We most recently described the Fed's stealthy plan to deposit digital dollars to "each American" during the next crisis as an unprecedented monetary overhaul, but more importantly, a truly stealthy one: there has barely been any media coverage of what may soon be a money transfer by the Fed - a direct stimulus to any and all Americans - bypassing the entire Legislative branch in an attempt to spark inflation after years of losing the war with deflation.

That's why two weeks ago we we delighted to read that none other than Jeff Gundlach's DoubleLine, one of the highest profile asset managers today, published a paper authored by fixed income portfolio manager Bill Campbell exposing what it called "The Pandora's Box of Central Bank Digital Currencies", in which it echoed our claims, writing that "such a mechanism could open veritable floodgates of liquidity into the consumer economy and accelerate the rate of inflation. While central banks have been trying without success to increase inflation for the past decade, the temptation to put CBDCs into effect might be very strong among policymakers. However, CBDCs would not only inject liquidity into the economy but also could accelerate the velocity of money. That one-two punch could bring about far more inflation than central bankers bargain for."

Alas, that was not enough to bring the topic of central bank digital currencies into the mainstream financial media, which is perhaps understandable for two reasons: i) everyone's attention is glued to the outcome and the implications of the election and ii) most media members think of CBDCs as some useless version of bitcoin, when nothing could be further from the truth.

So perhaps in hopes of attracting much needed attention to just how profound the monetary overhaul that is quietly taking place behind the scenes, Doubleline's resident digital currency expert, Bill Campbell has penned a follow up note to his original report, in which he explains in stark and vivid clarity what is about to happen. In a nutshell, "the world’s central banks and the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) envision a network of multiple cross-border payment systems featuring direct bilateral exchanges in the world’s different currencies. Such a regime would discard the decades-long mediation through the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. dollar." In short, central banks are preparing to launch cross-border payment systems which represent a new global order which poses a "major threat to the dollar and its status as the world’s reserve currency."

Below we republish the full note in whole due to its accurate and succinct assessment of how profoundly CBDCs will change the existing monetary architecture once they are launched in a few years (or earlier):

* * *

Bilateral Digital Currency Payments and the Twilight of the Dollar

by Bill Campbell, fixed income Portfolio Manager at DoubleLine (link)

If launched, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), as I have recently warned, will put at risk the independence of monetary policy and what little is left of fiscal discipline within their borders of circulation.1 Central banks are not stopping at the replacement of money as we have known it. In conjunction with their developmental work on digital currencies proper, monetary authorities are devising a new structure for electronic payments to sweep aside the decades-long framework for payment settlements, both domestic and international. The world’s central banks and the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) envision a network of multiple cross-border payment systems featuring direct bilateral exchanges in the world’s different currencies. Such a regime would discard the decades-long mediation through the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. dollar. This paper examines implementation plans for cross-border payment systems and the threat this new global order would pose to the dollar and its status as the world’s reserve currency.

King Dollar: A Brief History

The dollar has stood as the world’s reserve currency since taking that crown from the British pound in 1944. In July of that year, delegates from 44 nations met in Bretton Woods, N.H., convening the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, where they reached a series of agreements for the post-WWII international monetary system. The dollar formed the monetary linchpin of the new order. Participating nations pegged their currencies to the U.S. dollar and in exchange received the privilege to redeem dollars in gold from the U.S. (the world’s largest holder of gold reserves) at the congressionally set rate of $35 an ounce. This started a period of “exorbitant privilege” for the U.S., to quote former French Presidents Charles de Gaulle and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. Ever since then, thanks to the dollar’s reserve status, the U.S. can run a balance-of-payments deficit without the need to adjust domestic policy in order to settle its international trade bill. Because most international trade is transacted in dollars, which I explain in more detail below, in the most-extreme cases, the U.S. can print dollars to settle its balance of payment needs.2 All other nations must purchase dollars to fund their imports, and one way to attract foreign capital is with high real interest rates (interest rates above the domestic rate of inflation). On the margin, tighter monetary policy slows growth and compresses imports while attracting foreign capital. The U.S. doesn’t face that trade-off thanks to the dollar’s privileged status as the world’s reserve currency.

