In an 8,000-word-plus tome, Ray Dalio, billionaire founder of Bridgewater - the world's largest hedge fund, took to LinkedIn to expand on his previous discussions about what happens next geostrategically, fearing economic tensions between the US and China escalating into armed conflict, drawing parallels between the current situation and the years before World War I and World War II.

"...the United States and China are now in an economic war that could conceivably evolve into a shooting war, and I've never experienced an economic war, I studied a number of past ones to learn what they are like," he wrote."Comparisons between the 1930s leading to World War II and today, especially with regard to economic sanctions, are especially interesting and helpful in considering what might be ahead," he added.

During times of great conflict, Dalio writes that there exists a tendency to move to "more autocratic leadership" to bring stability to chaos, concluding that rival powers only enter into wars when they are roughly comparable:

"Smart leaders typically only go into hot wars if there is no choice because the other side pushes them into the position of either fighting or losing by backing down. That is how World War II began."

With sanctions being swapped and the angry rhetoric rising, we suspect Dalio's warnings are more likely than ever.

* * *

The Big Cycle of the United States and the Dollar, Part 1

This is Part 1 of a two-part chapter on the US Empire and its path along the archetypical big cycle of dominant powers. It covers the period up through World War II. In Part 2, we will cover from the beginning of the new world order right up to this moment. It will be out on Tuesday, July 21.

To remind you, I did this study so that I could understand how we got to where we are and how to deal with the situations we are facing, but I am no great historian. I’m just a guy with a compulsion to understand how these things work and to bet on what will happen, who has access to great research assistants, fabulous data, incredibly informed experts, lots of insightful written research, and my own experiences. I’m using all of this to try to figure out what’s true and what to do about it. I am not ideological. I am mechanical. I look at reality as a perpetual-motion machine with cause/effect relationships driving developments through time. I am sharing this information with you to take or leave as you like and to have you point out any inaccuracies you think might exist as we try to figure out together what’s true and what to do about it.

This chapter is a continuation of the last chapter in which we started to look at each of the leading reserve currency empires over the last 500 years, starting with the Dutch and British empires.

...

As we delve into the particulars of the last 90 years, it is easy to lose sight of the big arcs, most importantly the three big cycles—i.e., the long-term debt/monetary cycle, the wealth and political gap cycle, and the global geopolitical cycle—as well as the eight major types of power and the 17 major drivers behind them. I will try to keep it simple, emphasizing just the most important developments in just the most influential countries, but if you find that the story starts getting more complicated than you’d like, remember that you can just read the text in bold in order to get the main points without complication.

World affairs and history are complicated because there is a lot going on both within and between relevant countries. Understanding just the most important relevant issues of just the most important countries is challenging because one has to see all of these perspectives accurately and simultaneously. All countries are living out their own stories that transpire on a daily basis, and these stories are woven together to make up the world story. But typically, at any one time, there are only a few leading countries and a limited number of major themes that make up the major story of the changing world order. Since the end of World War I, the most relevant stories have been those of Great Britain, the United States, Germany, Japan, the Soviet Union, and China. I’m not saying that these are the only countries that matter because that isn’t true. But I am saying that the story of the changing world order since World War I can be pretty well told by understanding the main developments within and between these countries. In this chapter I will attempt to briefly tell the stories of these countries and their most important interactions. This is the highlights version of the more complete version of the stories that I will pass to you in Part 2 of this book.

In telling these stories I will try to convey them without bias. I believe that to accurately understand both history and what is happening now, I need to see things through the relevant parties’ eyes, including those of enemies. While there are of course allies and enemies and it is tempting to demonize the enemies, most people and countries are simply pursuing their own interests in the ways they believe are best for them, so I find it productive to try to see things through their eyes and counterproductive to demonize them. If you hear me say things that sound sympathetic to former or existing enemies—like “Hitler built a strong economy before going to war”—please know that it is because I am seeking accuracy and need to be truthful rather than politically correct in conveying my thinking. While I might be wrong and we might not agree, that’s all OK with me as long as I am describing the picture as accurately as I can.

