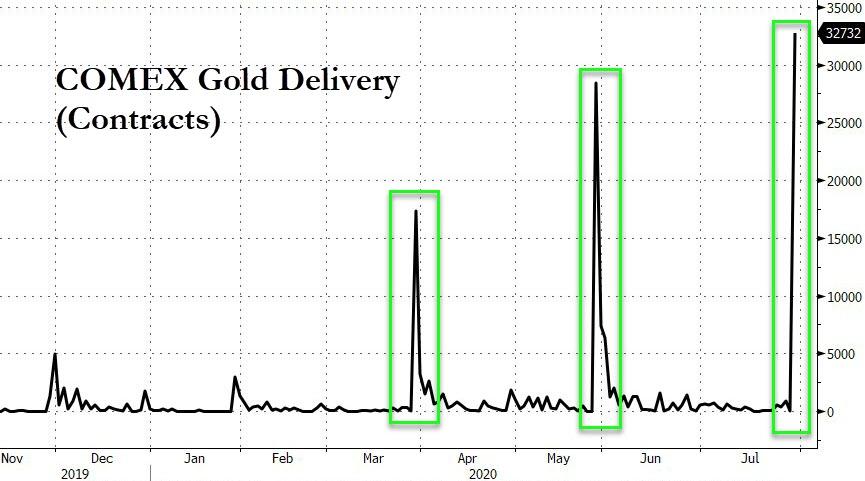

Traders on the main gold futures exchange in New York just issued the largest daily physical delivery notice on record.

In the latest sign of how the market's norms have been upended by the price disconnect that struck in March, Bloomberg reports that traders on Thursday declared their intent to deliver 3.27 million ounces (over 100 tonnes) of gold against the August Comex contract, the largest daily notice in bourse data going back to 1994...

Source: Bloomberg

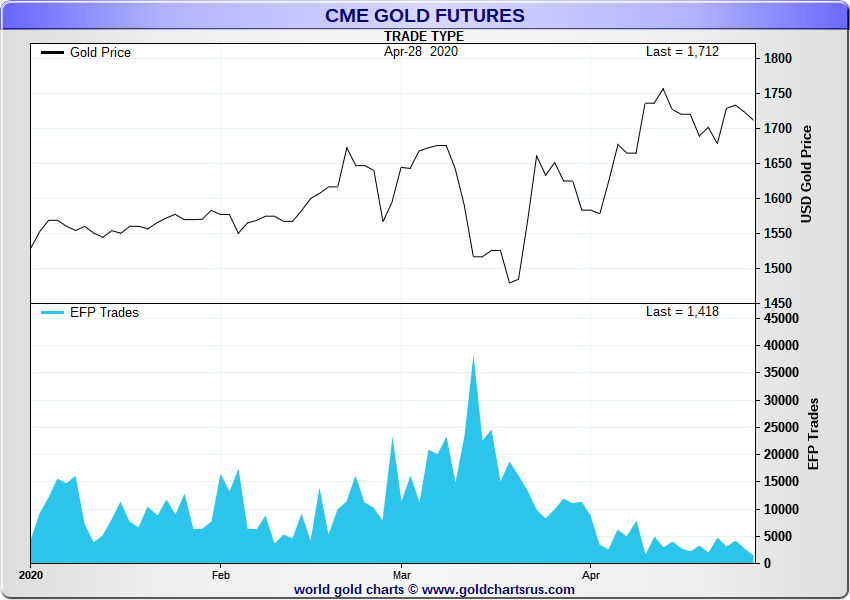

While millions of ounces of gold trade on the futures market every day, typically only a tiny fraction of that goes to delivery. But in recent months, huge amounts of bullion have flowed into New York and the COMEX has seen record deliveries.

Source: Bloomberg

As Jan Nieuwenhuijs of Voima Gold explains, three elements cause physical delivery on the COMEX to have reached record highs this year:

