It is often said that before the Civil War, the United States “are,” but after the War, the United States “is.” This is a reference to the formerly theoretically sovereign nature of each state as compared to “one nation, indivisible.”

More than just the theoretic sovereignty of the individual states, the territory now comprising the U.S. has a rich history of sovereign states outside the control of the federal government. Some of these you’ve almost certainly heard of, but a lot of them are quite obscure. Each points toward a potential American secession of the future.

Vermont Republic (January 15, 1777 – March 4, 1791)

Current Territory: The State of Vermont

The earliest sovereign state in North America after the Revolution was the Vermont Republic, also known as the Green Mountain Republic or the Republic of New Connecticut. The Republic was known by the United States as “the New Hampshire Grants” and was not recognized by the Continental Congress. The people of the Vermont Republic contacted the British government about union with Quebec, which was accepted on generous terms. They ultimately declined union with Quebec after the end of the Revolutionary War, during which they were involved in the Battle of Bennington, and the territory was accepted into the Union as the 14th state – the first after the original 13.

The country had its own postal system and coinage, known as Vermont coppers. These bore the inscription “Stella quarta decima,” meaning “the 14th star” in Latin. They were originally known as “New Connecticut” because Connecticut’s Continental representative also represented Vermont Republic’s interests at Congress. However, the name was changed to Vermont, meaning “Green Mountains” in French.

Their constitution was primarily concerned with securing independence from the State of New York. Indeed, the state was known as “the Reluctant Republic” because they wanted admission to the Union separate from New York, Connecticut and New Hampshire – not a republic fully independent of the new United States. The genesis of the issue lay with the Crown deciding that New Hampshire could not grant land in Vermont, declaring that it belonged to New York. New York maintained this position into the early years of the United States, putting Vermont in the position of trying to chart a course of independence between two major powers.

The Green Mountain Boys was the name of the militia defending the Republic against the United States, the British and Mohawk Indians. They later became the Green Mountain Continental Rangers, the official military of the Republic. The “Green Mountain Boys” is an informal name for the National Guard regiment from the state.

In 1791, the Republic was admitted to the Union as the 14th state, in part as a counterweight to the slave state Kentucky. The 1793 state constitution differs little from the constitution of the Republic. The gun laws of Vermont, including what is now known as “Constitutional Carry,” are in fact laws (or lack thereof) dating back to the days of the Green Mountain Republic. The constitution likewise included provisions outlawing adult slavery and enfranchising all adult men.

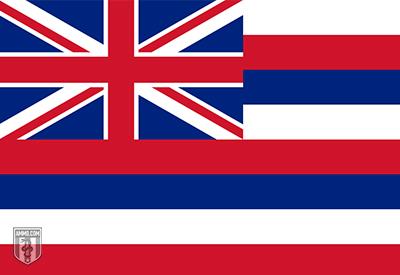

Kingdom of Hawaiʻi / Republic of Hawaii (May 1795 – August 12, 1898)

Hawai’i as a sovereign state is almost as old as the United States itself. Its origins were in the conquest of the Hawai’ian island. Western advisors (and weaponry) played a role in the consolidation of several islands into a single kingdom under Kamehameha the Great, who conquered the islands over a period of 15 years. This marked the end of ancient Hawai’i and traditional Hawai’an government. Hawai’i was now a monarchy in the style of its European counterparts. It was also subject to the meddling of great powers France and Britain, in the same manner of smaller European states.

The Kingdom was overthrown on January 17, 1893, starting with a coup d'état against Queen Liliʻuokalani. The rebellion started on Oahu, was comprised entirely of non-Hawai’ians, and resulted in the Provisional Government of Hawaii. The goal was, in the manner of other states on our list, quick annexation by the United States. President Benjamin Harrison negotiated a treaty to this end, but anti-imperialist President Grover Cleveland withdrew from it. The failure of annexation led to the establishment of the Republic of Hawaii on July 4, 1894.

In 1895, the Wilcox rebellion, led by native Hawai’ian Robert William Wilcox, attempted to restore the Kingdom of Hawai’i. The rebellion was unsuccessful and the last queen, Liliuokalani, was put on trial for misprision of treason. While convicted, her prison term was nominal. She was sentenced to “hard labor,” but served it in her own bedroom and was eventually granted a passport to travel to the United States, which she used to extensively lobby against annexation.

When pro-imperialist President William McKinley won election in 1896, the writing was on the wall. The Spanish-American War began in April 1898, with the Republic of Hawaii declaring neutrality, but weighing in heavily on the side of the United States in practice. Both houses of Congress approved annexation on July 4, 1898, and William McKinley signed the bill on July 7th. The stars and stripes were raised over the island on August 12, 1898. And by April 30, 1900, it was incorporated as the Territory of Hawaii.