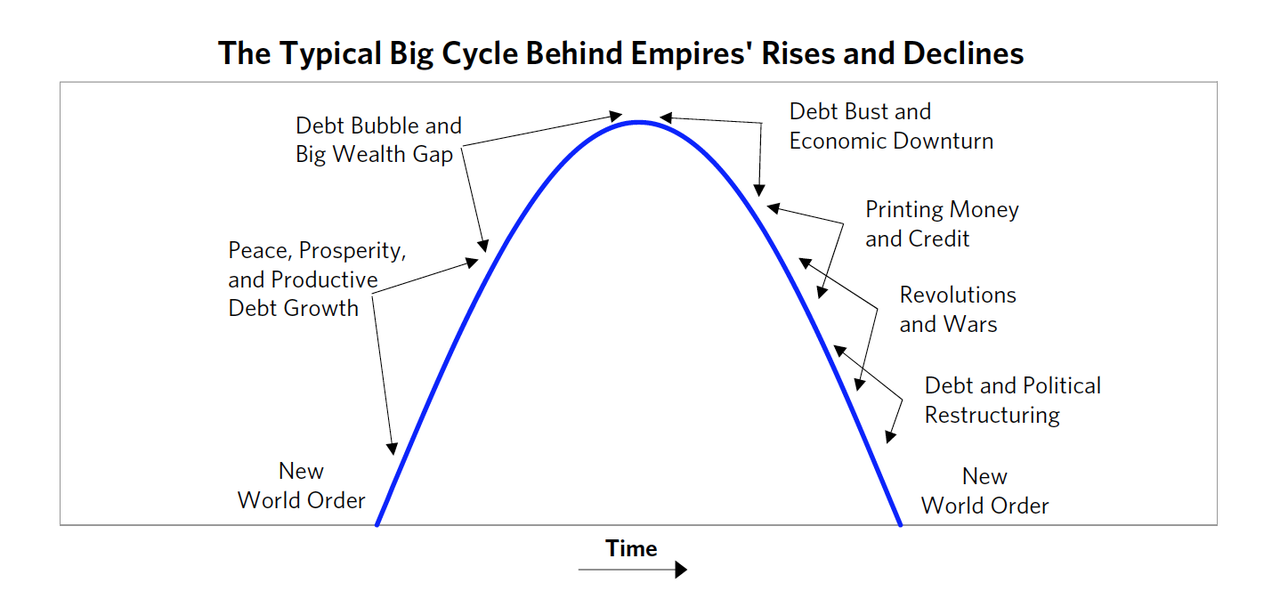

Before I begin recounting the story of the United States I’d like to remind you of the archetypical Big Cycle that I described earlier so you can keep it in mind as you read about how events transpired up to the present. Though a super-oversimplification of the whole thing, in a nutshell it appears to me that the archetypical Big Cycle transpires as follows.

A new world order typically begins after radical changes in how things work within countries (i.e., via some form of revolution) and between countries (typically some form of war). They change in big ways who has wealth and power and the approaches used to get wealth and power. For example in 1945, when the latest world order began, the US and its capitalist and democratic allies squared off against the communist and autocratic approaches of the Soviet Union and its allies. As we saw from studying the Dutch and British empires, capitalism was key to these countries’ successes but also contributed to their failures. It was successful because the pursuit of profit motivated people, and the competitive process of allocating capital and profit making directed resources relatively efficiently to what people wanted enough to pay for. In this system those who allocated efficiently profited, which led to them gaining more resources, while those who couldn’t allocate well died economically.

At the same time, this system of increasing wealth produced widening wealth and opportunity gaps, as well as decadence in the form of people working less and increasingly living on borrowed money. As the wealth and opportunity gaps grew, that produced increasingly widespread views that the system wasn’t fair. When the debt problems and other factors led to bad economic times at the same time as the wealth and values gaps were large, that produced a lot of internal conflict that led to large, revolutionary changes in who had wealth and power and the processes for getting them. Sometimes these big changes were made peacefully, and sometimes they were made violently. When the leading countries suffered from these internal challenges at the same time as rival countries had become strong enough to challenge them, the risks of external wars increased. When these seismic shifts in how wealth and power are distributed occur within countries (i.e., via revolutions) or between countries (typically through wars, though sometimes peacefully), the old world order breaks down and a new world order begins, and the process starts all over again.