- strong demand for futures in New York,

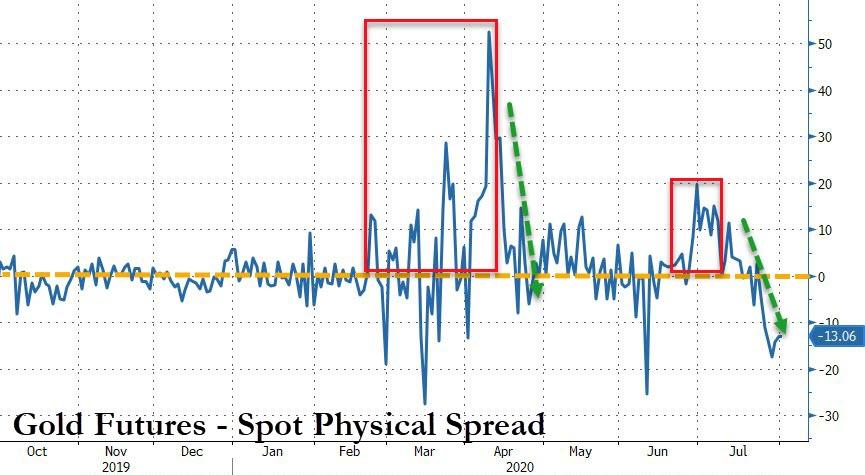

- a persisting spread between the price of futures in New York versus spot gold in London,

- and arbitrage.

Physical delivery on the largest gold futures exchange in the world, the COMEX in New York, has reached all time highs this year. Usually, delivery is “negligible.” What has changed?

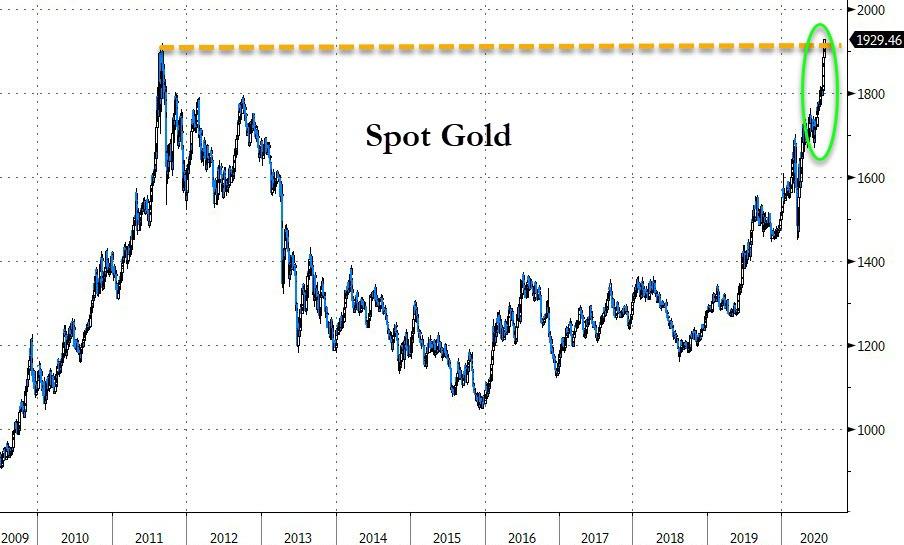

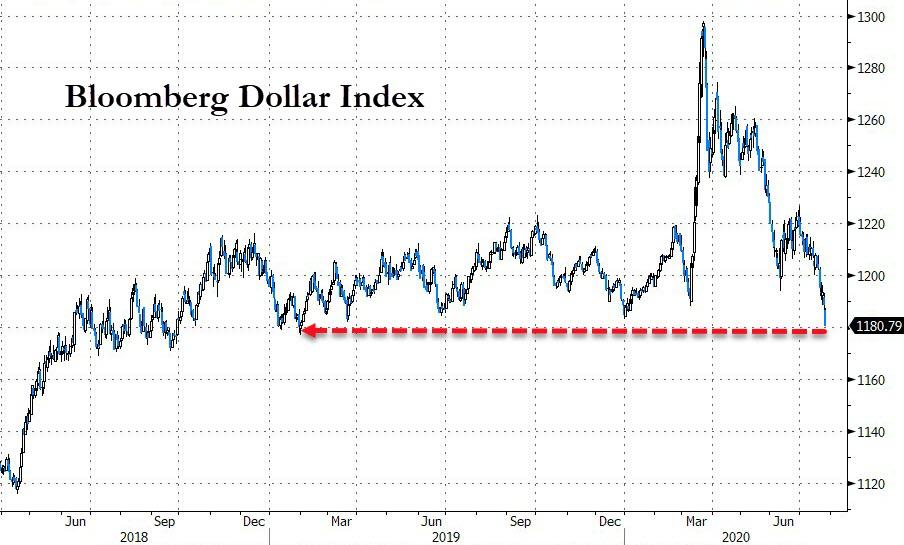

An important change in the global gold market occurred on March 23, 2020. On that day the price of gold futures in New York started drifting higher than the price for spot gold in London. Ever since, the spread has persisted, though it continuously widens and narrows. The reason for this disturbance in the market can be read in my previous article “What Caused the New York vs. London Gold Price Spread and Why it Persists.”

