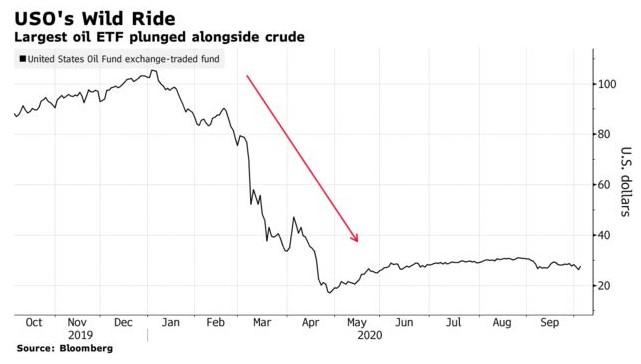

There appears to be a serious glitch in the market for options of exchange traded products. Unlike when an underlying stock splits and options adjust accordingly, when an ETP changes its strategy or rebalances - like the U.S. Oil Fund (USO) product did months ago, buying longer dated oil futures - options on that product do not adjust accordingly.

In fact, USO underwent several changes to try and save itself and respond to regulatory concerns when oil crashed. The fund survived, but those who bet on its demise were unfairly hurt on the trade. USO said it was just acting in accordance with its prospectus, which authorized the potential moves.

This type of impasse for options has cost holders "hundreds of millions of dollars", according Robert Whaley, the man who created the VIX index. He has been sounding the alarm on the "glitch" recently, as covered by Bloomberg.

And ETPs have adjusted their strategies more than usual in 2020, given the market's volatility.

Whaley thinks that the market and regulators simply haven't caught on yet. He told Bloomberg: “These things don’t occur that often, but at the same time they have occurred with increasing frequency in past months. I’m interested in issues of market integrity, and this is the antithesis to me.”

He continued:

“As they’re making these changes, what they’re doing is they’re reducing the volatility of a product. That reduces the value if you bought an option.”

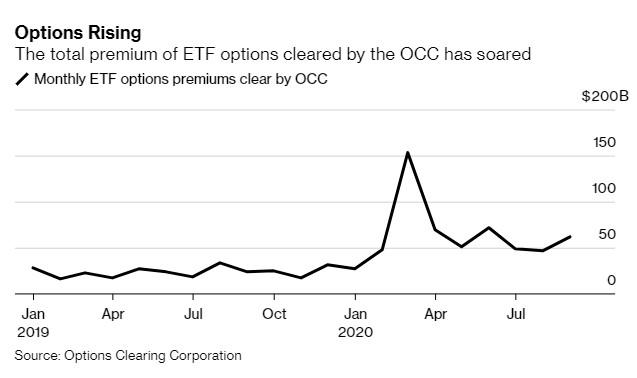

And while this would have been a smaller concern in years past, the market for ETP options has skyrocketed. $47 billion worth of ETF derivatives changed hands this past August alone, compared to $34 billion last year.

Whaley has now co-authored a paper that uses the volatility spike in February 2018 to demonstrate the issue. At the time, ProShares had reduced its leverage ratios in Ultra VIX Short-Term Futures fund (UVXY) and its Short VIX Short-Term Futures ETF (SVXY). The combined market value of options on the two names fell more than $116 million, Whaley predicts, as a result of the move.

These types of corporate events, not accounted for properly, result in “windfall transfers of wealth from outstanding long to outstanding short option holders,” Whaley concluded.