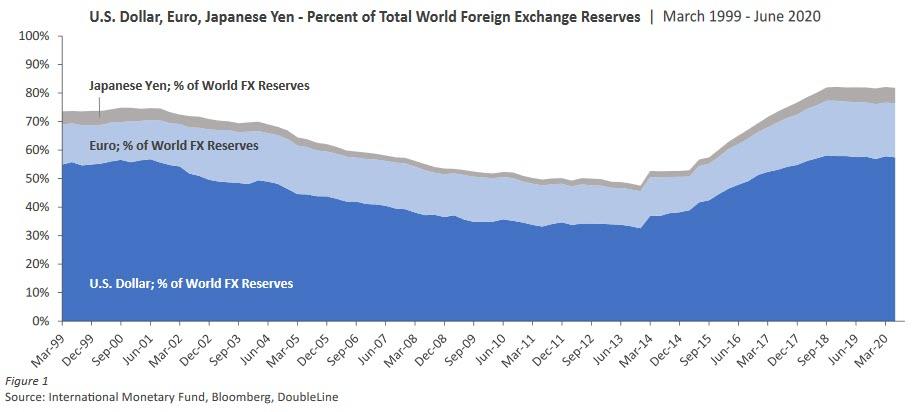

By the end of the 1960s, rising inflation and a surplus of overseas dollars had made dollar-gold convertibility unsustainable, and President Richard Nixon unilaterally canceled it on Aug. 15, 1971.3 The “closing of the gold window” effectively doomed the system of fixed currency exchange rates elaborated at Bretton Woods. By 1973, the regime of fixed exchange rates gave way to free-floating exchange rates. Despite de facto nullification of Bretton Woods, the U.S. dollar has remained unquestioned as the world’s reserve currency. Most of the world’s trade is transacted in dollars, with the majority of commodities traded in dollars. According to the International Monetary Fund, the dollar plays a dominant role in global invoicing. Through April 2020, the BIS reported, “The US dollar retained its dominant currency status, being on one side of 88% of all trades. The share of trades with the euro on one side expanded somewhat, to 32%.” The Japanese yen ranked third, with the currency being used on one side of 17% of all trades.4

The grumblings of French heads of state and other critics notwithstanding, a reserve currency is useful. (Figure 1) It facilitates global transactions, investments and international debt issuance, and interest payment and repayment by acting as a common denominator accepted by all countries. However, new conditions might be converging to depreciate the dollar in the forex markets and even one day topple its crown as the world’s reserve currency. In that event, the past of the British pound might not be prologue for the dollar. If central banking and the BIS dethrone King Dollar, I suspect no single currency will seize the crown of reserve currency. Instead, cross-border payments would be mediated by a conglomeration of bilateral arrangements.

Admittedly, for countries outside the U.S., such a system offers a very positive, even compelling feature: All countries would be able to settle their import bills in their own currencies, a privilege afforded predominantly to the United States and, to a lesser but noteworthy extent, the 19 countries constituting the eurozone and Japan. Even these countries, however, are obliged to settle payments for certain non-U.S. imports, notably oil and other commodities, in dollars.

SWIFT and Usurpers in the Wings

A key to the longevity of the dollar’s reign as the world’s reserve currency is its occupation as the principal medium of exchange by the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), the dominant provider of cross-border payment settlements. On May 3, 1973, which is to say, around the time fixed-rate forex regimes gave up the ghost, SWIFT was founded in Brussels with the support of 239 banks in 15 countries. Today, according to its website, the company connects more than 11,000 banks, securities organizations, market infrastructures and corporations in 200 countries. With the propagation of blockchain and cryptocurrency technologies, SWIFT faces fair and inevitable competition from new players in the private sector as well as older competitors in the business of the settlement of cross-border payment orders.5 SWIFT has been updating its infrastructure as well. In January 2017, the company rolled out its global payments innovation (gpi). In 2019, cross-border transfers via gpi exceeded $77 trillion, accounting for 56% of all cross-border payments for that year and 65% of SWIFT’s total cross-border payments, making gpi by far the most-used messaging system for international payment in the world.6