Republic of West Florida (September 23, 1810 – December 10, 1810)

The Republic of West Florida, now a part of Eastern Louisiana, was a short-lived republic resulting from the complicated and competing claims as to where the boundary between the French-controlled area of Louisiana and the Spanish-controlled territory of Florida actually sat. Great Britain also had a competing claim, which it ceded to Spain at the end of the Revolutionary War.

The overlapping claims are so complicated, that repeating them does little save for muddying the waters. The important fact is that there was an influx of Americans into the region in the early years of the 19th Century. Some of these were Loyalists fleeing the United States, but for the most part it was just Americans seeking what most Americans were at that time – land. This, plus the imprecise nature of international boundaries, led to an escalating series of military engagements between the United States on the one hand, and Britain and Spain on the other.

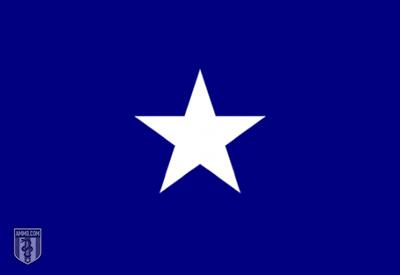

Everything ultimately came to a head in 1810. Secret meetings conspired against Spanish authorities. Three conventions for an independent republic were held in the open. Independence was declared and a capital organized at St. Francisville. On September 23, 1810, armed independence forces stormed Fort Carlos in Baton Rouge, killing two Spanish soldiers. There was a single battle, but it was decisive – The Republic of West Florida was a reality. The flag, on which the later Bonnie Blue Flag of Southern Secessionists was based, was flying freely.

President James Madison saw this as an opportunity: He could annex the district, securing territory the United States had its eyes on for years. Technically, Madison was not authorized to use American military forces in the region without Congressional approval. What’s more, Congress was not in session to provide such approval. But Madison acted anyway, and while there were certainly complaints, none of them amounted to much.

On October 27, 1810, President Madison stated that “possession should be taken” and dispatched Orleans Territory Governor William C. C. Claiborne to do so. The capital city of St. Francisville surrendered to the United States Army on December 6th, while Baton Rouge fell four days later. The primary objection to annexation from West Floridians is that they sought admission as a separate state, or at least wanted to see their elected officials incorporated into the power structure. This led to rebels once again raising the Republic’s flag on March 11, 1811, with Governor Claiborne dispatching troops. Spain did not drop their claim until American annexation of Florida in 1819.

The Republic of West Florida Constitution closely resembled that of the United States, with a bicameral legislature and three branches of government. The head of state was the governor, who was chosen by the legislature as a whole. “Republic of West Florida” is a historiological name – the official name of the country was the Republic of Florida. Today the region is known as the Florida Parishes of Louisiana.

Republic of Texas (March 2, 1836 – February 19, 1846)

The Republic of Texas is perhaps the most famous and historically significant sovereign state incorporated in the territory of the United States. The existence of the Republic of Texas was the driving force of a nearly two-year war between the United States and Mexico – and the near doubling of American territory all the way out to the Pacific Ocean, as well as the creation of a second republic on American territory.

The Republic of Texas was also the longest-lived of the American sovereign republics, lasting just two weeks shy of 12 years. Annexation as a state was by no means a foregone conclusion for the outset. The State of Texas still retains the prerogative to separate into five states without the consent of the federal government – an increase of eight Senators for the region.

We have covered the Texas Revolution extensively in our guide on the history of the Gonzales Flag. However, some background about how the Texians (as they were known) arrived in Texas is worth getting into. There is, much as the case with Florida, an extensive history of competing claims in the region. The important thing is that during the Mexican War of Independence, many Americans fought on the side of Spain as filibusters. 130 Americans of the Republican Army of the North became disillusioned with the Spanish government and attempted to form an abortive Republic of Texas in 1813, but were summarily crushed. Many of the veterans of the Battle of Medina became leaders in the Texas Revolution to come, and indeed signatories of the Texas Declaration of Independence.

The Republic of Texas is distinguished not only by being the longest-lasting state on our list, but also the most widely recognized. Andrew Jackson was the first United States President to recognize the breakaway nation, appointing a chargè d’affairs in March 1837. The French Legation was built in 1841, and is still the oldest frame structure in the state capital of Austin. Other countries to officially recognize Texas in an official, diplomatic manner include Belgium (freshly independent in its own right), the Federated Republic of Central America, France, the Hanseatic Cities of the Holy Roman Empire, the Netherlands, the Russian Empire and the Republic of the Yucatan, itself a breakaway republic from Mexico. The Republic likewise enjoyed strong trade relations with Denmark and the United Kingdom. Mexico never recognized Texas independence, considering it a renegade province that would eventually be reintegrated into Mexican territory.

