"ROBINHOOD WILL HAVE TO BREAK INTO MY WIFE’S BOYFRIEND’S HOUSE IF THEY WANT TO FORCE ME TO SELL MY GME" - r/WallStreetBets meme.

An Inverse Of 1987

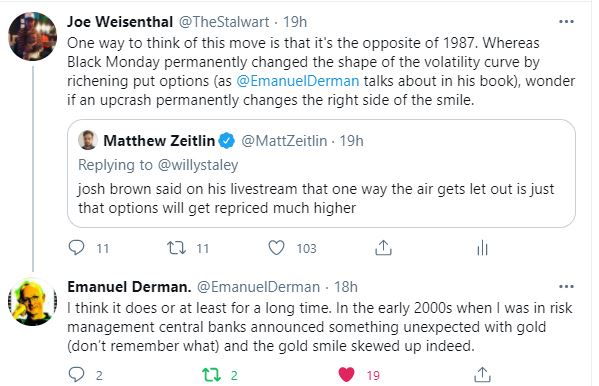

One of the more interesting takes on the GameStop (GME) saga last week came from Bloomberg's Joe Wiesenthal, drawing on the work of Emanuel Derman. For those unfamiliar with Derman, he was one of the first physicists to make the transition to quantitative finance in the '80s, moving from Bell Labs to Goldman Sachs (full disclosure: we've corresponded and met with Dr. Derman in the past, and he was kind enough to offer some feedback on our security selection algorithm).

Wiesenthal referred to Derman's memoir, My Life As A Quant.

In that book, Derman observed that after the 1987 crash, put options permanently became more expensive. Wiesenthal speculated on Twitter that in the wake of the GameStop melt-up, the same might happen to call options. Derman agreed.

More Expensive Calls, Less Expensive Collars

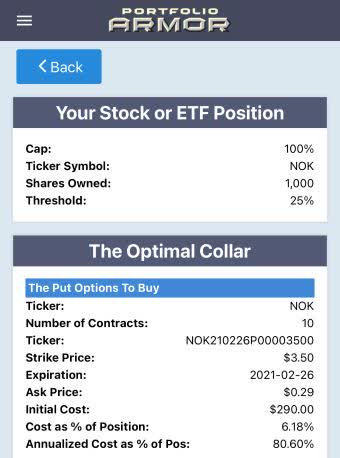

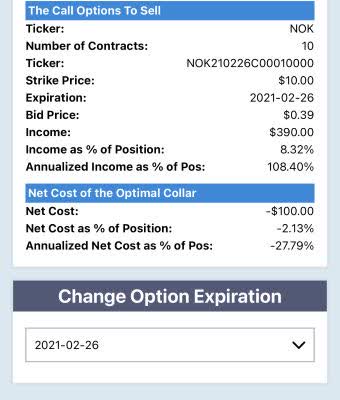

All else equal, more expensive calls would be good news for investors looking to hedge with collars. We haven't seen that with GameStop itself yet, but we did get a preview of it with one of the other meme stocks last week, Nokia (NOK). In our previous post (WallStreetBets Versus The Crackdown), we presented an extraordinary collar on Nokia:

A Hedged Bet On Nokia

Nokia offers an even better setup than BlackBerry did earlier this week in terms of upside potential versus downside risk. Let's say you picked up a 1,000 shares of NOK on the dip Thursday. This was the optimal collar, as of Thursday's close, to hedge your 1,000 shares of NOK against a >25% drop over the next month while capping your upside on the stock at 100%.

Screen capture via the Portfolio Armor iPhone app.

It's rare that you're able to cap a collar this high, which makes for the attractive risk-versus-reward setup here. Also, note the negative hedging cost.

That hedge was as of Thursday's close; using the same parameters, you could have found a similar optimal collar on Friday as well.

Still Too Risky For Some

For at least one reader, that Nokia hedge, with its 25% maximum downside, was too risky. Our regular commenter "propaganda4u" wrote,

Your worse case loss should never be more than 5%. Didn't you learn anything from William O'Neill?