Whatever its resilience or vulnerability to private-sector challengers, SWIFT’s dominance faces a serious threat from outside the private sector – namely, the central banks, coordinated by the BIS. In a recently issued paper, the BIS and cosignatories, including the U.S. Federal Reserve Board of Governors and the European Central Bank, stated, “Central bank innovation is an opportunity for cooperation. Simultaneous research and exploration of CBDC by central banks could inform ways to improve cross-border payments.”7 The BIS has been spearheading research into “faster, cheaper, more transparent and more inclusive cross-border payment services [which] would deliver widespread benefits for citizens and economies worldwide, supporting economic growth, international trade, global development and financial inclusion.”8 The BIS has acknowledged that, despite technological advances in creating a new cross-border payments infrastructure, some of these central bank initiatives “are still in their design phase and others remain theoretical.”9 In a working paper published by the BIS, authors Raphel Auer, Giulio Cornelli and Jon Frost wrote, “Central banks are considering multiple technological options simultaneously, current proofs-of-concept tend to be based on distributed ledger technology (DLT) rather than a conventional technological infrastructure.”10 However, the landscape is quickly changing as more central banks scale up research into payment systems.

We have already started to see movement on these initiatives. China and Russia have already rolled out competing settlement systems to SWIFT, and both are looking into more bilateral settlement capabilities with their trading partners. In 2014, Russia implemented an alternative to SWIFT called the System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS). SPFS was seen as a response to the U.S. using its dominance in the global financial system to implement sanctions on Russia, its companies and individuals. In 2015, China launched its Cross-Border Interbank Payments System (CIPS). Stung like Moscow by U.S. financial sanctions, Beijing is encouraging its financial sector to make the switch from SWIFT. As more central banks work on their own settlement systems, Russia and China have shown that implementation can be a realistic goal.

“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

I foresee several big implications of the implementation of a new global payments system based on the bilateral regimes, all of which would put structural pressure on the dollar.

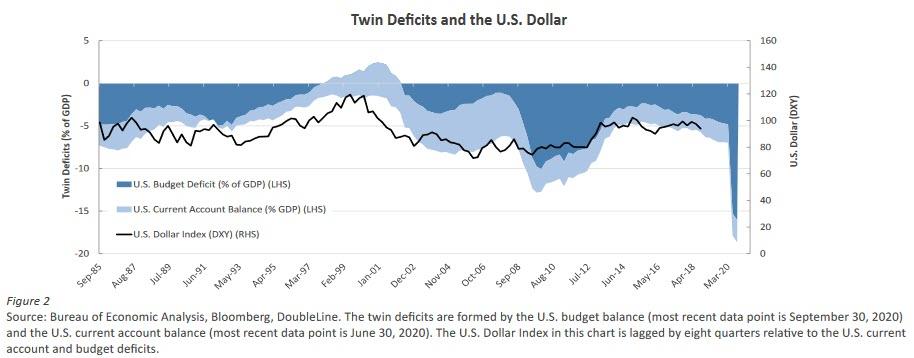

First, such a decentralized global payments system would take the world a big step toward removing the need for the dollar, or for that matter any other currency, to remain as the world’s reserve currency. Cross-border counterparties would settle payments in bilateral transactions in their own currencies, bypassing the dollar as an intermediary. The U.S. imports much more than it exports. These large current-account deficits create the need to have foreigners put their excess savings into U.S. assets to help stabilize the dollar. If foreign savings cease flowing into the U.S., the dollar will depreciate unless the import-export imbalance is corrected. (Figure 2)

Second, global central banks would no longer need to stockpile dollars and instead could diversify their foreign exchange (FX) reserves to a mix more commensurate with the countries with which they trade and conduct financial transactions. Dollar debt remains a large source of financing for many countries around the globe, but sovereign, corporate and other institutional borrowers have already begun to move some of this external financing into other denominations such as the euro and the yen.

