Written by Jan Nieuwenhuijs for Voima Insight,

The spread between the New York futures and London spot gold price was initially caused by logistics and manufacturing constraints, and likely persists because of credit restrictions.

If you read into the economics of commodities, much of it is about geography. The Corona crisis and its effects on global aviation has disrupted large shipments of gold, and created price discrepancies geographically. Normally, bullion is transported in passenger planes, but as those have stopped flying, there is more friction in bullion logistics. Partially, this created the spread between the futures gold price in New York and the London spot price. In my view, the spread persists because arbitragers don’t have enough access to funding, and demand in New York remains elevated.

How it Started

On March 14, 2020, President Trump started curbing passenger flights between Europe and the US. Including those from Switzerland, where the four largest gold refineries of the world are located. This didn’t happen in isolation. Passenger flights all over the world were being curbed. One of the most important airports in London—home of the largest gold spot market by trading volume—is Heathrow. Since March 10, 2020, arrivals at Heathrow started declining from 600 flights per day, to 250 two weeks later.

On March 23, 2020, three refineries in Switzerland where temporarily shut down due to the coronavirus. Reuters reported:

Three of the world’s largest gold refineries said on Monday they had suspended production in Switzerland for at least a week after local authorities ordered the closure of non-essential industry to curtail the spread of the coronavirus.The refineries - Valcambi, Argor-Heraeus and PAMP - are in the Swiss canton of Ticino bordering Italy, where the virus has killed more than 5,000 people in Europe’s worst outbreak.

Normally, airlines transporting gold and refineries manufacturing small bars from big bars, or vice versa, keep the price of gold products across the globe in sync. If supply and demand for gold in one region is out of whack relative to another, arbitragers step in (buy low, sell high). But with planes not flying and refinery capacity crippled, everything changed.

Making delivery at the New York futures market, the COMEX, wasn’t that simple anymore. As we all know, shorts and longs on the COMEX are mostly naked. They either don’t have the metal to make delivery (shorts), or don’t have the money to take delivery (longs). In normal circumstances this isn’t a problem because neither shorts or longs are interested in physical delivery. They trade futures to hedge themselves or speculate. However, when sourcing small bars from Switzerland—only 100-ounce and kilobars are eligible for delivery of the most commonly traded COMEX futures contract—became “more difficult,” the shorts became nervous.

Likely, after the refineries closed, shorts wanted to close their positions as soon as possible to avoid making delivery. Closing a short position is done by buying long futures to offset one’s position. These trades were driving up the price in New York, and the spread was born.

Usually, such a spread is closed by arbitragers (often banks). They buy spot (London) and sell futures (New York) until the gap is closed. If necessary, these arbitragers hold their position until maturity of the futures contracts, and make delivery to lock in their profit. But because flights were cancelled and refineries were shut down, the “arb” was risky and the spread didn’t close.

Bullion Banks Losing Money Through EFPs

Bullion banks often have a long spot position in London and are short futures on the COMEX. When a refinery in Switzerland, for example, casts big bars (400-ounce) and sells them to a bullion bank in London, the bank hedges itself on the COMEX. This makes the bank long spot and short futures.

Exchange For Physical (EFP) allows traders to switch Gold futures positions to and from physical [spot], unallocated accounts. Quoted as dollar basis, relative the current futures prices, EFP is a key component in pricing OTC spot gold.

(The London Bullion Market is an OTC market.)

An EFP is usually a swap between a futures and a spot position. In banking jargon the word “EFP” also refers to, (i) having a position in both markets, and (ii) the spread in general (because the price of the EFP is equal to the difference in price between New York futures and London spot). A bullion bank that is “short EFP” is long spot and short futures.

As mentioned, banks are most of the time short EFP. When the spread widened their short EFP starting bleeding. To avoid further losses, some banks “were forced to cover,” which added fuel to the fire. (It can also be the banks themselves started the spread to widen.) Many banks suffered severe losses.

Currently, most refineries in Switzerland have reopened. So, why does the spread persist? After all, arbitragers can hire planes to transport gold to wherever. On April 30, 2020, the spread was still $15 dollars per troy ounce.