To understand the shift in deliveries, first let's have a look at how the global gold market operated before March 23, when things still ran smoothly.

The Global Gold Market Before March 23, 2020

The world’s most dominant gold spot market is the London Bullion Market, where mostly “loco London” gold is traded. Meaning the metal is physically settled within the environs of the M25 London Orbital Motorway. The most dominant gold futures market is located in New York, where metal can be physically delivered within a 150-mile radius of the City of New York.

Before March 23, the price in London (spot) and the price in New York (near month futures contract) always traded in tight lockstep because of arbitrage. If, for example, the futures price would trade above spot, arbitragers would “buy spot and sell futures” until the spread was closed. Arbitragers would hold their positions—long spot, short futures—until maturity of the futures contract, because at expiry the price of the futures contract was guaranteed to converge with the spot price. In this example we can see that strong demand in New York would be translated into spot buying in London.

Worth noting is that when a futures trader rolled its position into the next month, and his initial futures buying was translated into spot buying in London by an arbitrager, on a systemic level the arbitrager would roll its position as well.

Of course, the opposite happened as well. When futures traded below spot, arbitragers would “buy futures and sell spot” until the spread was closed.

So far, a simplified version of the market before March 23.

The Global Gold Market After March 23, 2020

Since March 23 of this year, futures have persistently been trading above spot, though the spread isn’t constant. As a result, arbitragers aren’t assured the futures price in New York will converge with the spot price in London. An arbitrage trade as described above, through a position in both markets, incurs risk.

What arbitragers currently do to profit from the spread is buy spot, sell futures, fly the metal to New York, and physically deliver the gold. This is how the profit is locked in. If the spread between spot and futures is $40 per ounce, the arbitrager’s profit is $40 minus costs for transport, insurance, storage, etc.

Now you can see why the persistent spread between New York and London has increased physical delivery on the COMEX through arbitrage.

Conclusion

Physical delivery on the COMEX is elevated because of the current unusual situation in the global gold market. The gold delivered in New York has been imported from spot markets such as Singapore, Switzerland and Australia. U.S. imports directly from the U.K. are rare, because in London 400-ounce bars are traded and the main futures contract in New York requires smaller bars for delivery.

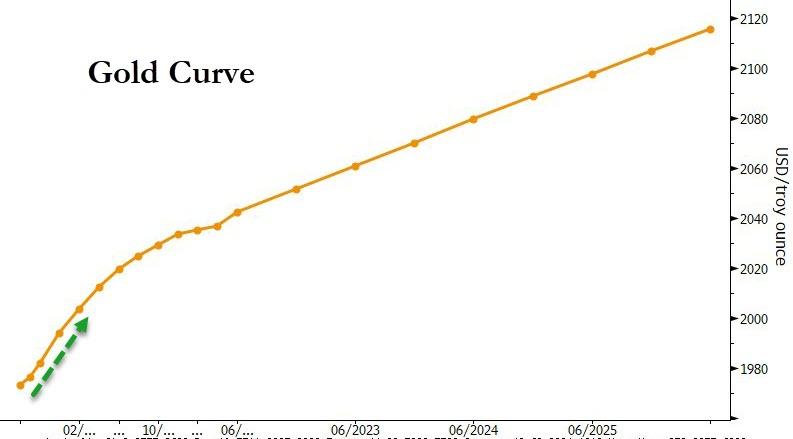

You might wonder who takes delivery from arbitragers that make delivery on the COMEX. Possibly, these are arbitragers, too. In the chart below you can see the spread between the “near month futures contract” and the “next near month futures contract.” This spread has also blown out on March 23. Arbitragers can buy the near month, and sell the next near month for a higher price. Subsequently, they take delivery of the near dated contract and make delivery of the further dated contract.

At the time of writing the near month (August) is trading at $1,973, while the most active month (December) trades at $1,994 dollars.

Arbitragers can buy long August and sell short December to collect $21 dollars per ounce.

One reason I can think of why the spreads persist, is because bullion banks are currently less active on the COMEX. Previously, bullion banks—having access to cheap funding—often performed the arbitrage trades.