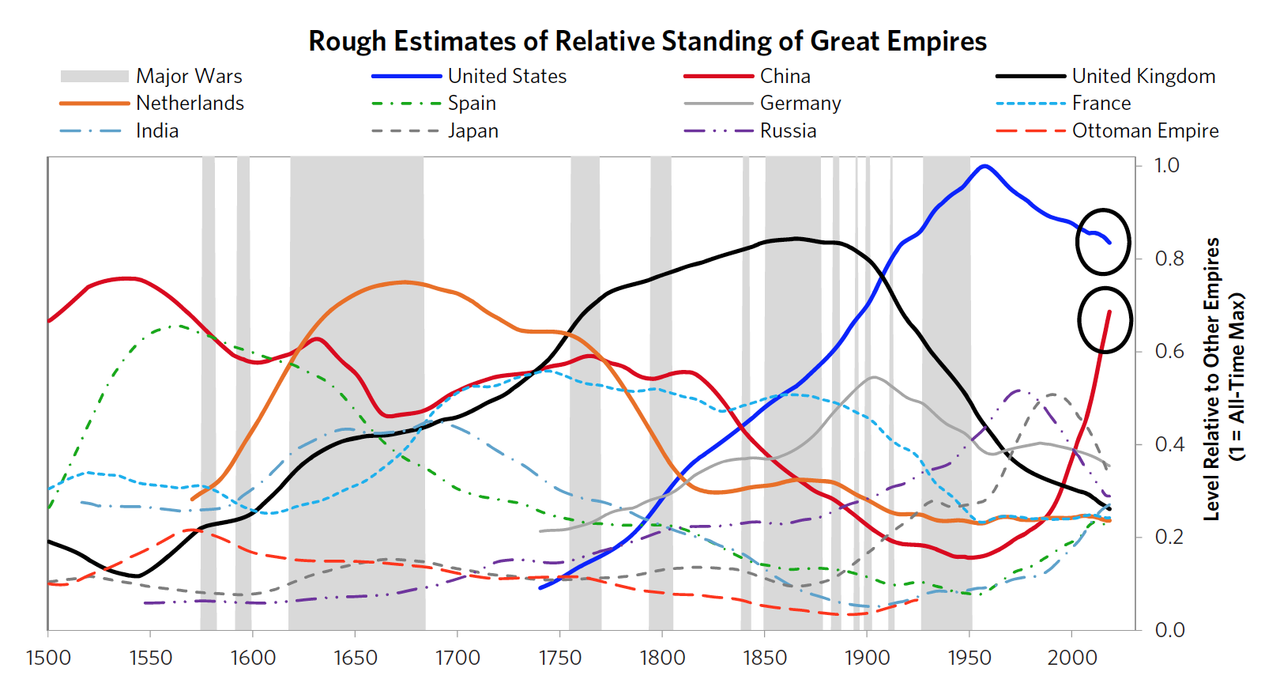

To refresh your memory, the chart below shows the relative powers of the leading countries as measured in indices that measure eight different types of power—education, competitiveness, innovation/technology, trade, economic output, military, financial center status, and reserve currency status.

In examining each country’s rise and decline I look at each of the eight measures and convey the highlights of their stories while diving into key moments to understand how they transpired in a more granular way. We will now do that with the United States and China, which as you can see in this chart are currently the leading powers.