Because I couldn't figure this out myself, I asked John Reade, Chief Market Strategist of the World Gold Council, and Ole Hansen, Head of Commodity Strategy at Saxo Bank, for their views.

Reade wrote me:

I guess for two reasons: firstly, banks and traders probably still have large EFP positions that they haven’t been able to cover. And secondly, I doubt that risk officers and banks are prepared to allow large EFP positions to be run, so the usual arbitragers of this market cannot add to their positions, flattening the spread.

Which is in line with what Hansen wrote me:

While COMEX has now allowed the delivery of 400oz bars (the most popular bar size in London) and raised spot positions limits the problem has not gone away. This means that the mechanism that should balance the gold market still isn’t functioning correctly despite improving underlying physical conditions.Market makers [banks] have suffered major losses last month and as they tend to natural short the EFP (long OTC, short futures) the risk appetite and ability to drive it back to neutral has for now been disrupted.

Banks lost so much money, they are cautious not to lose more. They don’t access funds to close the spread.

Conclusion

Generally, just the threat of delivery keeps markets in line as well. Any trader that sees an arbitrage opportunity can take position without the intention of making/taking delivery, in the knowledge that New York futures and London spot will converge. Now this certainty doesn’t prevail, traders are cautious. If they take positions but the spread widens, they lose.

Another reason why the spread can persist, is because of strong demand in New York. Speculators that reckon the price of gold will go up will buy long futures, increasing the spread. Normally, this type of demand is smoothly translated into the spot market by arbitragers without increasing the spread. But not now.

In a nutshell, I think that logistics and credit restrictions prevent the spread to close. However, if anyone has a better analysis please comment below.

Addendum

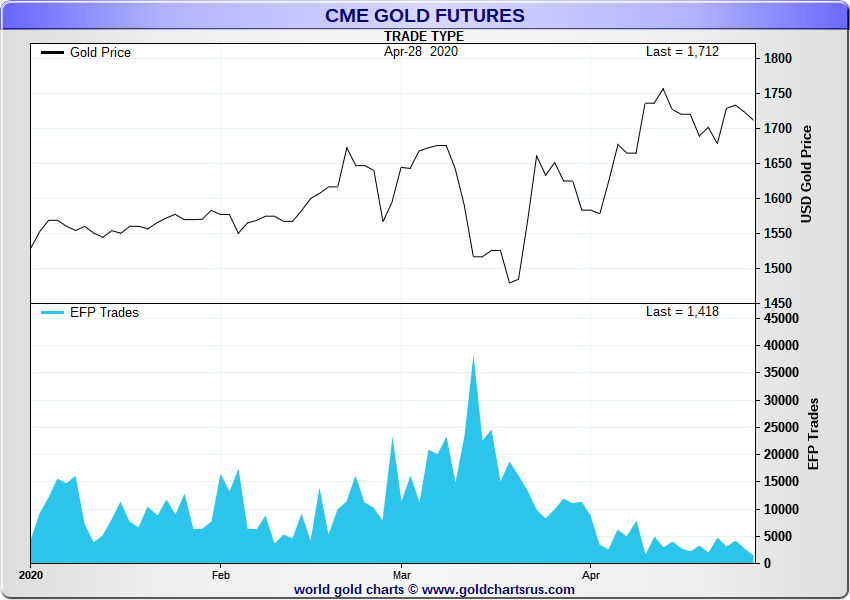

It can be, as John Reade wrote me, “banks and traders probably still have large EFP positions that they haven’t been able to cover.” I noticed on Nick Laird’s website Goldchartrus.com that EFP volume cleared through CME’s ClearPort is decreasing since early March, to levels not seen in a long time.

Perhaps this is a reflection of a market that is slowly trying to heal itself. Perhaps when all losses have been crystalized, banks, or other financial entities with sufficient firepower to hire planes etc., will close the spread.

Another possibility is that when the new COMEX futures contract—that can be delivered in 400-ounce bars—becomes active, the spread closes. At the time of writing, the open interest of this contract is virtually zero. Time will tell.