Annexation by the United States was always a topic looming large in both Texas and United States politics. The overwhelming majority of Texians saw themselves as Americans, seeking union with the mother country. In the United States, the issue was politically thorny both because of the legality of slavery in the Republic (America at that time was unofficially governed by the Missouri Compromise, which sought to maintain a delicate balance between free and slave states) and relations south of the border. Indeed, the national leadership of both the Democrats and the Whigs opposed the annexation of Texas on some combination of each of these grounds.

The first administration to pursue the matter seriously was President John Tyler, who had been expelled from his political party and was an independent. He secured an annexation treaty in April 1844. The treaty was then sent to the Senate, where the terms were made public. Texas Annexation became one of – if not the – defining issue of the 1844 election. Southern delegates were able to deny popular former President Martin Van Buren the nomination on the grounds that he opposed annexation. This was, strictly speaking, not true. Van Buren simply opposed annexation without due care for Mexican and free state sensibilities. Indeed, Van Buren did not even fully oppose a military option to take control of Texas. James K. Polk won the Democratic nomination with the explicit backing of former President Jackson on a platform of Manifest Destiny in Texas.

In June 1844, the Whig-majority Senate voted down the annexation treaty. And by December of that year, after an anemic re-election bid (he dropped out of the race in August), Tyler obtained approval of the treaty by simple majority of both houses of Congress. He signed this bill in March 1845, as one of the final acts of “His Accidency” as president – and Texas ratified their side of the agreement, with new President Polk signing the bill in December 1845.

The Republic of Texas became the 28th state on February 19, 1846. A dispute over the full extent of the Republic ultimately led to the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848.

Republic of the Rio Grande (January 17, 1840 – November 6, 1840)

While the majority of the ephemeral Republic of the Rio Grande was not on what is now American territory, it’s worth discussing as a sister republic of the Republic of Texas.

Texas was conflicted about how to relate to the Republic of the Rio Grande. Its benefit was to create a buffer state between the Republic of Texas and Mexico. On the other hand, Texas often took pains to not antagonize its neighbor to the south. While Texas pursued an official policy of neutrality, it unofficially encouraged men to enroll in the volunteer military of the Republic of the Rio Grande, and to send military aid where possible.

After a single battle in Saltillo, the territory was peacefully reintegrated into Mexico (who assumed the country’s debts), with no reprisals against the leadership of the Republic. The Republic of the Rio Grande Museum currently sits in Laredo, while the Laredo Morning Times includes the flag of the Republic on its masthead, alongside the traditional six flags over Texas.

Provisional Government of Oregon (May 2, 1843 – March 3, 1849)

The Provisional Government of Oregon was organized explicitly as a placeholder for a government until the United States would come in and take over. Its government was noteworthy for first having a Supreme Judge as the chief executive, Chairman of the Committee at Champoeg Meetings, then an executive committee, before finally settling on a governor. This was all set out in the Provisional Government’s constitution, the Organic Laws of Oregon. The loose government also acknowledged wheat, beaver skins, Mexican pesos and Peruvian reals alongside the United States dollar.

A private mint also minted so-called “Beaver Dollars” after the California Gold Rush kicked off in earnest. Some were concerned about the illegality of private mints under U.S. law, so the legislature appointed some of the board members, including the governor. When Oregon joined the Union, the San Francisco mint purchased Beaver Dollars at a premium and melted them down to make their own gold coins.

The Provisional Government’s laws were few, but they outlawed cruel and unusual punishment, the taking of property without compensation, unreasonable bail and distilled liquor. Somewhat famously, the law likewise barred entry to blacks, though the law against this was never actually enforced. Approximately 30 black settlers were counted by the captain of the USS Shark in 1846. In addition to being a “placeholder” for the United States, the Provisional Government also acted as a common defense system against natives.

The Oregon Treaty of June 15, 1846, ended the dispute between the United States and the United Kingdom over where the boundary between the United States and Canada lie. Two years later, the United States government created the Oregon Territory – where the entire legal code, save for Beaver Coins, was kept intact.

Republic of California (June 14, 1846 – July 9, 1846)

While California is one of the biggest states in the Union, its history as an independent republic is rather brief and fleeting – all told, the Bear Flag Republic lasted 25 days. While it claimed virtually all of the Mexican territory later incorporated into the United States outside of Texas, it realistically only exercised military control of an area around San Francisco. Still, while the history of the Republic proper is brief, the background leading to an independent (albeit, unrecognized) republic, is fascinating.

Alta California, as it was then known, was far from the population centers and centers of power in Mexico, and was widely neglected by the Mexican government. Leaders of the community openly discussed the option of independence or annexation by the United States, the United Kingdom or France. In practice, the region enjoyed broad autonomy. In 1845, the regional governor was rejected by an open revolt of the Californios. Political control of the region was further eroded by a feud between political Governor Pío Pico and Comandante José Castro.