The US Empire and the US Dollar

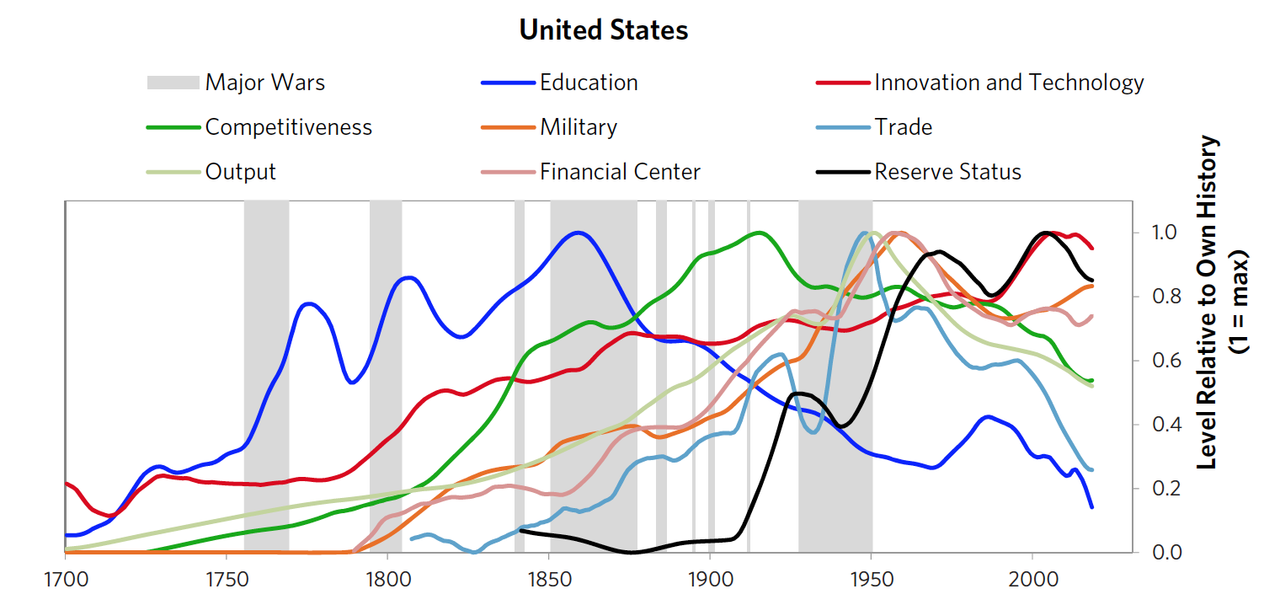

While this section primarily focuses on the story of the US since it overtook the British Empire as the dominant global power during the world wars, we will first take a quick look at the whole arc of its rise and its somewhat recent relative decline. The chart below shows the eight types of power that make up our overall measure of power. In it you can see the story behind the US’s rise and decline since 1700. We start in 1700 because that was just before the emergence of the United States. While the area now occupied by the United States was of course inhabited by native people for thousands of years, the history of the United States as a nation begins with the colonists, who revolted against the colonial power of Great Britain to gain independence in 1776. In the chart you can see the seeds of the US’s rise going back to the early 1800s, starting with rising strengths in education and then in innovation/technology and competitiveness.

These powers and world circumstances allowed the US to create massive productivity growth during the Second Industrial Revolution, which was from around 1870 to the beginning of World War I and then beyond it. These increased strengths were reflected in the US’s increasing shares of global economic output and world trade, as well as growing its financial strength, exemplified in New York becoming the world’s leading financial center, continuing leadership in innovations, and great usage of its financial products. You can see that these measures of the United States’ powers relative to its own history reached their peaks in the 1950s immediately after the Allies won World War II.

At that time, the gap between the US and the rest of the world was at its greatest and the US dollar and the US world order became dominant. Though the United States was clearly the dominant power in the post-World War II period, the Soviet Empire was a rival, though it was never nearly as strong overall. The Soviets and their communist satellite states vied against the much stronger US and US allies and satellite states until Soviet power began to fade under the weight of its growing inefficiency around 1980 and then collapsed in 1989-91. That is about when China began to rise to become a comparable rival power to the US where it is today.

As you can see, while the United States’ relative strengths of education, competitiveness, trade, and production have declined significantly and steadily over the last 100 years (to now be around the 50-60th percentile versus other leading powers), its relative strength in innovation and technology, reserve currency status, financial center power, and military have remained at or near the top. At the same time, as we will see when we delve into China’s picture, China has gained on the US in all these areas, has become comparable in many ways, and is advancing considerably faster than the US.

Let’s now drop down from the 40,000-foot level to the 20,000-foot level and pick up our story in 1930 so we can see how the United States evolved to become the dominant world power. While we focus predominantly on the US story, the linkages between economic conditions and political conditions within the United States and between the United States and other countries—most importantly with the UK, Germany, and Japan in the 1930s, with the Soviet Union and Japan from around 1950 until 1990, and with China from around 1980 until now—must be understood because economics and geopolitics within and between countries were and always are intertwined.

...

As a principle:

Protecting one’s wealth in times of war is difficult, as normal economic activities are curtailed, traditionally safe investments are not safe, capital mobility is limited, and high taxes are imposed when people and countries are fighting for their survival. During difficult times of conflict protecting the wealth of those who have wealth is not a priority relative to redistributing wealth to get it to where it is needed most.

That was the case in those war years.

While we won’t cover the actual battles and war moves, the headline is that the Allied victory in 1945 produced a tremendous shift of wealth and power.

World War II was an extremely costly war in lives and money. The numbers are gigantic and extremely imprecise. An estimated 40-75 million people were killed as a result of it, which was 3% of the world’s population, which made it the deadliest war yet. More than half of these losses were Russian (around 25 million) and Chinese (around 20 million). Germany lost around 7 million people—just over half were military deaths and the rest were German civilian deaths, mostly from the Holocaust (and millions more non-Germans were also victims). Britain and the United States each lost around 400,000. The financial cost of the war was both enormous and inestimable, according to most experts, but, based on my research, was in the vicinity of $4-7 trillion in current dollars. What we do know is that on a relative basis the US came out a big winner because the US sold and lent a lot before and during the war, basically all of the fighting took place off of US territory so the US wasn’t physically damaged, and US deaths were comparatively low in relation to those of most other major countries.

In Part 2 of this chapter, we will explore the new world order starting with the US as the dominant power and tell the story that brings us right up to this moment. Then we will turn to China.