William O'Neill, the founder of Investor's Business Daily, is of course known for his trading rules, including those regarding cutting losses. His rule is to sell when a stock drops 7%, not 5%.

My philosophy is that all stocks are bad. There are no good stocks unless they are going up in price, if they go down instead, you have to cut your losses fast. The key is to lose the least amount of money possible when you're wrong. I make it a rule to never lose more than 7% on any stock I buy. If a stock drops 7% below my purchase price, I will automatically sell it without any hesitation.

This rule does not limit your potential losses on a stock to 7% though. Stocks can gap down much further on bad news. It's not unheard of for a stock to open down 20% or more from its previous close after an earnings miss or other bad news. Here's an example of Snap (SNAP) doing that a few years ago (there are more recent examples, but this chart was handy).

If you had a stop order to sell this after it pulled back 7%, that wouldn't have helped you there. Hedging, unlike trading rules, can actually protect against drops of more than 7%, or more than 5%, if you're that risk averse.

Investing Without Risking A >5% Loss

The good news for our extremely risk averse readers such as "propaganda4u" is that it is possible to invest without risking a drop of more than 5%. Our system can construct hedged portfolios designed to maximize returns for investors only willing to risk a 5% decline.

The Tradeoff Of Risking Only A 5% Decline

The tradeoff is that hedging against such small declines narrows the universe of securities available. To quantify that, consider this. Our universe includes about 4,500 securities with options traded on them in the U.S. On Friday, 1,860 of them passed our initial screens and were hedgeable against >9% declines. Only 231 of those were hedgeable against declines of >5%.

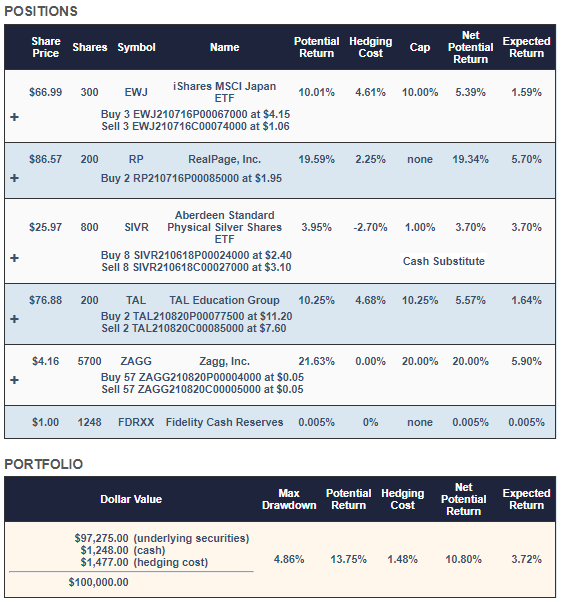

Whenever you ask our system to construct a hedged portfolio, it populates your portfolio with names that it estimates have the highest potential returns, net of hedging cost, out of the ones that fit your risk tolerance and portfolio size. If you indicated you were only willing to risk a decline of >5%, on Friday, it would have started with those 231 names that were hedgeable against a >5% decline. If you indicated that you had $100,000 to invest, our system would have filtered out names like Amazon (AMZN) that were hedgeable against >5% declines, but had share prices too high to fit a round lot in your portfolio. This is the hedged portfolio it would have presented you:

Screen capture via Portfolio Armor.

As you can see in the portfolio summary, the max drawdown there was a decline of 4.86%. That's how much the portfolio would be down if every security in it went to $0 just before the hedges expired.

Another Approach For The Risk Averse

Although the portfolio above limits your downside risk to a drop of 4.86% in the worst case scenario, its expected return over the next six months is fairly modest: 3.72%. Another approach for a risk averse investor would be to keep most of his money in cash and then take more risk in a hedged portfolio. For example, instead of investing 100% in a portfolio hedged against a >5% decline, invest 25% in a portfolio hedged against a >20% decline with the rest in cash. Our guess is that the second approach may do better. Let's check back in six months and see.