Another complicating factor was the Mexican government’s policy of granting land to naturalized citizens. The process for naturalization was rather easy. In fact, Mexico encouraged the process. So large areas of land in California were held by citizens who were effectively Mexican in name only. In response, the Mexican government attempted to clamp down on the ability of foreigners to purchase land within Mexico without first obtaining naturalization.

Captain John C. Frémont, the first Republican nominee for president, was at that time a Brevet Captain in the Army. He has been variously accused of inciting the revolt, however, one thing is clear: the presence of a pro-expansion military officer certainly put wind in the sails of those wishing to officially throw off the Mexican yoke. Upon departing from a camp meeting with Frémont, Californian insurgency forces captured a herd of 170 Mexican military forces. They traveled from there to Sonoma, where they sought to capture the pueblo, which was the center of government power in Alta California. They found no resistance and quickly agreed to terms with the Comandante.

Unbeknownst to Los Osos (“The Bears,” so named both for their flag and their scruffy appearance), the United States and Mexico had been in a state of war for about a month. On July 7th, the United States Navy and Marine Corps arrived, raising the 27-star flag over Sonoma and the 28-star flag over Monterey. On August 17th, General Robert F. Stockton, head of the American forces in the Mexican-American War, announced a proclamation that Alta California was now part of the United States.

The original Bear Flag lasted until 1906, when it was destroyed in one of the fires resulting from the 1906 earthquake.

State of Deseret (1849 – 1850)

This one is slightly different than the rest on our list, but bears inclusion. It’s not an attempt at a separate country, but an unrecognized state organized by followers of the Latter-Day Saint Movement (Mormons) after their flight from Missouri. Initially, Church President Brigham Young planned to apply for status as a territory. However, upon hearing of California and New Mexico’s petitions for statehood, he instead changed his own petition for the same. They copied Iowa’s state constitution and sent it off to D.C.

Young and the Church mostly established their boundaries by wisely not asking for the already prime real estate. This meant Northern California’s Gold Rush country was out, as were the fertile farmlands of Northern Oregon. President Zachary Taylor, for his part, preferred the admission of the entire area of Deseret and California as a single state, which would also solve the problem of not admitting too many free states.

The Compromise of 1850 admitted the State of California and the Territory of Utah. The latter took up much of the northern half of the proposed State of Deseret. The demand for a “Mormon state” largely disappeared once the railroads brought an influx of non-Mormon residents to the region.

Republic of Sonora (October 15, 1853 – May 8, 1854)

Current Territory: The Mexican states of Baja California, Baja California Sur and Sonora

The annexation of Texas and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo put wind in the sails of those who sought to expand United States territory (and slave power) southward. The most radical of these movements were the Golden Circle, which sought for a breakaway Southern confederacy to control the entirety of the Caribbean through an invasion of Mexico, Central America and Spanish possessions. The slightly less radical All of Mexico Movement saw the entirety of Mexico as properly American soil.

This was the political climate that lead to the creation of the Republic of Sonora. American filibuster William Walker was the driving force behind the movement, which enjoyed its greatest popularity in San Francisco. He successfully sold “bonds” for the nation, which was anything but sovereign. He invaded Baja California and Sonora with 45 men, where he conquered La Paz, a sparsely populated area acting as the capital of Baja California. He then declared the Republic of Baja California, but later specified that this was simply one part of a larger Republic of Sonora.

Republic of Baja California (October 15, 1853 – January 1854)

Our story of William Walker picks up here. Neither the Mexican military nor the population were terribly keen on another Yanqui republic in their midst, so the opposition to Walker was stiff. On the other side of the border, while he found favor among a small number of committed radicals, this movement did not enjoy a wide base of popularity. Walker’s forces never controlled much territory outside of La Paz.

After continuous military defeat and defection by demoralized troops, Walker surrendered to the United States military in San Diego. He was put on trial for violating the Neutrality Act, which was part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The jury, operating at the peak of Manifest Destiny sentiment in the United States, took all of eight minutes to acquit him.

Modern Secessionist Movements in the United States

The separatist craze sweeping other parts of the Western world is not entirely absent from the United States. All told, there are 22 states with active movements to secede from that state to form a 51st. This is not without precedent: West Virginia was created out of Virginia largely due to political differences. Four of the above polities (California, Hawaii, Texas and Vermont) have active secessionist movements seeking to reestablish these defunct states.

As the United States becomes increasingly politically balkanized, don’t be surprised if it becomes geographically balkanized as well. You now know that there’s a long history of attempts to avoid central power in the United States.

America's Sovereign States: The Obscure History of How 10 Independent States Joined the U.S. was originally posted in the Resistance Library at Ammo.com.