Third, disintermediation of the dollar in cross-border payments could erode the greenback’s central role in pricing commodities and invoicing global trade. This would reduce a structural buyer of dollars. Outside the U.S., central banks have been forced to build up their dollar FX reserves in order to prevent a disorderly sell-off if exporters do not repatriate their dollar profits. In addition, in a reversal of norms in place since Bretton Woods, non-U.S. central banks might look to increase their holdings of gold relative to their dollar reserves.11 Central banks might increase the portion of their reserves allocated to gold, whose finite supply could help reduce debasement fears with respect to infinitely creatable CBDCs.

The End of a Single World Reserve Currency?

With the exception of two world wars in the first half of the 20th century, the world’s financial systems since 1815 have calibrated their international payments and banking reserves to a single reserve currency, first the British pound and the U.S. dollar since 1944. The nearly 80-year absence of viable alternatives has left Americans complacent about the dollar’s perpetuity as the world’s reserve currency. Outside the U.S., however, central banks and governments appear to foresee a future untethered from the dollar. The technology for such a delinking is here or soon will be. Central banks will possess the infrastructure to match their FX reserves to the currency mix and weightings of their balance of payments – and one day displace the dollar without the need to crown a new reserve currency.

Policymakers continue to steer intently into the uncharted waters of central bank digital currencies and decentralized global payment systems. Despite most of these initiatives still being in their theoretical design phase, global coordination among central banks will speed up their development and potential implementation. Armed with these currency and payment technologies, the world could rescind the exorbitant privilege the U.S. has enjoyed as printer of the world’s reserve currency and place structural pressure on the dollar to depreciate.

* * *

Citations:

1 Bill Campbell, “The Pandora’s Box of Central Bank Digital Currencies,” DoubleLine.com, Oct. 6, 2020. https://doubleline.com/dl/wp-content/uploads/The-Pandoras-Box-of-CB-Dig…

2 The balance of payments includes all transactions made between entities in one country and the rest of the world over a defined period of time.

3 “Foreigners’ liquid gold claims on US dollars increased tenfold from around $7 billion in 1953 to around $70 billion in 1971. Over the same period US gold reserves fell from over $22 billion to less than $11 billion. The inescapable decision facing the US authorities was taken on 15 August 1971 when the convertibility of the dollar at the fixed price of $35 per ounce of gold was ended,” Glyn Davies, A History of Money (4th edition: revised by Duncan Connors; 2016), pp. 465-466. University of Wales Press

4 Triennial Central Bank Survey, p. 3, Monetary and Economic Department, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Sept. 16, 2020. https://www.bis.org/statistics/rpfx19_fx.pdf

5 See, for example, Martin Arnold, “Ripple and Swift slug it out over cross-border payments,” Financial Times, June 5, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/631af8cc-47cc-11e8-8c77-ff51caedcde6

6 “SWIFT gpi Transferred Over $77T In 2019,” Global Payments, February 11, 2020. https://www.pymnts.com/news/international/global-payments/2020/swift-gp…

7 “Central bank digital currencies: foundational principles and core features,” Oct. 9, 2020, p. 3. Bank of Canada, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, Sveriges Riksbank, Swiss National Bank, Bank of England, Board of Governors Federal Reserve System and the Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/othp33.pdf

8 “Enhancing cross-border payments: building blocks of a global roadmap,” Committee on Payments and Market Structures, BIS, July 2020. https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d193.pdf

9 Ibid, page 4.

10 Raphael Auer, Giulio Cornelli and Jon Frost, “Rise of the central bank digital currencies: drivers, approaches and technologies,” BIS, August 2020, p. 5. https://www.bis.org/publ/work880.pdf

11 See Bill Campbell, “The Pandora’s Box of Central Bank Digital Currencies,” DoubleLine.com, Oct. 6, 2020. https://doubleline.com/dl/wp-content/uploads/The-Pandoras-Box-of-CB-Dig…