode of the financial crisis -- the demise of the $62.5 billion Reserve Fund, which became just the second money fund to lose money, or “break the buck.” The event contributed to the global freeze in credit markets and pushed the Treasury Department to temporarily backstop almost all U.S. money funds.

With the Fed’s target rate still not far from zero, money-fund investors looking to pad returns may overcome their aversion to prime funds. Institutional prime funds’ seven-day yield was 0.24 percent as of Sept. 12, compared with 0.17 percent for government funds, according to Crane Data.

“You’ll see the prime-fund space continue to shrink until we hit mid-October,” said Tracy Hopkins, chief operating officer in New York at BNY Mellon Cash Investment Strategies, a division of Dreyfus Corp.

“After that,” she said, “I would not be surprised to see assets return, once customers get accustomed to the floating NAVs and want to earn incremental yield over government money-market funds.”